Is our world getting better and likely to continue to do so or is it sitting on the edge of catastrophe? People who think about these questions tend to divide sharply into the cheerful optimists, who believe the former, and the gloomy pessimists, who insist on the latter. I am in the former camp. But I would also make an important caveat. Continuing progress depends on managing the dangers we ourselves have created. Among these are destruction of the planetary environment and thermonuclear war. To succeed we must overcome forces of division, within and among countries, that threaten social stability, global co-operation and peace. In sum, the world can be a better place. But we cannot take for granted that it will be.

An optimistic view of the past is contained in the Human Development Report 2021/2002 from the UN Development Programme and Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2022 from the World Bank. The latter shows, for example, that the proportion of the world’s population living in extreme poverty (now measured at an income of less than $2.15 a day) fell from close to 60 per cent in 1950 to 8.4 per cent in 2019. That is staggering. Similarly, the UN’s human development index — an amalgamation of national income per head, years of schooling and life expectancy at birth — also shows a substantial and steady rise from 1990 to 2019. Again, the World Happiness Report 2022 shows that the happiest countries are prosperous — and, interestingly, small — ones, with Finland and Denmark at the head of its list. Average prosperity may not be a sufficient condition for greater happiness. But prosperity helps.

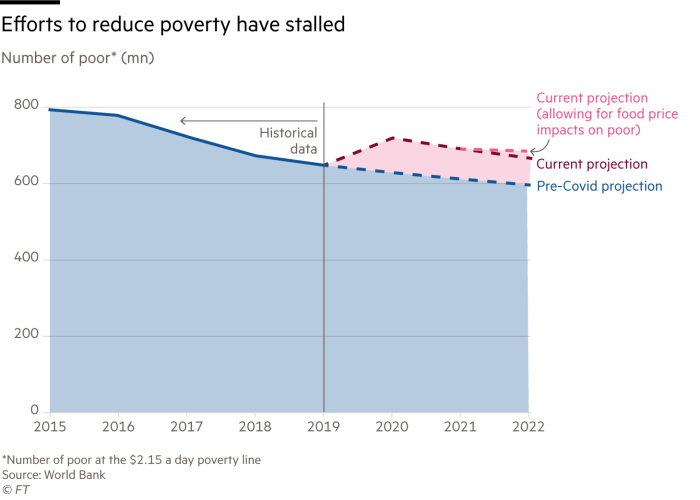

Not surprisingly, the pandemic reversed progress. The number of people in extreme poverty jumped from 648mn in 2019 to 719mn in 2020. Worse, it may mean that the numbers in extreme poverty will be permanently higher than they would otherwise have been. Again, the human development index is estimated to have declined in both 2020 and 2021, erasing gains of the previous five years. The energy and food crises brought about by Russia’s war in Ukraine will surely prolong the losses. The human consequences of these twin shocks then are unquestionably huge.

One might assume that normal economic service will ultimately be resumed. Yet the Human Development Report suggests that this hope might not materialise. It points to today’s “uncertainty complex”, as crises pile up one upon the other. Covid-19 is not, it suggests, a “long detour from normal; it is a window into a new reality”.

Yet it is also true, as the report shows, that the response to Covid included the speedy discovery and development of effective vaccines. Thus, “in 2021 alone Covid-19 vaccination programmes averted nearly 20mn deaths”. The distribution of these vaccines has been horribly unequal and the response has too often been one of ignorant hostility. But they worked. So, why be so pessimistic?

This “uncertainty complex” consists, suggests the report, of three elements: the planetary changes of the “Anthropocene” — the period of human-induced changes in the biosphere; profound social and technological changes; and political polarisation, within and between societies. The first is indeed novel. Both the second and third have been characteristic of our world since the 19th century. What is new today is how planetary forces interact with the domestic ones. We cannot now solve our domestic problems without solving our global ones. But we may also find it impossible to solve our global problems without first solving our domestic ones.

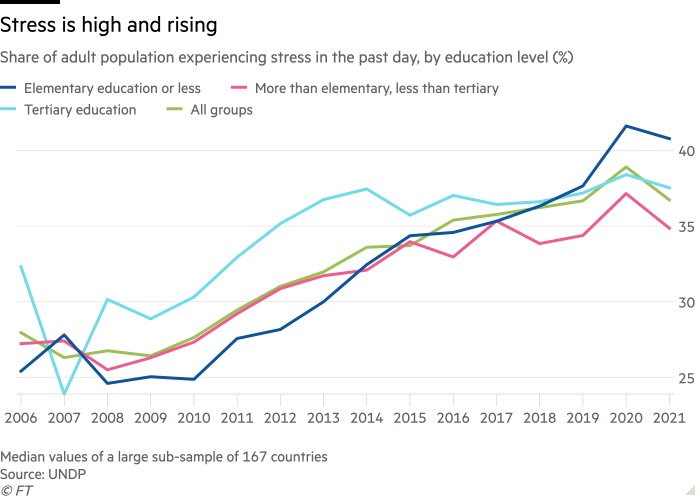

The report gives fascinating evidence on three aspects of those domestic difficulties, rooted, it asserts, in uncertainty. First, there are rising levels of mental distress. Strikingly, data “paint a puzzling picture in which people’s perceptions about their lives and their societies stand in stark contrast to historically high measures of aggregate wellbeing”. Second, insecure people can be attracted to “social identities that become an ‘antidote’ to uncertainty, social identities that are in part affirmed as being different — at the limit completely opposite — from others”. Finally, that process can lead to political polarisation and, to take a worrying example, rejection of democratic norms.

These domestic phenomena, worsened by inequality, interact with changes in global power and influence to destabilise international relations. Thus the interaction of domestic with global conflicts makes it even harder to sustain world peace and planetary stability.

This emphasis on the interaction between social, technological, economic and political developments may add a dimension to discussions of the “polycrisis”. But it does not make meeting the challenges themselves easier.

The report itself suggests “three I’s” — investment, insurance and innovation. All three make sense. If we are to improve the performance of our economies and meet the planetary challenges, we need to raise investment across the world, and not just in historically successful economies. Second, social insurance against uninsurable risks, such as the loss of a job, the decline in one’s industry or failing health, will help reduce insecurity. Third, we need innovation. But the most important ones may now be social and political. The last period of such renewal was in the middle of the 20th century. We cannot wait for a second period of catastrophe before we attempt renewal once again.

We have made real progress, though it has been unequally spread within and across countries. But, as has always been true, progress creates new problems. We have also stumbled, often badly, on our road to the answers. If the optimistic view I still hold is to prove true, we have to stumble faster.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.