In 1868, the Foreign & Colonial investment trust wooed London savers with the novel idea of investing in a diversified portfolio of international securities.

A century and a half later, the frontier spirit of investment trusts was on display again in the nondescript function rooms of a west London hotel.

In addition to free jelly beans, the several hundred investors attending the “showcase” conference of investment companies last month were enticed by the opportunity to buy into assets ranging from rock stars’ back catalogues to Kazakh banks, and from ocean-going cargo ships to private equity buyout funds.

Against the backdrop of this year’s gloomy markets, the buffet of exotic assets could easily look like a legacy of the age of low yields and easy money, when it was easy to tempt exuberant investors.

But investment managers are betting that the special characteristics of the British investment trust — an investment vehicle structured as a publicly traded company that is rare elsewhere in the world — can help them weather the storms now hitting the markets.

One key merit dating back to the trusts’ Victorian origins is the ability to hold illiquid assets within a company that allows investors to buy and sell shares daily in a liquid market. Crucially, the managers don’t have to sell the underlying assets if investors sell the trust company — as they do with investment funds.

The willingness of retail investors to turn out in large numbers for the west London conference highlights how much confidence they still have in trusts. In this FT Money special edition, we look at what trusts offer savers at a time when inflation and recession fears are stalking the global economy and rising interest rates are putting pressure on asset prices.

As well as trusts specialising in alternative investments — ranging from private equity to wind farms — we will look at trusts focused on more mainstream assets, on generating income and mitigating inflation.

“Investors are asking themselves: what differentiates this?” says Claire Dwyer, head of investment companies at Fidelity International. “Whether it’s a niche asset class or the niche take on the same investment universe, that’s what people want.”

An appetite for income

As liquidity drains away, many esoteric investment sectors could face a painful correction. Meanwhile, higher bond yields give investors more options to earn income.

“Income paying has been one of the attractions [of alternative assets]. Now, you can go and get a gilt or a cash account,” says Will Ellis, head of specialist funds at Invesco.

Many alternatives trusts — or “alts” — have swung to heavy discounts as investors turn pessimistic. Doomsayers see the falls as a portent of more pain to come.

For alt enthusiasts, undervalued trusts look like an opportunity. Even with traditional sources of income-like bonds coming back into play, plenty of managers still expect the rise of alternatives to continue, though with a shift in emphasis towards inflation-protected income from assets like infrastructure and long-term property holdings.

“We are likely to see higher levels of inflation permanently. That’s going to mean people are going to have to think harder about the level of income that you need,” says Dwyer.

“I think alts are absolutely here to stay and it’s going to accelerate. Across the industry, everything is about the private markets.”

Rise of ‘alts’

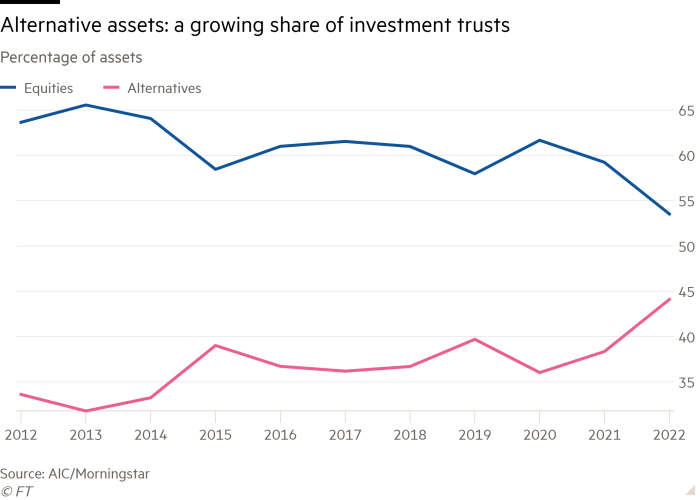

Alternatives have grown from £32bn, a third of investment trust assets, a decade ago to £116bn, or 45 per cent, this year, according to the sector’s trade body the Association of Investment Companies (AIC), while equities have slipped from two-thirds of industry assets to just over half.

As alternative assets have boomed, trusts offering more traditional stock portfolios, for some in the industry, have appeared less relevant. Broad equities strategists face constant pressure to prove their worth in the face of competition from lower-cost mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs).

“It is almost impossible to launch a conventional equity trust. The only real launches have been around alternatives, or essentially illiquid assets,” says James Budden, head of distribution at Baillie Gifford, the largest trust manager with £25bn under management across 13 trusts.

Open-ended funds are simpler, he says, “are probably more accessible and understood by buyers”.

Do-it-yourself investors also face new challenges in today’s markets — under the banner of “alts” are numerous subsectors each with their own complexities, some of which analysts warn could suffer in an economic downturn.

“The more niche you become the more risk aware you need to be and the more understanding you need to have of what the product is,” says Simon Crinage, head of investment trusts at JPMorgan.

The eclectic range of assets now on sale in investment trusts reflects the explosive growth of alternatives across the investment industry. Morgan Stanley reports that so-called “private capital” — a category including private equity, infrastructure, real estate and private credit — has expanded from less than $1tn in global assets in 2000 to about $8tn at the end of last year.

As markets shifted from last year’s cheerfulness to a downbeat mood, some analysts now think the surge in yields on bonds and cash could challenge alternatives.

Others see opportunities in alternative assets offering income with inflation protection. “Investors have been looking for alternative income,” says Melissa Gallagher, head of investment trusts at BlackRock.

Glimmers of growth

In a buoyant market for investment trust fundraising in 2021, growth capital strategies were among the most popular. These managers — such the team at Jupiter’s Chrysalis trust — invest in private companies that are beyond the venture capital stage but not yet fully mature. They aim at sectors like tech and even space as with the Seraphim Space investment trust launched last year.

Amid a general widening of discounts across the whole investment trust sector, growth capital trusts as well as private equity groups on average have swung from premiums a year ago to discounts wider than 30 per cent — a high over at least five years — reflecting investor caution about asset prices.

A few alternative sectors have been relatively more resilient, notably infrastructure trusts. Inflation-conscious investors favour parts of the infrastructure sector where assets generate revenue streams that can be tied to inflation-linked price rises, such as toll roads.

Rents on property are another alternative income stream that tend to keep pace with inflation. But some investors feel pessimistic about property trusts given predictions that real estate prices will fall in the short term, and their discounts have widened.

“Clearly, the demand for income is a big one, but linked to that is alternative sources of income rather than just bonds and equities,” says Crinage. “Just like you want a diversified portfolio, you want income from different sources.”

Jonathan Black, a retired career coach from Manchester who invests in several trusts, said he prefers trusts for accessing assets such as property, where a number of standard funds have recently had to halt withdrawals and commence fire sales of assets because too many investors wanted their money back at once. “I don’t like [it] when you try to sell and they lock you down,” says Black.

Even trusts that traditionally invest in stocks have increasingly taken to investing in illiquid assets by holding more shares in private companies.

Scottish Mortgage, known for its bold bets on high-growth companies such as Tesla, now devotes up to 30 per cent of its portfolio to private companies. As many companies wait longer before going public, trusts with similar strategies have increasingly looked to get in early by backing companies before their initial public offering.

Budden says the private company exposure helps differentiate these trusts from the equivalent funds: “You are giving people a reason to invest that you can’t find elsewhere. That is the key.”

Honing the pitch

Trusts need to seek this extra appeal in part because the roughly £260bn trust market remains niche compared to the £1.3tn UK mutual funds industry and the massive market for ETFs. For most investors, funds are the first port of call.

Appealing directly to do-it-yourself fund buyers is all the more important as wealth managers, key shareholders of investment trusts, have gradually retreated.

Research by consulting firm Warhorse Partners studying two-thirds of the investment trust sector shows City stalwarts like Rathbones, RBC Brewin Dolphin and Investec steadily owning an ever-smaller share of the trust market.

“Every year, we are seeing a tick down of 1 per cent. That doesn’t sound like too much by itself, but it’s £1bn or £2bn, which is quite meaty,” says Piers Currie, partner at Warhorse.

Wealth managers have stepped back in part because their industry is consolidating, leaving fewer larger players which have centralised investment teams.

As wealth managers increasingly see trusts as a means to invest in alternatives and dial back their exposure, DIY investors have taken up the slack, stepping in to buy trusts in increasing force.

The top three execution-only platforms — Hargreaves Lansdown, Interactive Investor and AJ Bell — together held 3.4 per cent of investment trust shares on behalf of their clients in 2022. Last year, the portion of trusts held on the three platforms had shot up to 18 per cent.

Retail investors are now the largest category of trust owner, holding 33 per cent at the end of last year.

Pree, a 32-year-old dentist, turned up at the AIC’s showcase event last month because, after parking his money with the robo-adviser Nutmeg for some years, he was considering a more sophisticated strategy using trusts.

“You can get exposure to more assets and markets,” he said. But the hundreds of trusts available made it hard to get started. “The choice for what you can invest in can be quite confusing. It’s daunting,” Pree said.

Trust managers are keenly aware that it is hard to stand out from the crowd. For many, highlighting a specialist alternatives strategy or the ability to invest in private companies has been the path to appealing to retail investors.

“The consumerisation of investment trusts is leading to a need to say: what do you stand for and why are you here . . . If it’s not clear in five or six words, people do not want to spend time trying to figure it out,” says Currie.

Advice for investors

Savers need to be attuned to the risks. Fund managers looking to make a splash may cook up ever more niche investment themes, but retail investors need to focus on what suits their portfolio rather than the latest trends. “I’ve known quite a lot of fund managers who thought risk was spelt R.E.W.A.R.D,” says Arthur Copple, chair of Temple Bar investment trust.

Alternatives should remain a small allocation and investors need to make sure they understand the risks. “Music royalties and wind farms. Where does that sit in a private investor’s portfolio? I would suggest it sits right at the edge of it,” says Budden.

John Moore, senior investment manager at wealth manager RBC Brewin Dolphin, says investors shouldn’t stretch themselves across too many different strategies, since each takes time to understand.

“Alternatives are really rewarding but they are really hard work,” says Moore. He says investors should try to understand when different alternatives will do well or suffer losses. “When the bad news comes, is this in line with what I expected or does this challenge why I am here?” he says.

Investors should also look at the shareholder registers of the trusts, since the ownership base can make a difference to how their investment will pan out. Currie says that before buying into a trust, investors should ask: “Is the village that you’re going to join in a good state of health?”

Danger arises when large chunks of the trust are owned by one or two investors. If they sell out, shares in the trust could swing to a large discount, hurting the value of others’ holdings.

Smaller trusts — those worth under £200mn — are more likely to be vulnerable. They often won’t have enough liquidity to attract larger investors like wealth managers. “There are an awful lot of equity investment trusts that are frankly subscale,” says Copple.

Trusts stuck on a large discount often become targets for mergers, which have become more common as trusts try to achieve substantial scale. These deals can be rewarding for shareholders, but that is not something investors can count on.

Boards often face pressure to control discounts by buying back shares. This can be positive, but it can also create a downward spiral if the buybacks cause the trust to shrink and make it less appealing to new investors.

If investors wait too long, it can become difficult to sell out. “If you are stuck in one of these shrinking investment trusts, you might find that the liquidity gets worse and worse,” says Copple.

The good news for trust investors is that, unlike in standard funds, underperformers are not usually allowed to carry on for too long. Trusts, unlike funds, have independent boards that will generally take action.

“The popularity of trusts is very easy to see. A consistent, long-term discount then brings into question the viability of that investment. I think boards more and more are attuned to this and they will take action,” says Budden. “The investment trust sector is incredibly Darwinian.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.