[ad_1]

(Bloomberg Opinion) — The “unifying framework” that the US Bureau of Labor Statistics follows in designing the consumer price index, according to the agency’s handbook of methods, involves attempting to answer this question:

What is the cost, at this month’s market prices, of achieving the standard of living actually attained in the base period?

So, yes, it is a little weird that 24% of the latest CPI, the main US measure of inflation, consists not of market prices but of “the implicit rent that owner occupants would have to pay if they were renting their homes.”

This “owner’s equivalent rent” tends to make non-economists’ heads explode, generating frequent criticism from investors and others. But there’s no sign it’s going anywhere. From 1953 through 1982, the BLS used a different measure based mainly on the prices of new houses and monthly mortgage payments before abandoning it in the face of theory-based critiques from economists and practical concerns about how much volatility it added to the CPI. So, yes, owner’s equivalent rent is weird, but there doesn’t seem to be an obviously better alternative.

Some important questions are being raised at the moment, though, about how the BLS measures the rent from which owner’s equivalent rent is derived. Contrary to widely held belief, this is not done by asking homeowners how much they think their houses would rent for. That question is in fact asked but is used to determine the weighting that owner’s equivalent rent is given in CPI (the 24% mentioned above). The monthly changes that determine the inflation rate are estimated from changes in rents on similar dwellings, and those changes in rents are measured by asking thousands of American renters how much they’re paying. (The 7.4% of CPI that is actual rent is also measured by this survey.)

Does this truly represent market prices? That is, if you’re on a two-year lease, or you’re a long-term renter with a good relationship with your landlord, does the change (or lack of it) in your rent accurately reflect what’s going on with the cost of housing? Probably not, argued economists Brent W. Ambrose and Jiro Yoshida of Pennsylvania State University and N. Edward Coulson of the University of California at Irvine in a series of papers, the first of which appears to have begun circulating in 2012, and Adam Ozimek (now chief economist of the Economic Innovation Group, a Washington think tank) in a 2013 Temple University doctoral dissertation. Better to focus on new leases and thus measure what Ozimek called “marginal rents”:

Marginal rents reflect market turning points sooner, and show a larger post housing bubble decline in rents. In addition, marginal rents are shown to forecast overall inflation better than average rents.

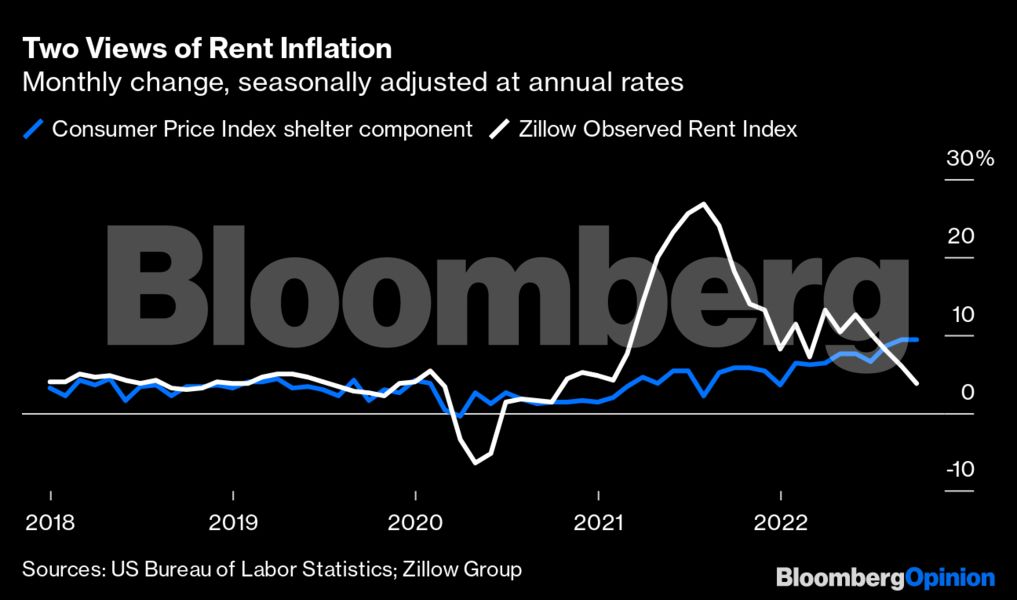

The experience of the past couple of years has done a lot to reinforce this view. Zillow publishes a monthly rent index that measures changes in asking rents for apartments and houses (so do Apartment List and CoreLogic, but I use Zillow’s here because it’s available in seasonally adjusted form), and it shows rent inflation accelerating rapidly during the first eight months of last year and decelerating since, while CPI shelter inflation increased only slowly last year and has kept rising this year.

Last month, the BLS released a working paper by two of its economists and two at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland that more or less endorsed this approach. The authors assembled their own rent indexes from BLS rent microdata and found that “rent inflation for new tenants leads the official BLS rent inflation by 4 quarters. As rent is the largest component of the consumer price index, this has implications for our understanding of aggregate inflation dynamics and guiding monetary policy.”

The most important of those implications would seem to be that the Federal Reserve’s policy-making committee was behind the curve when it started raising interest rates in March — a year after rents on new leases started exploding — and could end up late again in pivoting to easier monetary policy long after rents have started to fall.

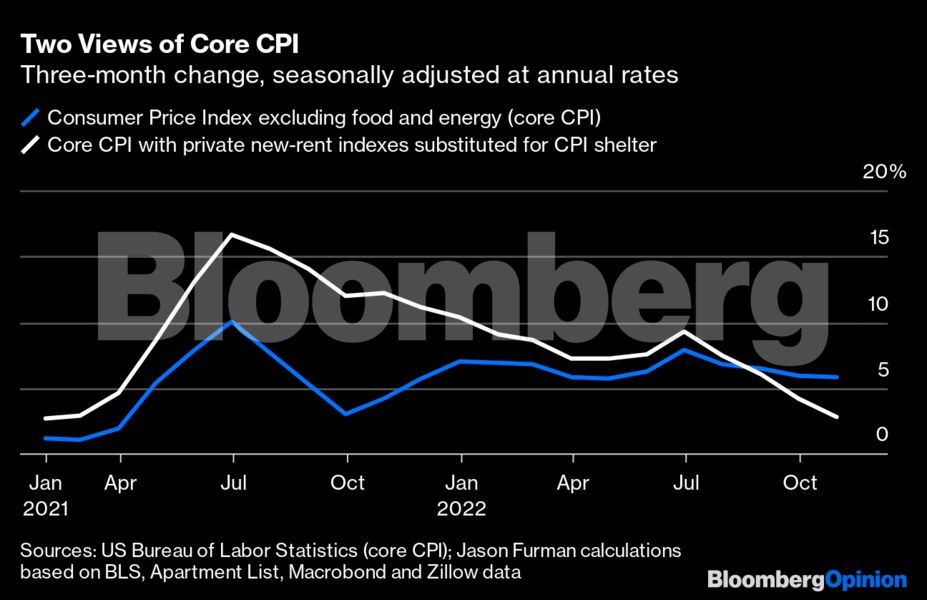

Fed officials can, of course, see what’s going on with the private rent indexes, of which CoreLogic’s has most closely approximated the movements of the new-tenant index presented in the BLS paper. They can even look at the adjusted measure of CPI minus food and energy — known as core CPI — that Harvard’s Jason Furman, a chairman of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, has started compiling monthly from the Apartment List and Zillow rent indexes and posting on Twitter.

Still, one has to think that monetary policymakers would pay closer attention if these measures were part of the official inflation statistics, and the October BLS paper seemed to represent a trial balloon for that. In his dissertation, Ozimek presented a case for actually changing the owner’s equivalent rent component of CPI, but that seems highly unlikely to happen given how much volatility it could add to the index. The CPI is used for many other purposes besides shaping monetary policy, including setting Social Security benefit levels and tax brackets, and in the early 1980s the need to keep such inflation adjustments from jumping around too much was cited frequently as a reason for changing the measure of housing costs in CPI to owner’s equivalent rent.

I ran the idea of switching to a new-leases rent measure by Princeton economist and former Fed Vice Chairman Alan Blinder, who wrote an influential paper in 1980 urging the switch to owner’s equivalent rent. “For most purposes, making that change would be a terrible idea,” he emailed in reply. “It would reflect the prices paid by a small, and not representative, minority. That said, if the BLS (or anyone) wants to create a leading indicator of inflation, using rents on new leases would be quite sensible.” Furman similarly argued that, “I don’t think they should combine that into the CPI itself but provide it as a memorandum line that people, especially monetary policymakers, can combine in whatever way they want with the other information in the CPI.” So maybe presenting it as alternative measure would be best. But it would be great if the BLS could start doing so before the Fed makes another mistake.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

To contact the author of this story: Justin Fox at [email protected]

© 2022 Bloomberg L.P.

[ad_2]

Source link