[ad_1]

Lex Populi is a new FT Money column from Lex, the FT’s daily commentary service on global capital. Lex Populi aims to offer fresh insights to seasoned private investors while demystifying financial analysis for newcomers. Lexfeedback@ft.com

Early morning mist has created pretty views of the City and Canary Wharf recently. Listed real estate is an equally foggy landscape. Performance metrics are confusing. High sensitivity to the struggling British economy often drives returns more than managerial skill. But private investors with good timing can still make money.

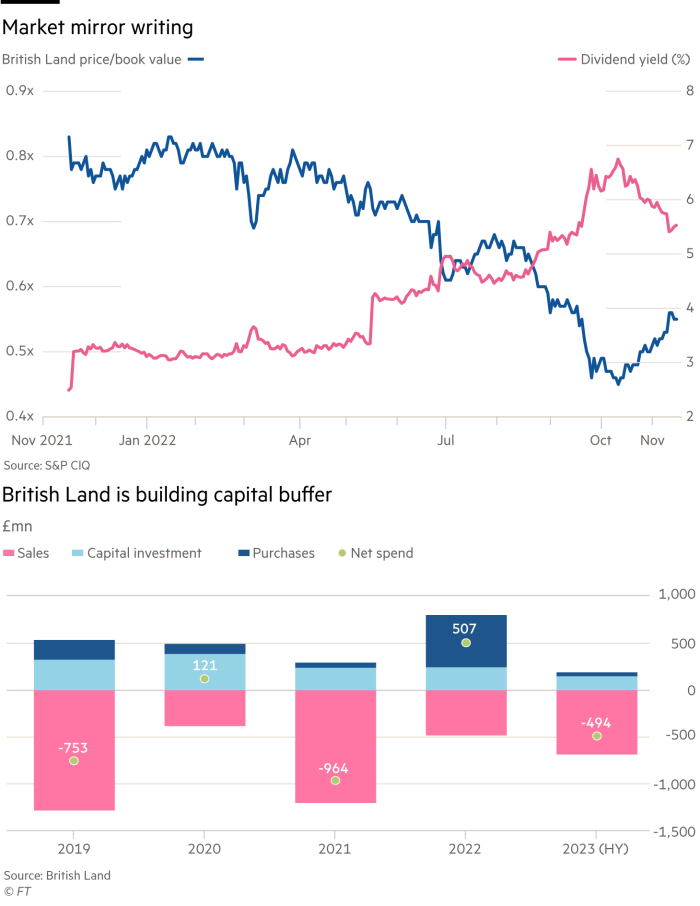

British Land and Landsec have diverse portfolios of offices, shops and other premises. The pair are therefore good proxies for the UK commercial property sector. Both reported half-year numbers this week. But statutory profits — the straw we often cling to when assessing the performance of mature businesses — can be misleading in the property sector. British Land and Landsec reported losses of £22mn and £192mn respectively.

Rather than bleeding cash, they were simply offsetting rents paid in real money with paper reductions in property prices. The more useful figures in the latter case are tangible net asset values. These fell 4.4 per cent to £6.95 per share at British Land and 5 per cent to £10.10 per share at Land Securities, compared with the first half of 2021.

That implies rental yields of some 4.6 per cent, according to Peter Papadakos of Green Street, a research business. When property values fall, yields rise: in recent open market transactions, yields have exceeded 5.5 per cent. They have been rising to stay ahead of risk-free interest rates, represented by a 10-year gilt yield currently at 3.3 per cent.

It is a reasonable bet that the two businesses will end up marking down their huge portfolios further.

That assumption is probably already baked into the shares. These trade at discounts of around two-fifths to asset values, levels last seen in the depths of the pandemic.

Bosses such as British Land’s Simon Carter make an eloquent case for the superior quality of their portfolios and their capacity to increase rents even in tough times. Those could be reasons to buy property shares at the bottom.

However, Lex takes a bearish, top-down view. We think the current rally in stock markets is narrowly based and interest rates are set to rise further, bringing more economic disruption. Real estate stocks zoom up in an economic recovery. Find broader evidence for one before investing.

Walmart: living the LIFO

Same-store sales, margins, inventory levels — these are some of the benchmarks that investors in US retail stocks scrutinise. These days, they must also get to grips with LIFO, FIFO and COGS.

An alphabet soup of inventory accounting terms is sploshing around. Sputtering consumer confidence can leave shopkeepers with big writedowns on goods they cannot sell. Next week’s Black Friday salesfest is the latest test of nerves for retailers and their backers.

Walmart gave a foretaste on Tuesday. The $400bn US retail giant said it expected LIFO charges to shave $1bn off its gross profit for next year. The disclosure — made during a call with analysts — came after the company delivered better than expected third-quarter results and said earnings this year would not fall by as much as feared.

LIFO stands for “last in first out”. Under LIFO, companies assume goods they sell first are the newest in inventories. In a high-inflation environment, newer goods cost more than older ones. LIFO means the cost of goods sold (COGS) will be higher, reducing profits.

FIFO is the alternative version of reality. It stands for “first in first out”. This accounting method, commonly used by sellers of perishable goods, assumes companies draw down older inventory first, meaning older, cheaper goods get expensed as COGS.

About 15 per cent of companies in the S&P 500 index used LIFO as their primary inventory method and half used FIFO last year, according to Credit Suisse. The rest used an average-cost method, which is a weighted average of all inventory purchased over a certain period of time, or methods that could not be determined.

Walmart generated $147bn in gross profit last year. The $1bn LIFO hit is therefore marginal. Still, understanding how LIFO works helps put inventory and margin numbers in perspective. Walmart said on Tuesday it had “significantly improved” its inventory position in the third quarter. This stood at $64.7bn at the end of October. That is up from $57.5bn a year ago.

During inflationary periods, there are fewer inventory writedowns under LIFO than when other methods are applied, accounting experts say. That reduces potential shocks to investors. But it does not absolve retailers such as Walmart from their responsibility to anticipate trends intelligently and manage stock leanly.

Lex remains a fan of the business, a standout survivor of an ugly shakeout in US physical retailing. Walmart has made a return of 62 per cent over five years, compared with 42 per cent for Amazon. The group’s value proposition, strong franchise and good online progress inspire continued confidence.

[ad_2]

Source link