[ad_1]

Everything tells you the time nowadays. The hours and minutes blink on the bottom right-hand corner of office computers and are displayed on the smartphones we check countless times throughout the day.

Despite this, there is a growing queue of people waiting to spend $15,000 on a Rolex Daytona. The premium timepiece has a wait list of over five years, according to Bernstein research. The fashion for horological wrist jewellery has driven strong sales at UK-listed retailer Watches of Switzerland (WOSG).

Lex Populi is a new FT Money column from Lex, the FT’s daily commentary service on global capital. Lex Populi aims to offer fresh insights to seasoned private investors while demystifying financial analysis for newcomers. Lexfeedback@ft.com

The desire for a Daytona points to key peculiarities of the luxury goods industry and explains why the sector is so attractive for investors.

Luxury products are “positional goods” in economic parlance — and status symbols in common usage. Demand waxes with the wealth of nations and the fortunes of elites. China has provided a secular impetus for decades.

The luxury sector is only modestly cyclical because well-off people are insulated from the worst impacts of downturns. Price points do not reflect the manufacturing cost of an item with a small margin on top. Important expenses also include posh shops with prestige addresses, celebrity-laden launches and glossy advertising.

But ultimately, luxury goods groups set prices to exclude middle to lower income shoppers. Witness the fury of Patrizia Gucci on finding street vendors selling licensed knock-offs in the movie House of Gucci.

Many companies have delivered strong revenue growth even as recession starts to bite. Third quarter sales were up by around a quarter at leather-goods maker Hermes and Cartier-owner Richemont.

LVMH, the biggest luxury group in the world with a market value of €365bn (£315bn), increased sales by almost a fifth. No wonder owner Bernard Arnault has knocked Elon Musk off the podium as the world’s richest man.

Healthy sales sit atop rich operating margins. At 42 per cent, Hermes profitability is more than three times that of popular consumer brand Nike. No wonder the sector has traditionally commanded premium valuations. Hermes trades on a staggering 50 times 2022 earnings.

WOSG is smaller and less prestigious. Its first-half revenues rose 31 per cent as the average price of watches increased and customers opted for more expensive models. The retailer, which has only a fraction of the margin of big brand owners, trades on 18 times forecast earnings after a share price fall this year. The former mid-cap darling has underperformed larger peers after a strong run in 2021.

Lex has favoured brand holders, notably LVMH, over pure retailers.

The perennial question is whether demand for luxury goods can last. We believe it will. The luxury sector benefits from the megatrend that is rising inequality. Automation rewards technocrats while hollowing out lower income professions, where earnings are treading water or falling. Political pushback is too muted to reverse the flow.

That is uncomfortable if you believe in redistribution. But the coldly rational investor should invest in luxury goods companies — and dollar stores.

Tui much information

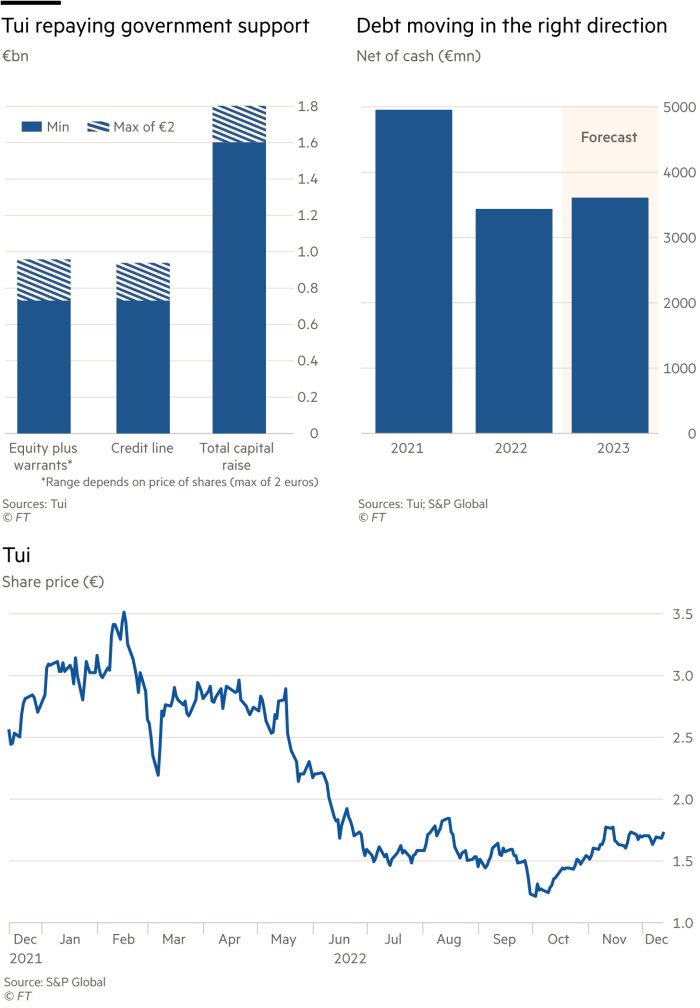

Like its clients, Tui just wants to get away. The big European travel company, listed in both Germany and the UK, aims to shift from being a state-supported group to fully independent. It plans to raise €1.6bn to €1.8bn of capital for this purpose. Good thing too.

The deal would represent a milestone in the recovery of the European holiday industry. Tui was an early indicator of trouble ahead as coronavirus spread. Back then, Lex cited the soaring cost of insuring against defaults on Tui bonds as a danger signal.

Tui would have gone bust without bailouts from the likes of the Berlin economic stabilisation fund (the WSF) and the German state investment bank (KfW). Shareholders will now have to stump up, creating an overhang on the stock next year.

During the pandemic both the WSF and the KfW helped rescue Tui with equity capital and the offer of loans. The company paid back some of the government equity funds this year. But shareholders disliked the state retaining a stake.

Lex dislikes this too. Political control — except of an indirect kind, via markets regulation — makes stocks tough to analyse and uninvestable as a result.

The WSF originally put in €479mn, including some equity warrants at a strike price of €1. Tui’s stock price closed on Monday, when the repayment announcement was made, at €1.48.

Taxpayers should profit. Using a set formula, both sides agreed to a repayment of no less than €730mn (at €1.68 per share) and no more than €957mn (€2 per share).

Expect a bumper capital raising, assuming shareholder approval, of no less than €1.6bn early next year, which will also reduce any perceived need for government credit lines. That is equivalent to well over half today’s market capitalisation and should restore Tui to independence.

The company is detaching itself from the apron strings of the state because its business has taken off again. Customer bookings in the fourth quarter to September were at 93 per cent of the same period of 2019. Even better, net debt fell by 30 per cent to €3.4bn, an indication of Tui’s positive free cash flow. Net debt to ebitda remains a hefty 3.2 times.

Analyst forecasts for debt show they do not expect immediate improvement. Nor does the market. The shares fell 8 per cent on Tuesday to only a quarter above the pandemic trough. Shareholders will need to see a steeper trajectory on bookings before they agree to commit more capital.

Lex liked Tui’s proposition before the pandemic set in. It has plenty of scale, took the battle to its online-only competitors on the web and has created differentiated offers for holidaymakers. As state control rolls off, keep an eye open for buying opportunities.

[ad_2]

Source link