[ad_1]

Lex Populi is a new FT Money column from Lex, the FT’s daily commentary service on global capital. Lex Populi aims to offer fresh insights to seasoned private investors while demystifying financial analysis for newcomers. Lexfeedback@ft.com

Short selling has natural appeal for the sceptical private investor. Belying their sunny PR messages, many companies are risky and badly run. Profiting from share price drops seems like a smart strategy thanks to The Big Short and Skandal!

The Big Short movie chronicled short selling directed against US mortgage-backed securities while the Netflix documentary Skandal! told the story of fraudulent payments group Wirecard (on which FT reporters got the scoop).

Viceroy, a US short seller, is more prosaically targeting small UK investment trust Home Reit. The tussle usefully illustrates some salient features of short selling.

This contest is a very public battle. Viceroy’s allegations include the claim that significant numbers of Home’s tenants are not paying their rent or will be unable to do so. Home riposted with a detailed denial on Wednesday.

The market was unconvinced. Shares slipped further, taking losses for shareholders and potential gains for Viceroy to two-fifths. This showed the extent to which the balance of advantage resides with a canny short seller. Ordinary investors are easily spooked.

Invariably shares of a target company will fall regardless of the substance of allegations. The extent of that is often a function of how successful the short seller has been in past incursions.

A raid by Viceroy on German property group Adler at the end of last year made similar allegations to those it has levied at Home Reit. German regulators have since uncovered accounting irregularities. Adler’s shares have dropped by 85 per cent.

Short selling is old stock exchange practice, sometimes achieved these days via derivatives and a breed of bankers called prime brokers.

Classically, the bear sells borrowed shares, buying them back at a later date. If the buyback price is lower, the trade will be profitable. The difference with a long position is that returns cannot exceed 100 per cent, crystallised when a shorted stock falls to zero.

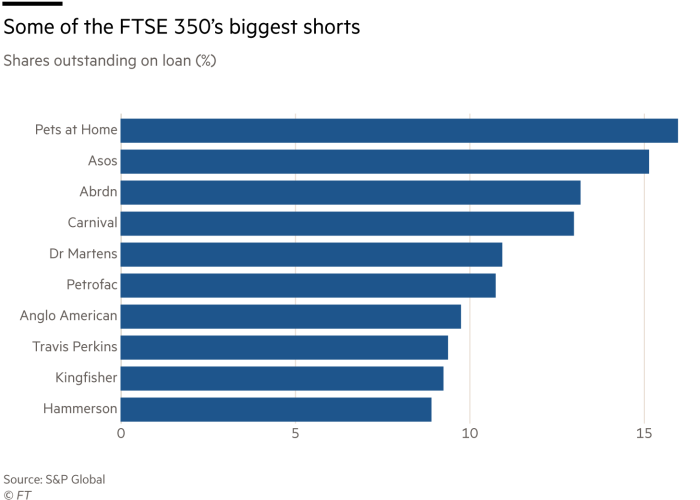

Professional investors often short shares without publishing a list of lurid allegations against the target. They simply doubt the optimism of bullish peers. Online groceries group Ocado was a top target for many years.

Short sellers can get their fingers burnt when shares rise sharply and then scramble to secure stock to cap their losses. This is known as a “short squeeze”.

This underlines the riskiness of short selling. The practice is also tricky for ordinary private investors to pursue. They can short stocks using contracts for difference from specialist retail brokers. These businesses may deal at terms highly disadvantageous to their customers. Extreme wariness is advisable.

Lex regards short selling as a legitimate market activity. It is foolish for regulators to ban shorting, as they sometimes do during bouts of markets volatility. They are only shooting the messenger. But we take a medium-term, long-only view of investment. We believe bad companies are for avoiding, not shorting.

Clever endeavour

Wise is a surprisingly straightforward proposition for a UK-listed fintech. It is not trying to be a bank. Nor is it offering a product no one knew they needed. Instead, the start-up specialises in digital international money transfers. Decent half-year results show there is enough demand for this service to justify the title “disrupter” for Wise.

Its costly shares reflect that. Valuing the stock using next year’s expected earnings per share make it look very expensive indeed. The ratio is over 60 times. Even as a multiple of sales, the stock is pricey at some 10 times.

The business looks a little cheaper when you consider that the eternal optimists of stock analysis forecast earnings growth of about 98 per cent annually for the next few years.

Correspondent banks charge an arm and a leg to move funds round the world. Wise and its peers undercut them. Developed economies are the target markets. Poor migrant workers transacting in cash in hot countries still rely heavily on unsatisfactory money agents.

Rich-world customers have delivered powerful growth. Three-quarters of revenues of £397mn in the six months to the end of September came from Europe, North America and the UK. Asia-Pacific provided £73mn and the rest of the world £29mn.

Add in interest revenue on customer balances of £19mn and total income was £416mn, a year-on-year increase of 63 per cent.

Wise expects total income growth for the full year of 55-60 per cent, with a compound annual growth rate of 20 per cent in the medium term. Higher-value services, such as a new debit card, will support revenue growth. The average transfer fee was 64 basis points of value, up from 62bp a year earlier.

Wise’s service compares well with high street banks charging 4 per cent or more. They still dominate the business, leaving room for growth.

Wise had 5.5mn customers in the second quarter, 40 per cent more than a year earlier. It will be harder to keep that pace of growth going amid downturns. More than two-thirds of Wise’s customers followed word-of-mouth recommendations. That will help. So will diversification.

Wise has a market capitalisation of just over £6bn, pegged as realistic by Lex when the company listed just over a year ago. This is hardly a value stock. But if you are seeking momentum, Wise has it.

[ad_2]

Source link