[ad_1]

One of the consequences of the financial crisis that gets little airplay these days is the slow extinction of fund-of-hedge funds. They’re not dead yet of course (there’s still about $644bn in them), but it’s pretty much the only corner of the investment industry that has flatlined or shrunk over the past decade.

Fund of funds made make an alluring promise to investors. For a fee, they find the finest hedge fund managers on the planet, combine them into a diversified, uncorrelated and high-returning portfolio, monitor their performance and occasionally cull the weakest from the herd.

In reality, in many cases it is simply another fat layer of fees over a compensation scheme masquerading as an asset class, which has ended up producing dismal results. That several big funds-of-funds invested in Bernard Madoff’s Ponzi scheme hammered home how feckless some of them were, and soured a generation of investors against the vehicles.

However, the basic model outlined above will sound familiar to some Alphaville readers, as this is pretty much the model of “multi-strategy” hedge funds like Millennium, Citadel, Point72, Balyasny or Schonfeld.

I’m not quite ready to die on this hill, but I reckon that multistrats should essentially be seen as a souped-up, better version of old-school fund-of-funds. They will eventually supplant them completely — and could ultimately dominate the hedge fund industry as a whole.

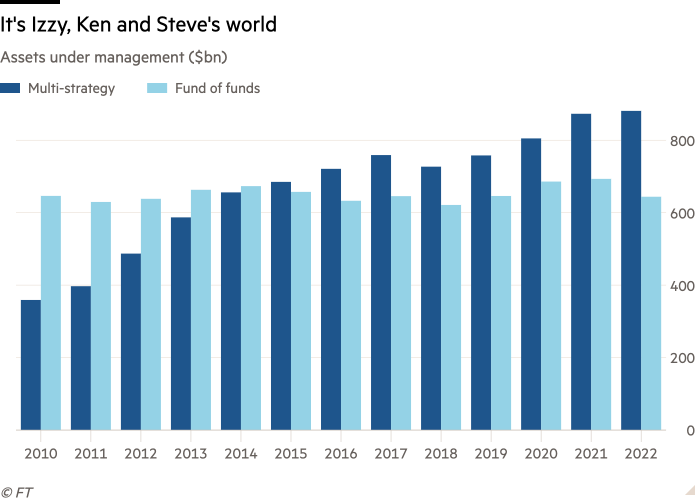

To be honest, they already have eclipsed funds-of-funds. HFR’s data indicates that the assets under management of multi-strategy hedge funds have comfortably vaulted above stagnating FoFs in recent years.

With assets under management of about $890bn, multi-strategy hedge funds are now bigger than standalone global macro funds (ca $607bn if you strip out multistrats that do macro) and approaching the roughly $1tn size of the classic equity hedge fund industry, according to HFR’s data.

Unlike traditional long-short equity funds — like the famed Tiger cubs that came out of Julian Robertson’s Tiger Management — multistrats have a horde of portfolio managers, traders and analysts that pursue a wide variety of strategies and operate in semi-autonomous units inside the mother ship. (That’s why they’re sometimes also called “multi-manager” hedge funds.)

They can do anything from M&A arb, commodities, systematic trend-following, index rebalancing trades, global macro, long-short equities, or fixed income relative value. Basically the whole menu of potential hedge fund strategies, all combined with a cherry on top.

The advantage is that some strategies that struggle as standalone funds can be added in for an overall better result. For example, a dedicated short selling hedge fund can be tricky to scale as an independent firm, but can be a great source of diversified returns as a sleeve in a broader one.

Risk is managed for each unit, and centrally by the firm itself. Even for hedge funds, multistrats are fabled for their brutal Darwinism. If you do well you get more money from the central pool to manage, and if you do poorly your allocation gets cut. And if you do very poorly, then you’re out faster than you can say “mayo”.

So far this year, multistrat funds are the second-best performing major hedge fund style, according to Aurum, only surpassed by quant funds (where we suspect results are heavily skewed by systematic trend-followers like Systematica that have been minting it this year).

Of course, there’s a fair bit of variety in the results. To take some examples we’ve seen in the press and investor documents lately, Citadel, Millennium, and Brummer are up 29 per cent, 9.7 per cent, and 15.3 per cent respectively this year through September, Weiss Multi-Strategy was flat by the end of August, while Sculptor Capital (formerly known as Och-Ziff) was down over 10 per cent.

Funds-of-funds are infamous for their extra layer of fees, but multi-strategy funds are similarly notorious for their own typical cost structure, known as a “pass-through” fee model.

In lieu of the typical 2 per cent annual management fee many simply pass every single expense — whether rents, Bloomberg terminals, server costs, salaries, bonuses and even client entertainment — on to their investors. Often this can end up being 3-10 per cent of assets a year, on top of the 20-30 per cent of any profits they take.

This is unusual in an industry where average fees have grudgingly been heading downwards for a while.

Hefty pass-through fees can be quite a big turn-off for some investors and the hedge fund consultants that act as their money conduits.

FTAV also suspects that their breadth means they actually sit a little awkwardly in a some institutional investor’s overall portfolio. Most investors like to try to fine-tune their allocations by asset classes, factors, styles etc, but multistrats can defy categorisation. Many fund-of-funds probably have the same issue today.

However, the pass-through model is an advantage when it comes to attracting entire teams of top traders. These days you can basically set up a quasi-independent hedge fund under the umbrella of a multistrat and not have to worry about the non-investing side at all.

And in reality, there are few major institutional investors in the world that wouldn’t kill for a fatter allocation to the flagship funds of Citadel or Millennium.

Their long-terms are the stuff of legend, but most of the biggest and best-performing funds are closed to new money, and typically return most of their annual gains to investors to control their size and optimise their gains. That means money sloshes over elsewhere in the multistrat world.

But I suspect that one of the biggest reasons why there is still a lot of money left in funds-of-funds — aside from classic inertia — is simply that pretty much all the top-tier multi-manager funds are closed to new money. Here’s what Bloomberg wrote in a piece last year:

Across the industry, a record 1,144 hedge funds have stopped accepting new money, the most since data tracker Preqin started compiling the information. Of twenty multi-manager firms managing more than $220 billion collectively, thirteen are no longer taking in more cash, according to Julius Baer Group Ltd. Crucially, those closures are happening at some of the biggest and sought-after firms.

So why am I making this long-winded argument about multi-strategy hedge funds and FoFs? It’s just something I’ve been thinking about as a mental model to explain to myself the exploding popularity of multistrats (beyond the juicy returns of some of the top funds).

Thoroughly analysing portfolio managers, judging how much capital their strategies can optimally manage, constantly monitoring them, and firing underperformers; management is an arduous, difficult task — even before you start thinking of how to combine them into an overall portfolio.

I suspect a lot of institutional investors are realistically not up to it, but they intuitively liked the fund-of-funds model, and now love the multistrat model.

After all, who wouldn’t want Steve Cohen, Izzy Englander, or Ken Griffin to oversee their hedge fund portfolio? And if you can’t get one of them, then the second- and third-tier multi-manager funds are still likely to do better than most FoFs. The question is whether they’ll still be worth it, or if they’re merely benefiting of the lustre of the top dogs.

[ad_2]

Source link