[ad_1]

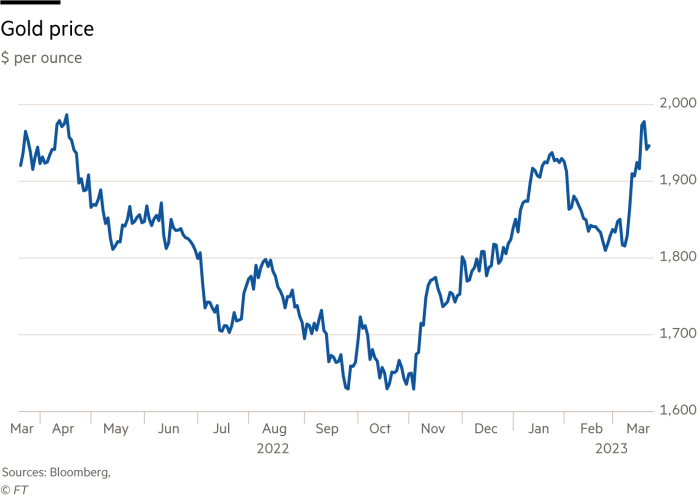

Traders quip that one of the few things to rally during bear periods is volatility. Add gold to the list. Its price has leapt about 7 per cent so far in March to one-year highs of just under $2,000 per ounce. With investors dumping stocks and corporate bonds, money has flowed into both government bonds and gold.

Interest in the yellow metal seems odd, given that price inflation in the US and elsewhere may well have peaked. And gold offers no income to investors, only capital gains and losses. In physical form, its storage presents problem. So what explains the renewal of interest?

Well, gold does offer a safe haven, particularly for retail investors worried that their money may not be safe in a bank. Bars, coins and jewellery make up the bulk of gold demand, about 72 per cent last year. Those proportions have changed little in years.

Over the past year or so, a key source of demand has been central bank buying. Between 2020 and 2022 central bank purchases went up 4.5 times. In the final quarter of 2022 the leading buyers were China and Turkey.

Countries such as China, the world’s largest producer of gold, Russia and Turkey have aimed to bolster their foreign exchange reserves. But they also have a desire to diversify from any dependency on the world’s most popular reserve currency, the US dollar.

Investment flows into physical gold exchange traded funds can swing prices short term. These ETFs are pooled open-ended investment funds divided into easily traded, often low-cost units. Recently, inflows into these ETFs jumped to their highest weekly level since March last year at 21.4mn tonnes. Almost all of that was in North America, according to World Gold Council data.

Gold appears to have attracted buyers precisely because inflation may decelerate and global economic growth could slow. That should mean currently high real interest rates — those adjusted for inflation — will start falling. Bulls believe positive real rates kill off demand for gold, not to mention inflation itself.

This month, two-year real US Treasury yields have dropped below 1.4 per cent, the lowest in six months. That trajectory hints that US interest rates may have peaked for this year at least. That would also begin to take some pressure off any indebted companies borrowing in dollars, at the very least.

Higher gold prices is good news for mining bankers. A spurt in gold prices late last year triggered dealmaking. In December, Agnico Eagle and Pan American gazumped South Africa’s Gold Fields to buy Canadian gold producer Yamana for $4.8bn. In February, US gold miner Newmont confirmed its interest in a $17bn bid for smaller Australian rival Newcrest.

More deals should follow if gold prices continue ascending. With central banks, especially the Fed, likely to reconsider the trajectory of rate increases, gold’s price should remain well bid this year.

Maserati: tuning needed for listings race

Can you hear a faint roar in the distance? It might be the sound of Maserati heading to the public markets. The Italian luxury sports car maker is still miles from that destination. But it is already a separate business within carmaker Stellantis.

With Porsche up almost 40 per cent since its float last year and Ferrari’s valuation thundering ahead, the market is starting to do a spot of window shopping.

Caution applies to investment in charismatic businesses such as luxury carmakers and football clubs. It is easy to get carried away. Lex once valued Aston Martin Lagonda shares at £10. They are now worth just over £2.

We have therefore subjected Maserati to sceptical analysis well before any IPO and the breathless marketing that goes with that.

Maserati is midway through a strategic U-turn. It is seeking to focus on profits rather than sales. It has spruced up its range, adding the MC20 model with a £200,000 price tag. Revenues are growing again after a few tricky years, up 15 per cent in 2022 to €2.3bn.

Operating profit margins have also recovered, to 8.7 per cent in 2022. It is targeting 15 per cent by 2024 and 20 per cent longer term. No listing is likely before then.

Today, Maserati is miles behind Porsche and Ferrari. The average selling price of its cars is less than €100,000, according to Bernstein analysis — not that different from pricier Mercedes or BMW cars. Ferraris can cost €500,000 or more. Porsche — whose models run a wide gamut — has higher volumes to lend a helping hand.

Maserati may find it difficult to go head to head with super sports car brands. But it is charting a different route. Maserati has pledged to bring out an electric version of all its models by 2025, and to go entirely electric by 2030. That is a canny move. It should help Maserati attract a different type of customer, not least among eco-conscious tech entrepreneurs.

How much might Maserati be worth? On today’s paltry margin, it would not deserve much of a premium to the likes of BMW. The enterprise value of the latter — which totals market capitalisation and net debt — is around one times last year’s sales. But the group does have room to raise profitability as it focuses on pricier models. If one — generously — applied Porsche’s valuation of 2.6 times last year’s sales, that would raise Maserati’s enterprise value to €6bn.

Of course, the market would need to see continued evidence of a well-executed turnround before it gave the carmaker anything like that sort of accolade. Stellantis is right to keep Maserati in the garage until its engines are firing on all cylinders again.

Lex is the FT’s concise daily investment column. Expert writers in four global financial centres provide informed, timely opinions on capital trends and big businesses. Click to explore

[ad_2]

Source link