[ad_1]

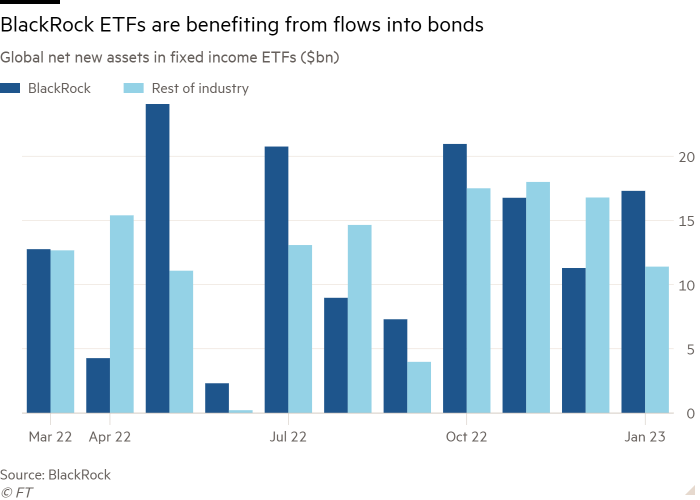

Enthusiasm for bonds is proving to be a bonanza for BlackRock’s fixed-income exchange traded funds, which have attracted more investor cash since US interest rates started rising than all their competitors combined.

BlackRock, the world’s largest money manager, is capitalising on growing interest among wealth managers and other asset managers in using ETFs instead of or in addition to buying bonds directly. From March last year to the end of January, there were $146bn net flows into BlackRock’s fixed-income ETFs, while competitors took in $134bn.

Bond ETFs have been a bright spot for BlackRock after a year when its overall assets under management shrank by nearly 15 per cent to $8.6tn. Chief executive Larry Fink considers them a main driver of revenue growth. BlackRock predicts that bond ETF assets industry-wide will more than double from $1.8tn now to $5tn in 2030.

The increases are being driven by regulatory changes, investors’ growing comfort with the way they perform in volatile markets and creative uses of them by wealth managers and even other bond funds.

“There have been significant changes about the way people think about fixed-income ETFs in the past year,” said Deborah Fuhr, founder of the ETFGI consultancy. “We have seen large funds and asset managers put their portfolios in ETFs . . . rather than buying bonds and trying to manage them themselves.”

“It’s a continuing trend. Once [people] have used an ETF, then they use them more and in different ways.”

BlackRock got into fixed-income ETFs early and has long been the largest player: it has more than 40 per cent of global assets under management for the category. But as competition for broad-based and retail-focused ETFs grew, it expanded into new areas. The number of fixed-income ETFs it offers nearly doubled from 243 to 462 in the past five years.

“We’re finding and expanding into all parts of the bond market in multiple different slices . . . Any part of the bond market that can be accessed through an ETF, we’re capturing that,” said Salim Ramji, BlackRock’s global head of ETF and index investments.

The narrow slices include ETFs such as IBTG, which only holds US Treasury bonds maturing in 2026, or LQDB, which purely contains BBB-rated corporate bonds.

That allows active fund managers to use them in a variety of ways. Some use a specific slice to tilt their portfolio either to longer or shorter duration bonds, depending on their view of the economy. Others use BlackRock’s AGG broad index fund as a holding tank when they receive large inflows so they can put money to work immediately, while also giving their active managers time to pick up the right bonds.

“We use ETFs because it is operationally quick and easy to do. It’s a quick way to gain exposure to a whole series of bonds,” said Wylie Tollette, chief investment officer of Franklin Templeton Solutions. If “you are out buying and selling the bonds directly, you are paying an embedded commission. If you added up the round-trip commission on the bonds, the ETF fee is very reasonable.”

Professional investor interest in bond ETFs really started to rise after many oil and gas companies failed in 2015. At that time, short selling BlackRock’s high-yield bond ETF turned out to be a better hedge against junk bond defaults than buying an index of credit default swaps because the ETF tracked the high-yield bond market more closely.

“We started to get a lot of inquiries from actual bond traders . . . until that point ETFs were probably more utilised by bond market tourists,” said Samara Cohen, chief investment officer for BlackRock’s ETFs.

Regulatory change has also driven take-up: in December 2021, New York state regulators started letting insurers treat passive fixed-income ETFs just like bonds for the purpose of calculating capital requirements. That made the products more attractive to a swath of the industry, and other states have been following suit.

Ramji said that BlackRock ETF users include nine of the 10 biggest active managers and eight of the 10 biggest US insurance companies.

Some money managers are sceptical of the trend, arguing that as active investors they find it difficult to justify putting money in another company’s passive funds.

“The layering of fees on fees is a real concern internally,” said one portfolio manager at a large fund house who did not want to criticise peers publicly. “At this point we’ve decided the ‘costs’ don’t outweigh the benefits.”

BlackRock’s nearest competitor, Vanguard, has opted for an entirely different strategy. It has 48 fixed-income ETFs with $389bn in assets, up from 38 with $150bn in 2017. The Pennsylvania-based group, which caters mostly to retail clients, said it has opted to tailor its selection to reflect “investor preference for low-cost, broadly diversified fixed income ETFs”.

But many fixed-income investors say the growth of bond ETFs has fundamentally changed the market for the better because of their structure. ETF shares trade throughout the day on exchanges, and more than 80 per cent of bond ETF trades take place without requiring the purchase or sale of the underlying securities, which adds liquidity.

In addition, the market makers who buy and sell the actual bonds that back ETFs have grown more comfortable with pricing large chunks of securities.

“Five years ago, when we would want to sell $20mn, $25mn of corporate exposure, we would have to do it line by line. Now dealers are able to price it as a block,” said John Gentry, head of the corporate fixed-income group at Federated Hermes. “This has helped us find bonds that we could not find before.”

Manuel Hayes, senior credit portfolio manager at Insight Investment, said using ETFs can help shrink the cost of buying high-yield corporate bonds from roughly 60-80 basis points to 15bp or 20bp. “ETFs are here to stay and they are evolving. If you overlook it you are missing half the market,” he said.

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

[ad_2]

Source link