[ad_1]

Investors are betting the European Central Bank will raise interest rates to all-time highs, spurred on by the eurozone economy’s resilience and signs that inflation could prove tougher to rein in than expected.

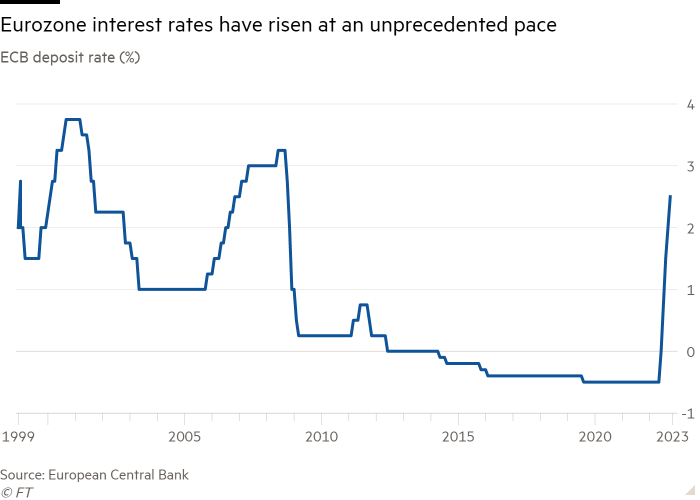

The Frankfurt-based central bank, widely seen as one of the world’s most dovish during its eight-year experiment with negative borrowing costs, is now expected to raise rates substantially this year.

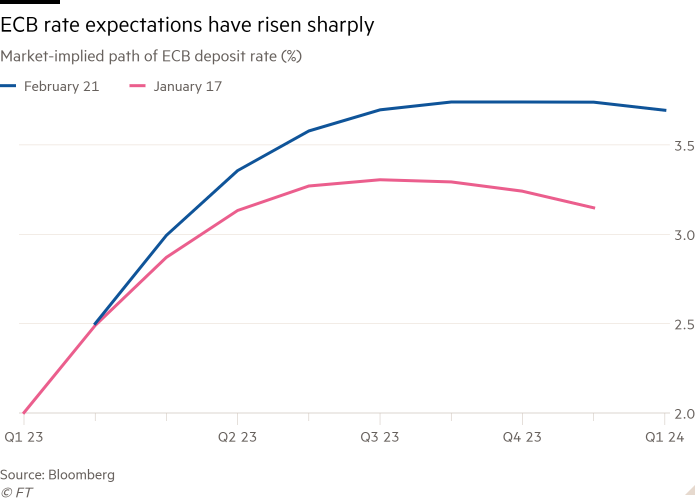

Swap markets are pricing in a jump in the ECB’s deposit rate to 3.75 per cent by September, up from the current 2.5 per cent. That would match the benchmark’s 2001 peak, when the ECB was still trying to shore up the value of the newly launched euro.

“It is really surprising to see the ECB now looking like the most hawkish of the big central banks,” said Sandra Phlippen, chief economist at Dutch bank ABN Amro.

Markets have revised forecasts of interest rates upwards after recent eurozone data on buoyant service-sector activity and wage demands.

ECB president Christine Lagarde said on Tuesday that the bank was “looking at wages and negotiated wages very, very closely” — an indication of concern a sharp rise in salaries this year will maintain pressure on prices as companies pass costs on to consumers.

The yield of German two-year bonds, which are highly sensitive to changes in interest rate expectations, hit a 14-year high of 2.95 per cent on Tuesday after the S&P Global purchasing managers’ index outstripped forecasts.

The prospect of further substantial rate rises in the eurozone contrasts with the US and the UK, which are widely considered to be closer to the end of their interest rate rise cycles, having already increased borrowing costs earlier and by more than the ECB.

However, US stock markets fell sharply on Tuesday as upbeat economic data prompted investors to re-evaluate how much further the Federal Reserve may raise rates.

Eurozone inflation of 8.5 per cent in January compares with 6.4 per cent in the US. While UK inflation remains in double digits, it has fallen faster than expected and the country’s anaemic growth outlook has diminished pressure on the Bank of England to increase rates.

In the past week, Goldman Sachs, Barclays and Berenberg have raised to 3.5 per cent their forecasts for how much further the ECB will raise rates.

“There is a risk that inflation proves to be more persistent than is currently priced by financial markets,” Isabel Schnabel, an ECB executive board member, told Bloomberg this week.

Frederik Ducrozet, head of macroeconomic research at Pictet Wealth Management, forecast ECB rates would peak at 3.5 per cent but added the central bank could “still be in tightening mode by September and that takes you close to a deposit rate of 4 per cent”.

The ECB has already raised rates by an unprecedented 3 percentage points since last summer and this month signalled plans for another half percentage point move in March.

Wages in the 20-country bloc have been growing at close to 5 per cent in recent months, according to a tracker published by the Irish central bank and jobs website Indeed.

Unions are responding to last year’s record inflation by demanding even higher pay rises. FNV, the biggest Dutch union, is calling for a 16.9 per cent pay rise for transport workers, while Germany’s Verdi union wants 10 per cent pay rises for 2.5mn public sector workers.

Although eurozone inflation has fallen for three consecutive months, core inflation — stripping out energy and food prices to show underlying price pressures — was unchanged at a record 5.2 per cent in January.

“The performance of the economy is obviously good news in the short term for the eurozone, but for the ECB . . . it could suggest they may have more work to do on policy rates,” said Konstantin Veit, portfolio manager at bond investor Pimco. He added that the ECB had made clear that inflation fighting was its “absolute top priority”.

Ducrozet at Pictet added: “Even the most moderate doves [in the ECB] are talking about a series of rate rises and not stopping anytime soon.”

Resilient economic data across advanced economies this month has led economists and financial experts to bet that interest rates will stay higher for longer than they previously considered.

“There has been a repricing in major developed rates markets,” said Silvia Ardagna, an economist at UK bank Barclays. “The fact that US core inflation was a bit stronger than expected last month has made everyone think that maybe it hasn’t peaked yet.”

[ad_2]

Source link