[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

This morning, the financial community woke up in a world where Credit Suisse has been snuffed out.

All financial institutions have good years and bad years. But what mattered to Credit Suisse was beating UBS. Now, to be acquired by your rival, it must be a big shock to those at both banks. It is a tectonic shift for Switzerland’s storied banking culture and, more broadly, for global finance.

I will say, in my interactions with Credit Suisse’s people — especially in Washington — they were polite, friendly and willing to explain things. I would not say that about all the global banks.

In the US, which remains roiled in its own banking crisis, the focus is on regional banks and their ability to withstand the contagion from Silicon Valley Bank. Community banks play a big role in funding commercial real estate and if the banks pull back lending, how will that affect support for the Inflation Reduction Act? Will a credit squeeze now detail the IRA? This is a concern we will be following.

We would also like to highlight our colleagues’ report at the end of last week about the responses to the EU’s proposals to boost renewable manufacturing. European solar companies complained limits on Chinese imports could stymie their own production. At least one wind energy business said the measures won’t work until they are backed up with hard cash.

In today’s newsletter, Kenza investigates the continued strength of the “greenium” in the sustainable bond market. And Tamami delves into big questions about the Bank of Japan’s climate considerations now that the central bank is under new leadership — Patrick Temple-West

Green flavours trump plain vanilla

In the debt markets, green sells. Bonds with sustainability labels of any kind outperformed “vanilla” equivalents in the second half of last year, according to new research, adding to evidence this type of debt can nudge up returns for fixed income funds.

Analysis of 72 euro and dollar-denominated corporate bonds by the non-profit Climate Bonds Initiative found every flavour of sustainable debt outperformed other debt issued by the same companies in the second half of last year.

This included so-called sustainability-linked bonds, which penalise issuers who fail to meet certain environmental and social goals, and more traditional “use-of-proceeds” bonds which earmark cash raised for projects such as solar panels or assisted housing.

“Thematic bonds have issuers and investors head over heels for one another,” said Sean Kidney, CBI’s chief executive. “In a crucial decade for climate action, the sustainable bond market is the goose that laid the golden egg.”

Debt with a green label had the highest boost, known as a “greenium”: yields averaged close to half a percentage point lower compared with equivalent bonds, according to the CBI. (Bond yields fall as prices rise.) This means companies raised their money more cheaply than they otherwise would have done.

It also found evidence of higher price rises in secondary markets in the month following issuance, which would have benefited investors.

German government bonds are often used to illustrate the pricing benefits of green bonds, as the country issues green and non-green debt simultaneously in an easy-to-compare “twin” structure. The average yield on a €5bn German government issuance with a green tag was 1.25 basis points lower than its plain equivalent last August, the CBI said.

However, critics point out that in the absence of strong regulatory scrutiny, any issuer can decide to add a green tag to a bond, albeit not without controversy in the case of big polluters like airlines or oil majors. It must simply promise to spend the money it raises on projects with biodiversity or climate benefits.

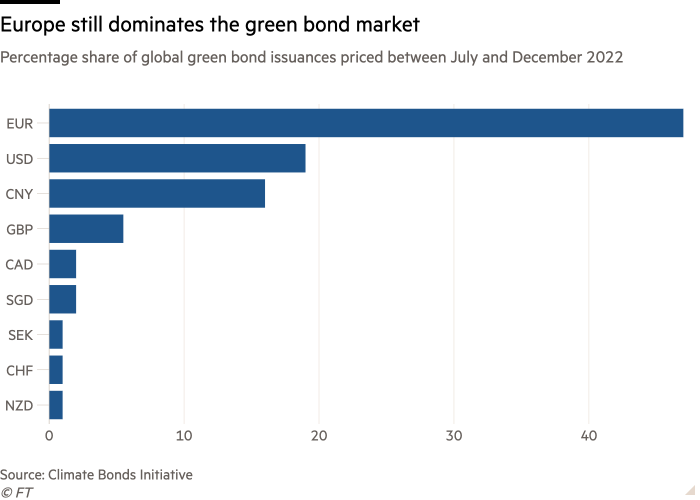

As bond markets tanked around the world last year and retail awareness of the potential for greenwashing grew, issuances in the sustainable bond market fell for the first time ever, from $1.1tn in 2021 to $863bn in 2022, according to Bloomberg data.

Even so, several investors told the CBI they would not have bought some bonds if it were not for the green label attached, including those issued by car companies Renault and Volkswagen. (Kenza Bryan)

Questions about climate risk abound under new BoJ leadership

After Haruhiko Kuroda led the Bank of Japan through 10 years of “unprecedented” monetary easing, Kazuo Ueda is set to become the next Bank of Japan governor on April 9.

The first task Ueda will face will be to normalise Kuroda’s ultra-loose monetary policy — without causing huge side-effects on the world’s third-largest economy. But ESG-conscious investors might have another question: how will Ueda handle Kuroda’s climate change legacy?

Kuroda made clear his belief that helping society tackle climate change is within the central bank’s mandate. Under his watch, the BoJ launched a scheme that offered zero-interest loans to banks to boost green and transition finance.

Ueda, who will become the first BoJ chief from academia in postwar Japan, has made very few comments on the topic of using monetary policy to respond to the risks of climate change. A rare example is Nikkei’s article published in December 2021 (available here for any Japanese-speaking readers.)

In the article, Ueda argued that while central banks can address the risks of climate change, the action should be temporal and proceed with extra care. Guiding markets and societies to decarbonise is more of a job for fiscal authorities, as the central banks don’t have enough tools to do so, he added.

He also said that establishing carbon tax and carbon pricing schemes, which he believed would trigger innovations in the field of clean energy, is more of “a natural way” to achieve a net zero society than interventions by central banks. If businesses cannot raise enough money for green transformation and need public support, “financial institutions which are close to the governments” — rather than the central banks — should step in, he wrote.

His scepticism towards the central bank’s role in mitigating climate change shows a stark contrast from a former candidate to lead the BoJ. Masayoshi Amamiya, a BoJ veteran whom Nikkei reported had been approached as a possible successor to Kuroda, believed that responding to climate change was an important part of the BoJ’s mandate.

With Ueda’s apparent reluctance to deepening the central bank’s involvement in the fight against climate change, many BoJ watchers don’t expect further commitments in this area.

But on the other hand, very few expect Ueda will introduce drastic changes compared with his predecessor. As Fumio Kishida’s administration sets green transformation as one of its top priorities, it’s unlikely that Ueda will unwind Kuroda’s initiatives, said Satoru Kado, principal economist at Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting. (Tamami Shimizuishi, Nikkei)

Smart read

Companies that back off their social and environmental commitments in the face of “nonsense” political attacks risk alienating a generation of talent, Mars’s new chief executive has warned. In his first interview since becoming CEO last September, Poul Weihrauch told our colleague Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson that “quality companies are deeply invested in [ESG] and if I walk out of this office and I take a 25-year-old associate that has joined us from university they will want us to do this”.

“We don’t believe that purpose and profit are enemies,” he added.

[ad_2]

Source link