[ad_1]

The current splash on the FT’s homepage is quite rightly on a fascinating new paper on “China as an international lender of last resort”, which details Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative debt problems.

The paper — written by Sebastian Horn of the World Bank; Brad Parks, a research professor at William & Mary; Harvard’s Carmen Reinhart; and Christoph Trebesch, a director at the Kiel Institute — explores both direct loans through state-controlled or state-owned banks and through swap lines with the Chinese central bank.

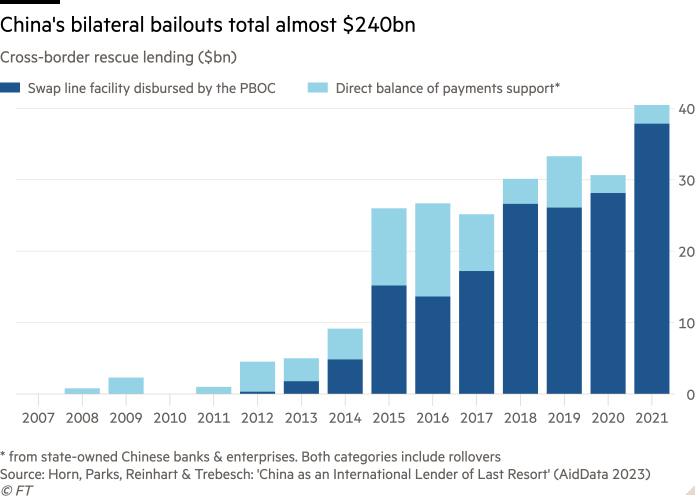

They found 128 bailout loans worth $240bn to 20 countries between 2000 and 2021. The vast majority ($185bn) was extended over the past five years of the study, and almost half happened in 2019-2021. Moreover, People’s Bank of China swap lines are far more meaningful than direct loans.

The paper (you can find the full thing here, and the data set here) argues that China has in practice “launched a new global system for cross-border rescue lending to countries in debt distress”, which has made the global financial system more opaque and fractured.

We build an encompassing new data set on China’s overseas bailouts between 2000 and 2021 and identify several new insights. Importantly, we find that the People’s Bank of China’s (PBOC) global swap line network has recently been used as a financial rescue mechanism, with more than USD 170 billion in emergency liquidity support to crisis countries. In addition, we document that Chinese state-owned banks and enterprises have extended an additional USD 70 billion in rescue loans for balance of payments support. In total, China’s overseas bailouts correspond to more than 20% of total IMF lending over the past decade and bailout amounts are growing fast. However, China’s rescue loans differ from those of established international lenders of last resort in that they (i) are opaque, (ii) carry relatively high interest rates, and (iii) are almost exclusively targeted to debtors of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Our results have implications for the international financial and monetary system, which is becoming more multipolar, less institutionalized, and less transparent.

In reality, the rescue loans are to a large extent actually a bailout for China’s banks, which have underpinned much of the estimated $838bn Belt and Road Initiative lending and have taken painful hits as a result. This probably helps partly explain why China has proven so difficult to deal with in many debt restructuring situations, such as Zambia and Sri Lanka.

The swaps are the most interesting aspect of the paper. Since 2008 the PBOC has set up swap lines with almost 40 overseas central banks. Officially their purpose was to promote the use of the renminbi for trade and investment purposes, and they long remained dormant.

However, that appears to be changing, with Argentina, Mongolia, Surname, Sri Lanka drawing them down shortly before or after sovereign debt defaults; and Pakistan, Egypt and Turkey doing so to ease balance of payments crises. FTAV’s emphasis below:

Our findings suggest, however, that the swap lines are increasingly used in situations of financial and macroeconomic distress, as they can help to bolster gross reserve holdings and address short-term liquidity needs. Out of 17 countries that have made PBOC swap line drawings thus far, only four did so in normal times, with no apparent signs of distress. Thus, a main insight is that China’s swap line network has become an increasingly important tool of overseas crisis management. In total, 170 billion USD have been extended by the PBOC to central banks of countries in financial or macroeconomic distress. This amount involves a large number of rollovers, as short-term PBOC swap loans are often extended again and again, resulting in a de facto maturity of more than three years, on average.

You can see the rising importance and usage of the swap lines in this FT chart recreated from the paper’s data:

The swap lines’ usefulness to countries in debt distress is complicated by whether China will allow them to be drawn and swapped for dollars, which is what most countries need to service their international debts or pay for imports.

In Argentina’s case this was known to have been granted, the paper notes, but without authorisation the swap might be of “limited use” in a classic balance of payments or debt crisis — with one important caveat.

The renminbi drawn down could be used to flatter a country’s gross foreign exchange reserves, but because they are short-term in theory they are typically not reported as debt. The swap lines can therefore be used as “window dressing” to make a country appear financially healthier than it really is.

The paper’s conclusions pulls no punches either:

We show that China’s role as international crisis manager has grown exponentially in recent years following its long boom in overseas lending. Its position is still far from rivaling that of the United States or the IMF, which are at the center of today’s international financial and monetary system. However, we see historical parallels to the era when the US started its rise as a global financial power, especially in the 1930s and after WW2, when it used the US Ex-Im Bank, the US Exchange Stabilization Fund and the Fed to provide rescue funds to countries with large liabilities to US banks and exporters. Over time, these ad hoc activities by the US developed into a tested system of global crisis management, a path that China may possibly pursue as well.

Our findings have major implications for the evolution of the international financial system, as cross-border rescue operations become less institutionalized, less transparent, and more piecemeal. China has demonstrated that a major creditor country (notwithstanding its current status as an emerging market) can create a large system of cross-border rescue lending to nearly two dozen recipient countries, while at the same time keeping its bailout operations largely out of public sight. Much more research is needed to measure the impacts of China’s rescue loans, in particular the large swap lines administered by the PBOC so as to gauge the full extent of debt distress in EMDEs and recalibrate what we understand as the global financial architecture.

There’s lots to think about here. FTAV will share its own thoughts soon, but yours go in the comments below.

[ad_2]

Source link