[ad_1]

Richard Klin is fed up with the buy-to-let business. The 43-year-old entrepreneur and investor is no accidental landlord: he began buying homes for rent over two decades ago as a student and amassed a portfolio of 200 properties across London, Liverpool and Devon.

Based in London, he owns most of these homes through a limited company, but a significant number are held in his own name. And it is the growing burden of tax and regulatory compliance on these individually-owned properties that has made him determined to start putting up the For Sale signs.

“Over the coming years I intend to sell all the properties I own in my own name,” he says. “I’ll gradually move my capital to other sectors, in my case a chain of coffee shops and technology investments . . . Regulation and tax changes have fundamentally changed the economics of investing in the sector. I know many other landlords doing the same.”

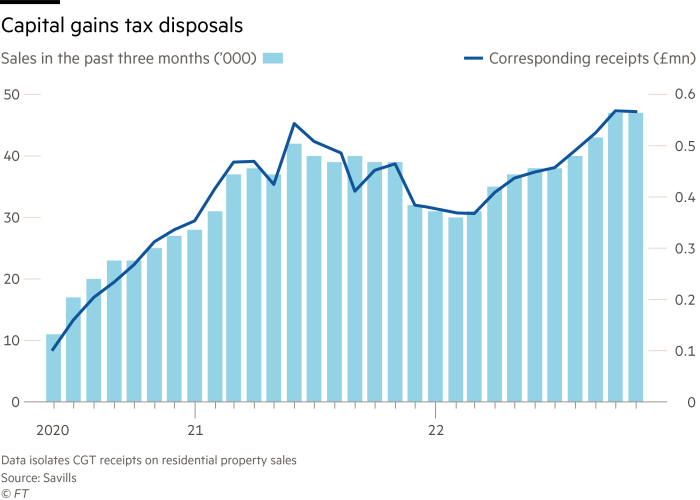

There is no shortage of reasons why landlords are choosing to scale down their activities in the private rented sector, ranging from higher taxes and red tape to costlier mortgages and a house price slowdown. As more legislation looms, a further toughening of the rules and higher implied costs appear inevitable. New analysis of HM Revenue & Customs data for FT Money clearly suggests the pace of buy-to-let sales has picked up over the past year.

But there are others who believe the current phase of adversity will create opportunities. They contend the nimble investor will be able to pick up bargains from overstretched or frustrated landlords; that the careful selection of location and properties will bring sustainable profits; that rental demand and rent levels look strong; and that stability will return to interest rates and house prices over the next two to three years.

“The reality is there’s only a certain number of property investors who have the funds available and are willing to invest at this point. That makes my life easier,” says one London-based landlord looking to expand in the north of England. “You know there’s going to be more deals out there.”

As the cost of living crisis continues to bite and workforces look increasingly vulnerable to cuts, however, the sustainability of higher rents has come into question — as well as the willingness of landlords to take on the risks and administrative burdens of the business. Speaking to investors, lenders and housing experts, FT Money explores the uncertain outlook for Britain’s buy-to-let sector.

The case against

In the three months to the end of November 2022, the estimated number of buy-to-let or second homes sold hit a record 47,000, an increase of 21 per cent on the same period in 2021, according to estate agent Savills, which analysed capital gains tax (CGT) receipts from HMRC.

In the five years to 2013-14, there were an average 61,100 property sales a year incurring CGT. That doubled to 123,600 a year in the five years to 2021-22 — and peaked at 141,000 in 2021-22, the data show.

Lucian Cook, residential research director at Savills, points to the “double whammy” of higher mortgage interest rates and the end of mortgage interest relief in 2020, as well as expected government rule changes on energy efficiency and rental rules. In addition, many landlords who have been active since buy-to-let took off in the early 2000s are now nearing or in retirement and looking to liquidate assets.

“It’s a reflection of the increased financial pressures on landlords,” Cook says. “You’ll be left with a core of committed landlords who run it as a professional business. But a lot of people for whom the investment has become more marginal will be taking a second look at it.”

Howard Davis, founder of the Bristol-based agency Howard Independent Estate Agents, says many long-term landlords in the city are now looking to sell — as he speaks to the FT, he has on his desk three valuation requests from landlords. They are “squeezed from all sides,” he says. “It’s almost an everyday conversation for me at the moment.”

Those who have increased mortgage debt face higher interest rates on fixed rate home loans, despite them easing back in recent weeks. The average rate on a five-year buy-to-let fix across all loan-to-value ratios was 3.16 per cent at the beginning of February 2022, according to finance site Moneyfacts. Today it stands at 6.12 per cent, down slightly from 6.72 per cent in November.

Rachel Springall, a financial expert at Moneyfacts, says there are signs of a recovery in the number of deals available to landlords. However, she adds: “Both the average two- and five-year fixed buy-to-let rates have come down in recent months, but both stand above 6 per cent.”

Lenders restrict the amount of debt buy-to-let borrowers can take out as a proportion of the home’s value, typically to 75 per cent, and insist on a minimum headroom in the relationship between expected rents and interest payments of 145 per cent. Most landlords take out interest-only loans, which amplify the effect of mortgage rate changes on their monthly payments.

Simon Gammon, managing partner of mortgage broker Knight Frank Finance, says the “full shock” of the mortgage rate rise has yet to hit landlords, but will intensify later this year as more fixed rate terms come to an end. He says he is already seeing more landlords facing a restricted choice when refinancing, because rental income — even with rent rises — no longer meets the lender’s required interest coverage.

“The only way they could make it work would be to significantly reduce the loan or put the rent up. People are increasing rent, but not enough to cover the mortgage as it is. So they’re stuck with their existing lender.”

Calculations by Aneisha Beveridge, research director at estate agent Hamptons International, show how an average landlord’s profit dwindles when they remortgage under higher interest rates.

The research takes the example of a landlord who bought a £200,000 buy-to-let in January 2021, with a 75 per cent loan-to-value mortgage fixed for two years and running costs (excluding mortgage payments) amounting to 31 per cent of their rental income.

At an average yield in England and Wales of 6 per cent, the average landlord — owning in their own name and paying the higher rate of income tax — would be likely to see their mortgage payments rise by 117 per cent when they refinance — turning a £2,500 annual profit into a £365 loss.

“Essentially, the average higher-rate taxpaying landlord will now need to be yielding 7 per cent or more in order to turn a profit at today’s rates, compared with a gross yield of 3 per cent in 2021 when interest rates were lower,” says Beveridge. “So it’s likely they will either be forced to sell or inject additional equity, either from savings or the sale of another property.”

Opportunity knocks

Plenty of property investors believe such prognostications are unnecessarily doom-laden, pointing to fierce demand for rental housing. November figures from property website Zoopla found rental inquiry levels at lettings agencies running at 46 per cent above the five-year average.

Houses in multiple occupation

Houses in multiple occupation (HMOs) — an official definition given to properties shared between households with common areas such as a kitchen — is one option for landlords looking to increase their rental yields.

One landlord-investor, who asked not to be named, is looking to add a student HMO in the north-west to his portfolio over the next 12 months. “I could go out and buy four or five single homes. But for the money, the cash flow would be nowhere near as healthy as with an HMO.”

It is fair to say HMOs typically generate higher yields, particularly on a gross basis, says Aneisha Beveridge, research director at agent Hamptons International. But they also come with expectations that landlords will foot the bill for lots of running costs. “Given most of these landlords will pay for bills such as heating, electricity and council tax, I suspect their net yield is being squeezed quite tight,” she says.

Landlord Richard Klin has invested in HMOs for 20 years and says there is a clear yield benefit. “But there are increased costs of compliance, maintenance and wear and tear, and some councils are restricting the number of new HMOs allowed, for example in student areas . . . A lot of passive landlords will probably continue to prefer more standard rental stock, while the more ambitious and active will be driven to HMOs.”

Davis, the Bristol estate agent, says a two bedroom flat in the city’s Clifton area now rents for £1,200 a month, when three years ago it would have fetched £950. Yet a shortage of stock means demand remains intense. “We have to have staff here when it goes on to Rightmove because the phones go nuts when tenants receive their alerts. We could rent it 100 times over.”

According to property site Zoopla, UK rents rose 12 per cent in the year to October. Klin said rents had held up well in his Liverpool and Devon properties, and had come roaring back in central London after imploding during the pandemic. “Liverpool and Devon rents continue to increase roughly in line with inflation. London rents are outperforming inflation by some margin, often in excess of 20 per cent as competing landlords have sold up or at the very least not invested in new supply.”

Some question the extent to which landlords will face widespread refinancing problems. Richard Rowntree, managing director of mortgages at buy-to-let lender Paragon, says: “We have seen scaremongering with regards to payment shock, but the reality is different . . . The underlying fundamentals in terms of supply and demand are still very strong.”

He disputes warnings that landlords will face a tripling of their interest burden when they refinance. “We’re seeing landlords coming off five-year deals that were around 3.5 per cent, and they can secure rates at close to, or even below, 5 per cent.”

‘Buy the dip’

One landlord looking at the positive signs is Ollie Vellam, a London financial services professional, who owns two buy-to-lets in Abbey Wood, south-east London, and in Liverpool.

The 33-year-old says he expects landlords to sell up in earnest after the government brings in new energy performance rules. Originally scheduled for 2025 for new tenancies, but still to be confirmed, these could cost landlords up to £10,000 to rectify less efficient homes. That’s where Vellam sees his chance: “I’ll then buy the dip when there is more supply.”

As a long-term investor, he sees himself holding his Liverpool home — and more to come — for perhaps 30 years, to build what he describes as “a decent additional pension on top of what I’ll get from my regular employment”. But he won’t be looking for more homes in London, where high prices mean lower yields. “My target areas are going to be Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield. You just get so much more for your money.”

Zoopla’s data underlining rental demand also contain less welcome news for those landlords hoping to offset their higher mortgage costs with steeper rents. Rents are less affordable for single tenants than at any time in the past ten years, now accounting for 35 per cent of the average income of a single earner.

The London-based landlord looking to buy in the north of England, who asked not to be named, acknowledges the dangers of taking on mortgage risk at a time of high uncertainty. But he adds: “You wouldn’t be in this property investment game if you weren’t open to at least some risk, would you?”

Company vs individual ownership

Ollie Vellam, who works in the City of London, is well placed to judge the merits of corporate versus individual ownership. He owns an Abbey Wood buy-to-let property with a relative — both as individual owners — and a Liverpool one through a limited company. And he believes only corporate ownership — at least for mortgaged owners — has a bright future.

Until 2017, landlords were able to offset the costs of mortgage borrowing against their rental income when calculating their taxable profit, if they held a property in their own name. But the relief was withdrawn over the four years to 2020.

This has scythed into returns for many, particularly higher-rate taxpayers. Those owning in a limited company can still gain relief on interest payments, which explains the structure’s growing popularity for landlords. But switching ownership of an existing home into a limited company will usually incur a tax charge, including capital gains on the transfer.

“I don’t think there’s much scope to invest on an individual basis,” he says. “There’s only going to be profits to be made through a limited company.”

Buy-to-let experts believe the loss of the relief is leading to more professional landlords running portfolios as their main source of income. Richard Rowntree, managing director of mortgage at lender Paragon, says the few examples of selling seen recently have been by “amateur landlords”, who typically own in their own name.

“Smaller-scale landlords often get into buy-to-let accidentally and, in any event, they have been gradually exiting the market in recent years — a trend that may well continue.”

[ad_2]

Source link