[ad_1]

Spain is forging ahead with pension reforms that include a contentious fix for years of expensive promises to retirees: making younger people pay more.

While France is in revolt over plans to lift the minimum retirement age from 62 to 64, Spain’s threshold has been 65 for decades, leaving it searching for other ways to shore up a creaking pension system while being fair to young and old.

Having repealed 2013 reforms that had become politically intolerable for cutting the benefits of today’s retirees, Spain’s Socialist-led government will on Thursday ask lawmakers to approve a new package that demands more from younger generations.

José Luis Escrivá, Spain’s pensions minister, said the measures would move away from “the traditional paradigm of pension reform”, describing the French effort to raise the retirement age as an old-school approach.

Adopting measures eschewed by France, Spain will pull new money into the pensions pot from companies and employees — especially the highest-paid — then use it to reduce injustices such as the punitive impact of missed contributions on women who gave up jobs to look after children.

“We have created revenue-generating measures that will strengthen the system so that we can finance additional spending increases,” Escrivá told the Financial Times.

But there is controversy over one source of revenue called the “intergenerational equity mechanism”. Although its name hints at redistribution from older people to younger people, it in fact involves people in work having to contribute more to the social security system.

“Most experts think the title of this mechanism is perverse. It is just the opposite,” said Rafael Domenech, an economist at bank BBVA who advised on the repealed 2013 reforms, which were passed by a conservative People’s party (PP) government.

Escrivá disputes the characterisation. But Spain’s efforts exemplify the impossible dilemmas faced by many European countries: how to balance decent pensions for existing retirees, intergenerational fairness for young people, and financial sustainability.

Achieving two of these goals tends to be manageable. Securing all three is hard. Certain features of Spain make its challenge even tougher, starting with the urgency of reducing its public debt load, which is equal to 116 per cent of gross domestic product.

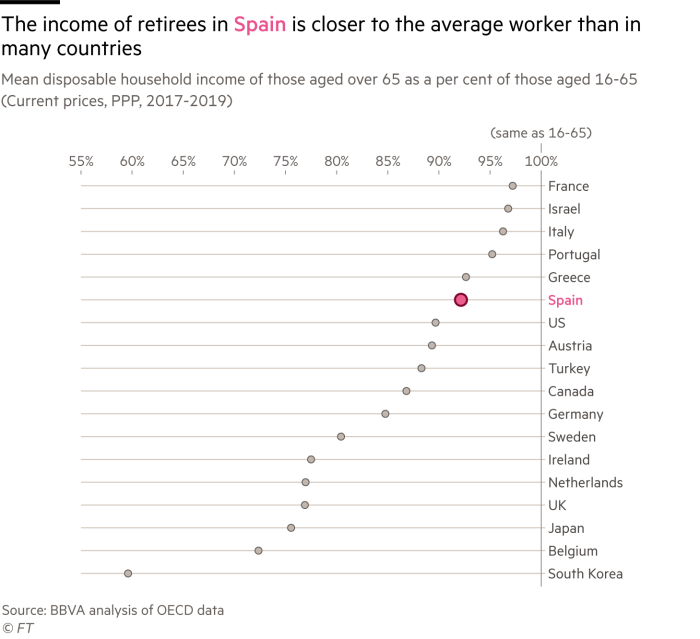

Another is that the country has not fostered a competitive market for 401k-style private pensions seen in the US or widespread employer-based plans. That means the elderly’s dependence on state pensions — with active workers financing the benefits of current retirees — is higher than elsewhere.

Partly for this reason, the benefits of existing pensioners are comparatively generous. The size of their pensions equates to 80 per cent of net pre-retirement income, ahead of France’s 74 per cent and an average of 62 per cent in the OECD club of countries.

The European Commission is pressing Spain to act. It has made a fairer and healthier pensions system a prerequisite for doling out billions of euros of EU recovery funds. The commission “positively assessed” the pension changes Spain made for previous payouts, but has yet to review the latest reforms.

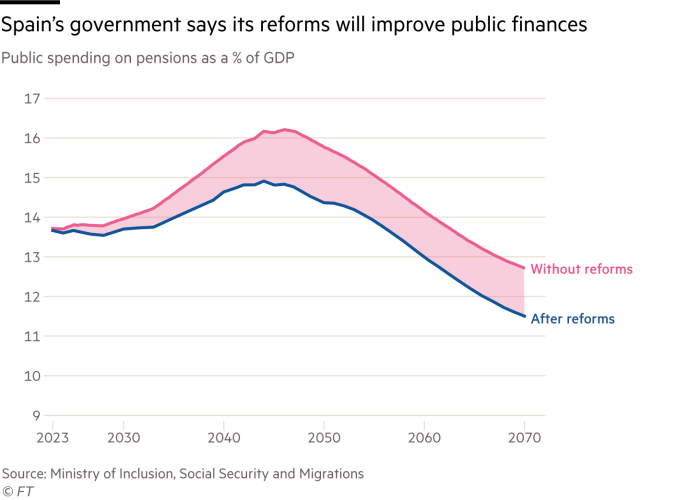

Airef, Spain’s independent fiscal watchdog, last week issued its judgment, saying the reforms in the round would not pay for themselves and would increase Spain’s budget deficit by 1.1 percentage points of GDP by 2050.

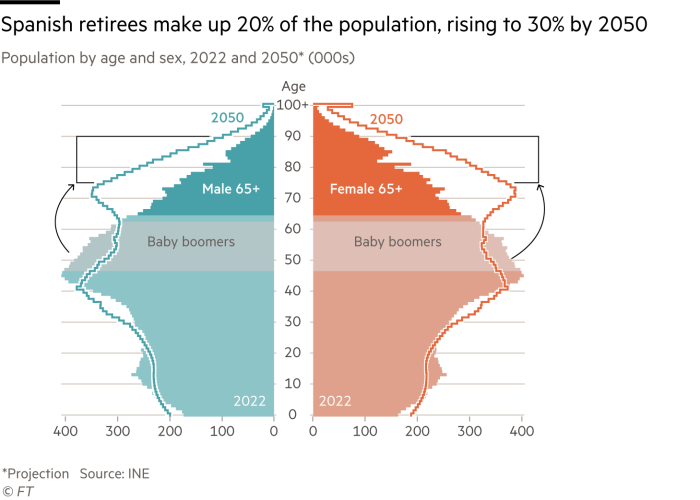

The demographic pressures are stark. Today in Spain there are three people of working age for every single pensioner; by 2050 that dependency ratio will be just 1.7 to one. The sharp drop is explained by Spain’s life expectancy of 83 — one of the world’s highest — and the fact its baby boom came late.

Although its civil war ended in 1939, Spain did not experience the surge in pregnancies that followed the end of the second world war elsewhere. Instead, the first years of Francisco Franco’s military dictatorship were marked by hunger, repression and international isolation. The birth rate did not climb until the economy began to take off in the late 1950s. Spain’s first baby boomers are just beginning to retire.

They are an irresistible force but politicians have given today’s pensioners an immovable promise, limiting their options for reform. In a letter to them last year, Escrivá wrote: “Whatever the circumstances, you must be sure that the purchasing power of your pension is always guaranteed.”

His sentiments reflected a consensus over the 2013 reforms on the political left. In order to limit costs, they had introduced mechanisms that would cap monthly pension payments when the system was in deficit and reduce benefits as the average lifespan increased.

These reforms had been due to come into force in 2019 but never did. As soon as it came to cutting the actual pensions of 10mn people who vote, the reforms became unacceptable to the Socialist-led government. Parliament voted to scrap them in 2021, although the PP opposed the decision.

That left Spain’s pensions linked simply to inflation. As a result, they rose 8.5 per cent in January, a better result than the average increase of roughly 3 per cent rise for salaried workers. The average payment is now €1,166 a month and the maximum €4,495.

“It’s not about being generous. It’s about making sure that pensioners have a dignified life,” said Fernando Luján, of the UGT union, which supports the latest reforms.

Opposed to them is the CEOE, Spain’s leading business lobby. It complains not only about employers having to make more social security contributions, one of President Emmanuel Macron’s main concerns in France. But the business group also highlights the raw deal for young people — already the main victims of high unemployment, low wages and insecure jobs.

Rosa Santos, labour relations director at the CEOE, described the intergenerational equity mechanism as a tax. Young people “are going to have to work more years in order to receive the same pension as current pensioners — and that’s in the best-case scenario, which is doubtful — having contributed much more to the system”, she said.

Sidestepping criticism about contributions, Escrivá argued that the reforms promote equity because “in relative terms the pensions of young people will improve more than those of older people”.

The government calculates that the reforms would add €5,300 to the pension of someone who is 60 today, but give a 25-year-old an extra €20,000.

As long as the benefits of current retirees are untouchable, it may be the best deal young people can get.

[ad_2]

Source link