[ad_1]

When Peter Rochford, managing director of commercial cleaning company CleanTEC, was thinking about succession planning for the business he founded two decades ago, he had not even heard of employee ownership trusts.

“Trade sales are the norm in the industry,” he says, but he and his business partner Chris Rogers were reluctant to have the business swallowed up by a rival and put the jobs of staff at risk.

“It wasn’t just me and my co-founder that drove the business forward, it was the staff too — so a recognition for them and to protect their jobs was a strong factor as to why we went down the employee ownership trust route,” he says.

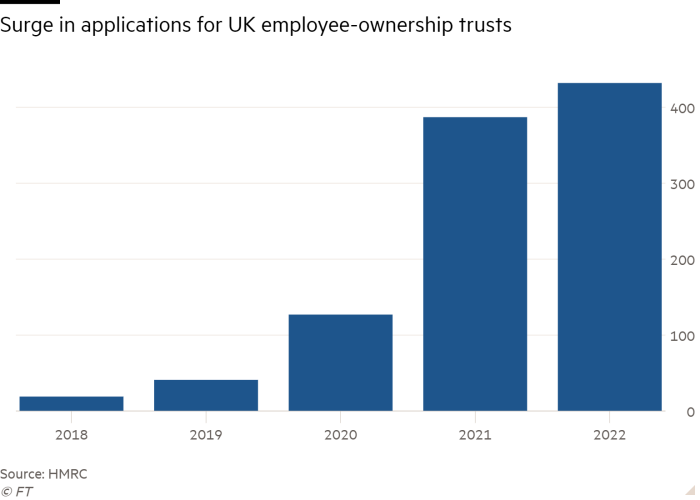

CleanTEC is not alone. The number of businesses selling a majority stake to an employee-ownership trust, known as EOT, has mushroomed in recent years, which experts say is down to growing awareness, and the increasing value of key tax incentives. FT Money takes a look at the rising popularity of EOTs.

A tax-friendly exit

EOTs were introduced in 2014 by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat government, to encourage corporate structures similar to the John Lewis model, where staff are partners in the company.

Business owners can avoid all capital gains tax if they sell a stake of at least 50 per cent into an EOT which has the company’s employees as its beneficiaries. The founders are paid gradually from company profits via the trust. Sometimes a bank loan is used to fund an initial upfront payment.

HM Revenue & Customs received more than 430 applications for EOTs in 2022, up from just 19 five years previously. The capital gains tax relief of 100 per cent has become more valuable since 2020 when the amount of CGT relief that entrepreneurs could claim on selling a business outright was slashed from £10mn to £1mn.

Meanwhile, research suggests employee ownership can make businesses more productive, empower staff, and protect jobs. RM2, a specialist employee share scheme and employee ownership trust adviser, estimated in 2022 that the median productivity increase across the 50 largest employee-owned businesses was 5.2 per cent year on year according to the company’s most recently published accounts — double that of the national average.

Carole Leslie, director of Ownership Associates, which helps companies transition to employee ownership, says EOTs have become the “go to model”, because they represent a “safe, secure structure” that is less expensive to run than direct employee ownership.

But lawyers say the route to success is not always straightforward.

What’s in it for business sellers?

While capital gains tax relief is a “major factor” in capturing the attention of business sellers, the purpose usually goes well beyond the tax relief. Garry Karch, head of EOT Services at law firm Doyle Clayton, has worked on setting up 60 or 70 EOTs over the past seven years and says: “I’ve only had one or two where it’s been really apparent that the only reason they are doing it is for the CGT relief.”

The biggest driver for many sellers, like Rochford, is legacy. FT Money spoke to seven entrepreneurs which have sold their holdings to EOTs in recent years, and the key motives were to protect the company’s culture, reward employees and be able to step back slowly from the day-to-day running of the business.

“It’s about sellers not wanting too much change, wanting to protect their employees and wanting to manage their exit,” says Leslie, who has worked on around 100 of these deals. But she adds that it requires “a lot of confidence from the sellers that the company will generate sufficient profits to pay them back”.

The risk for the sellers is that there is no guarantee they will receive the full sale price — with repayments from the trust contingent on future profits. Sometimes the trust can take out a bank loan (with a company guarantee) to speed up the payment, but this adds to cost and banks have historically been reluctant to lend for EOT financing.

Advisers also warn that business owners selling to an EOT may not get a valuation as high as could be possible with a trade sale, when, for example, a buyer can slash costs by shedding overlapping functions.

But Karch’s view is that sellers should still get a fair value for the sale. “You’re not going to get synergistic trade sale value, but you should get full value,” he says.

A 2020 study by professors Andrew Pendleton of The University of New South Wales and Andrew Robinson of the University of Leeds, found that some 60 per cent of business sales to EOTs had been at market value over the previous six years, around a third at a discount to market value, with a small minority gifted.

Sales to EOTs tend to be made at a valuation multiple of about four to six or seven times earnings, experts say, depending on the type of business. EOTs have become particularly popular among professional services firms, because their real assets are their people, according to the Employee Ownership Association, which represents employee-owned businesses.

Stuart Bell, 45, sold his recruitment company Robertson Bell, which employs around 50 people across Northamptonshire, London and Cape Town, to an EOT last March. He does not have plans to leave the company any time soon, but wanted to diversify his assets, and set the firm up so that it can later run without him.

Bell’s view is that the EOT structure does not work without the tax incentive. “I think you need it because there’s quite a significant risk for the sellers. Otherwise, why not go down the trade sale route?” he says.

Karch provides a hypothetical example. If you sold your business in a trade sale for a profit of £10mn, and the sale qualified for business asset disposal relief, the overall CGT would be 10 per cent on £1mn plus 20 per cent on £9mn. Sell to an EOT and you save that £1.9mn.

Say the valuation is based on five times £2mn of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation, then the CGT relief is “basically worth almost another one times Ebitda”, says Karch.

What’s in it for the employees?

If an EOT company is later sold, for example to a trade buyer, then employees, as the trust’s beneficiaries, share in the proceeds, after debts and taxes are paid.

But, before such a sale, employees in an EOT do not directly own the company, so they are limited in the rewards they receive.

David Pett, a barrister at Temple Tax Chambers, London, says that while the legislation affords “generous tax relief to individual company proprietors, it does not enable individual employees to benefit financially from the growth in capital value of the company to which they contribute by their labour”.

Under EOT rules, all staff can be paid an annual bonus up to £3,600 per year free of income tax (but not national insurance) — a threshold which has not increased since 2014, despite inflation.

A controversial feature is that the bonus cannot be paid according to an individual’s performance but is based on length of service, salary or hours worked, or a combination of these factors.

EOT-run businesses say the key benefits come from greater staff engagement and enhanced job security for staff. Mike Watret, operations director of Carlton Bingo, which became the first gambling company to transition to an EOT in March last year, says that when presented to staff, the greatest attraction for them was reassurance that the business would not be sold to a third party.

“A lot of staff didn’t understand the model at first,” says Watret, whose company runs 10 bingo sites in Scotland. “There was a lot of concern about job security, which is typically lost under a trade sale.”

If an EOT-owned business is sold, then, like the bonuses, the after-tax proceeds are distributed on “same terms” meaning based on length of service, salary, hours worked or some combination of the three.

Employees, who leave a firm before an EOT sale, may still benefit from the proceeds if they left on good terms and if the sale happened within two years of their departure.

Share option schemes

While the tax-free annual bonus is capped at £3,600, many companies transitioning to an EOT will also set up a share option scheme for key staff — perhaps through an enterprise management incentive (EMI) scheme, which lets small companies offer staff share options free of income tax.

Karch says that about 90 per cent of EOTs he sets up also have share option schemes, normally EMI schemes, for key staff who can usually buy shares at a “pretty significant discount” to the pre-completion value of the company.

When Rochford sold CleanTEC, which employs 2,100 people from Glasgow to the Isle of Wight, he and his co-founder kept a small holding, but transferred 72 per cent to an EOT and 12 per cent to an employee benefit trust. The EBT incentivises key staff with share options if performance targets are met.

What could go wrong?

The EOT is a relatively new structure, with the surge in popularity only coming in the past couple of years. As with any structure with tax advantages, HM Revenue & Customs worries that it could be exploited.

“HMRC always works a few years in arrears so we are yet to see to where it doesn’t like the ways businesses are using EOTs,” says Simon Blake, partner at accountancy firm Price Bailey.

The current legislation for EOTs does not require business sellers to get independent valuations, although it is a requirement for many professionals working on the deals. This leaves the scheme open to the possibility of abuse — where sellers ascribe a higher price to the business than the market value, even if trustees — who are appointed by the sellers — are not supposed buy the company for more than market value.

Pett says he has seen a situation where business owners want to sell to a trade buyer, but planned to sell 51 per cent to an EOT, free of CGT, and 49 per to a trade buyer. The deal, he says, was on the tacit understanding the trade buyer would later buy the remaining 51 per cent, with the EOT bearing the capital gains tax burden, rather than the seller. This, he says, is “basically a tax avoidance scheme”. As far as he is aware, the proposed sale is still “on the table”.

As a vehicle for business owners wanting to realise value from a business without selling to an external party, the EOT has so far proven successful. But the structure is new: as it becomes more popular, scrutiny will tighten.

Companies that took the plunge

Riverford: ‘a philosophical thing’

“For me [selling to an EOT] was a philosophical thing, I wanted what was best for the company,” says Guy Singh-Watson, founder of organic vegetables farm Riverford, who sold 74 per cent of the business to an EOT in 2018 for a fraction of the market rate. He says he had venture capital investors calling him up daily with proposals about how they could “maximise value” and “lubricate a sale”, with no mention of implications for employees, suppliers or customers.

“Speaking to them I felt like letting them buy the company would have been like selling one of my children,” he says. He looked at different ownership models, including direct share ownership, which he thought might better foster an entrepreneurial culture, but decided the EOT model left staff on a more equal footing as it does not leave richer employees able to buy more shares than the less well off.

“I worried we’d be a bit boring under the EOT consultative model [because staff are not directly incentivised], but in the end I went with it because I thought it was fairer, and I think we made the right decision.”

Kidzcare: tax-free employee bonuses

Anne-Marie Dunn, founder of Kidzcare, which runs four nurseries and six after-school clubs, had been looking for an exit for the company she founded 22 years previously. But she was reluctant to sell to a larger nursery, because she wanted to pass the business to employees.

However, she could not see how to sell to the staff without saddling them with debt — until she heard about EOTs. “I didn’t know about EOTs, I found out about them through a friend, and once I learned about the mechanism I moved it to an EOT within six months,” she says, speaking the week after she stepped back as managing director.

Dunn, who sold a 100 per cent stake to the EOT in January 2022, hopes that the structure will become a selling point as the childcare industry struggles with staff retention. The company’s 150 employees were all paid a tax-free bonus out of the trust last year, the first staff bonus at Kidzcare.

Union Industries: ‘we are accountable to shareholders’

Union Industries, Leeds-based maker of high-speed roller doors for the likes of Tesco and Aldi, was an early EOT adopter in a deal done by founders who retired.

Andrew Lane, the group’s managing director, says the group’s profitability and sales have “grown dramatically” since it transitioned to an EOT in 2014, with the group’s employee council ensuring employees have a say.

Two out of five members of the EOT trustee board are elected employees, who sit on the board for two to three years. Each year, one of the company’s three directors also resigns and stands for re-election, to ensure they remain accountable to the staff, who own the business. “It’s not communism, the directors and management make decisions and we are very fast on our feet, but we are accountable to shareholders,” Lane says.

.

[ad_2]

Source link