[ad_1]

Lex Populi is a new FT Money column from Lex, the FT’s daily commentary service on global capital. Lex Populi aims to offer fresh insights to seasoned private investors while demystifying financial analysis for newcomers. Lexfeedback@ft.com

Bosses love to expand the companies they run. The response of many investors is: “Stay focused: it’s my job to reduce risk by diversifying, not yours.” This could apply to Pets at Home, a UK-based retailer of food and accessories, keen to expand its market pawprint.

Ambitious chief executive Lyssa McGowan could point to half-year results this week in support of horizontal spread. Pets at Home has been expanding its veterinary business after a costly restructuring a few years ago. It is making a rising contribution to revenues and profits.

Economies of scale are often cited as a reason for companies to bulk up. Larger companies can buy supplies more cheaply and spread head office costs over a bigger revenue base.

Diversification can also create strains. For example, hotel operator Whitbread was under investor pressure for years concerning its fast-growing café chain. It finally sold the Costa Coffee brand to Coca-Cola for $5.1bn in 2019.

In a similar vein, Associated British Foods might as well be called Associated British Clothes, as one FT colleague quipped. The City cares most about its Primark clothing stores. Family control means no split is likely there.

Lex believes pragmatism applies to diversified businesses, which critics sometimes reflexively dismiss as “conglomerates”. Channelling cash flow from mature divisions into fast-growing ventures can make sense. Why not, so long as group performance is good?

Pets at Home also has the defence that it has diversified into activities that are adjacent rather than widely flung. Its three brands — Pets at Home, Vets4Pets and The Groom Room — share an online platform and, often, the same physical location.

The group plans further diversification. This week, McGowan noted the “huge space” between shipping a bag of dog food and doing surgery on a cat. She mentioned nutrition, wellbeing, preventive medicine, homewares, accessories, end of life care and training. Growth, she said, would both be organic and through “accretive M&A opportunities”.

McGowan joined six months ago from Sky, where she was chief consumer officer. Her digital marketing expertise should support the company’s strategy of building digital revenues, particularly through online subscriptions. The company’s Puppy and Kitten Club has 7.6mn active members.

Lex previously doubted whether the pandemic boost to pet spending in the UK would survive the end of lockdowns. Pets at Home has sustained sales momentum. Like-for-like revenues rose 6.4 per cent in the first half of the year from April, with most growth in the second quarter. Earnings before tax fell 9.3 per cent to £59.2mn — in line with projections and explained by an 11.3 per cent rise in underlying operating costs from energy, freight and digital investment.

At about 290p, shares are under their pre-pandemic peak and far below their high of almost 520p in September last year. The company is trading at around 14.5 times future earnings. For much of 2020, its valuation was double that or more. The shares are a decent medium-term investment. But McGowan should focus on building up the vet business before working through her lengthy shopping list of new ventures.

50 shades of green

Amundi, Europe’s largest fund manager, is causing ructions. It has declassified the majority of its $45bn of “really green” funds to “sort of green”. This highlights one of the problems with ESG investing: it is not yet clear what counts as a sustainable place to put one’s money. There are other — more fundamental — concerns, too.

Lex thinks the E, S and G of the ESG grouping is made up of categories that do not belong together. Environmental investment has scope to produce good returns because energy transition is necessary and inevitable. Social usefulness is a good deal more nebulous — note moves to reclassify defence shares as ESG shares. And governance is too often an exercise in box-ticking.

Within environmental investment, the question is what should qualify. Regulators do not want fund management groups labelling their funds as sustainable if they are not. Germany’s DWS faced accusations of such greenwashing this year.

Europe’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and taxonomy define what should count as green. It should force funds to label themselves according to their underlying investments. These policies should enable investors to put their money to good use in a measurable way.

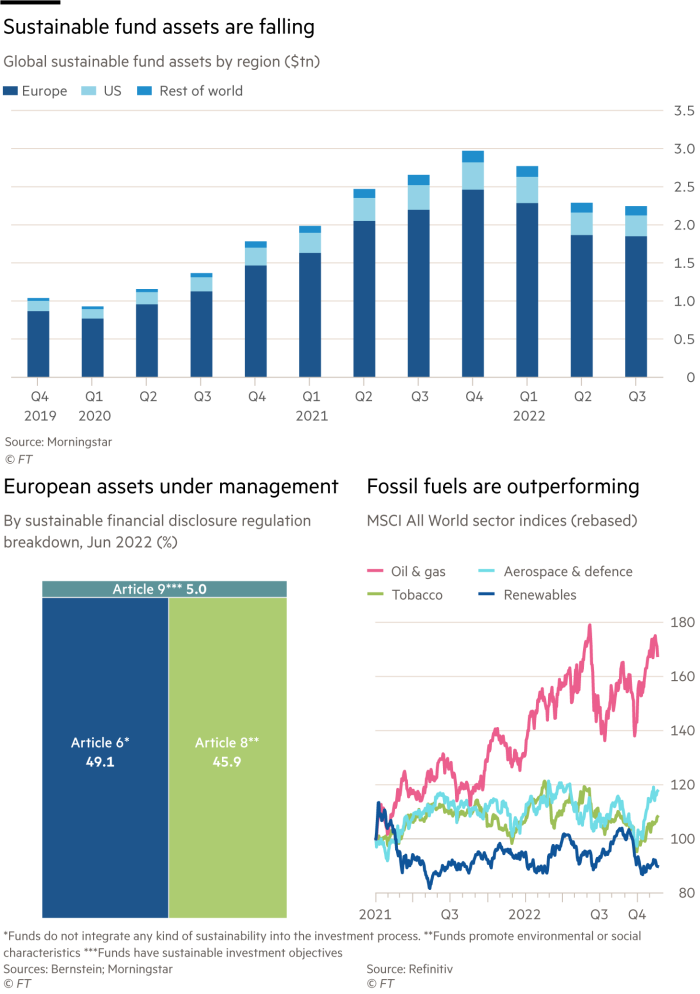

There is some evidence of success. More than 50 per cent of European funds are labelled as article 8 (light green) or 9 (dark green). Yet evolving guidance means 380 products changed designation in the third quarter, according to Morningstar research. This is what Amundi and some of its peers have done, partly to avoid legal challenges later.

The real question for investors is this: to what extent can green investments deliver higher risk-adjusted returns and help save the world in the process?

On the first point, environmental investments should have growth potential and lower risks. They will still suffer from economic cycles. Indeed, since the beginning of 2021, sectors frequently excluded from green funds — oil and gas, for example — have outperformed the wider market and renewable electricity.

As for saving the world, the danger facing any investor is that categories devised by bodies such as the EU may not chime with their own definitions. Use them as a guide rather than the gospel truth. Dirty companies that transform into clean ones may be worthier of investment than dud propositions laden with ESG awards.

City Bulletin is a daily City of London briefing delivered directly to your inbox as the market opens. Click here to receive it five days a week.

[ad_2]

Source link