[ad_1]

This article is the latest part of the FT’s Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign

Sarah Johnston is “sick with worry”. A 43-year-old teacher in East Yorkshire, she and her husband, a long-serving police officer, will face the full force of the mortgage shock next year, when they come to refinance borrowing on their “forever home”.

In May 2021 they took out a £315,000 mortgage on the £395,000 house under a two-year fixed-rate deal at 1.99 per cent. Their plan was to remortgage in 2023 after making improvements to the four-bedroom home and hoping the work would lift the value of the house, thereby giving them access to better mortgage rates.

That strategy now lies in tatters. As mortgage rates have soared, the couple, who have a nine-year-old daughter, are looking at paying £640 more a month for another two-year fix from 2023, on top of their current £1,480 monthly bill.

Johnston is daunted by the extra expense, alongside additional costs of at least £2,000 a year on her energy costs from April next year, following new limits on government help for household energy bills. “Between the energy rises and the mortgage we’re probably looking at £800 a month extra,” she says.

The mortgage crunch has hit households across the country, as lenders have hoisted borrowing rates in response to rate rises at the Bank of England and the market turmoil unleashed by the government’s “mini” Budget in September.

Consumer prices rose by a 40-year high of 10.1 per cent in September. The BoE has warned the UK faces the worst squeeze in living standards for 60 years. Mortgages are just one pressure point, along with steep rises in energy bills and food and drink prices.

The great majority of borrowers are on fixed-rate deals, offering them protection from rate movements for the period of the fix. But with markets expecting base rates to hit 5 per cent or more next year, many who need to refinance over the next 18 months will face much higher bills.

The promise of a new government with a more orthodox approach to economic policymaking has improved the outlook for mortgage holders. But in his first address as prime minister, Rishi Sunak this week warned the UK was in “a profound economic crisis” and the pressures on people’s personal finances remain formidable. FT Money looks at the changing options for borrowers in a world of unenviable mortgage choices.

The end of cheap borrowing

Mortgage rates began their upward path in December last year, in step with successive rises to Bank of England base rates. But their trajectory steepened after former chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s “mini” Budget triggered a backlash on bond markets and a surge in gilt yields — which influence mortgage pricing.

Two-year fixed-rate deals now carry higher interest rates than five-year, or — cheaper still — 10-year fixes, in a reversal of the pricing relationship that has held over the past decade. The average interest rate on a fixed two-year mortgage on Thursday was 6.49 per cent, or 6.35 per cent on a five-year deal, according to finance data provider Moneyfacts. The 10-year average is far lower, at 5.63 per cent.

Only 12 months ago, average two-year rates were 2.25 per cent; or 2.55 per cent for five-year deals.

Recent days have brought a glimmer of hope for borrowers watching these increases with fear and trepidation. Their pace has slowed as the government reversed most of its planned tax cuts; markets this week sent gilt yields back to levels seen before the “mini” Budget.

Eleanor Williams, finance expert at Moneyfacts, says: “The level of product choice available to borrowers is fluctuating as lenders review their offerings and try to keep up with an evolving economic outlook.”

As conditions have calmed, some lenders have begun cutting rates: Santander on Tuesday said it was taking up to half a percentage point off rates for new customers on fixed-rate mortgages. Chris Sykes of broker Private Finance says: “We are starting to see a couple of rate reductions in the last few days from Accord, HSBC and Coventry with a new introduction of rates, and we suspect a few others will follow, albeit very, very slowly, reacting to demand levels.”

But he adds that lenders are likely to resist a wholesale move to cheaper rates until at least November 3, when the Bank of England is expected to hand down its next rate rise in the battle against inflation.

Fix or track

In recent weeks many have rushed to secure a fixed rate before the lender removed or raised it. Victoria Wood, who is expecting a baby in two months, says the uncertainty around mortgage rates has been “terrifying”. She and her husband, who live near Stockport, Greater Manchester, were contemplating a sharp rise in their 2.75 per cent deal on a £280,000 mortgage with Halifax in March 2023, when their fix was due to end.

Seeing rates rising by the day, she decided to act. The best deals she could get via a broker were at 6 or 7 per cent — raising the couple’s monthly costs by £600 — but Halifax was offering a product transfer at 4.37 per cent on a five-year deal. The catch was the couple would have to pay a £2,800 early repayment charge to get out of the previous mortgage.

The attraction of certainty won out and they took the in-house deal, in spite of the penalty payment. “I need to know what’s going on and the sleepless nights and stress are not good . . . At least now we know what’s going to happen for the next five years and we can budget,” she says.

Those considering doing the same thing now, however, will be locking into long-term deals at 5.5 or 6 per cent. If more lenders continue to reduce mortgage rates and hold them there, borrowers could be paying more than they need.

One way of managing this uncertainty is by taking a variable rate deal — a type of mortgage that has re-emerged as a viable option as rates jumped. There are two chief types: trackers, linked to the Bank of England base rate; and discounted variable rates, which offer a discount for a set period on a lender’s standard variable rate (currently averaging at 5.63 per cent, according to Moneyfacts).

By definition, these rates can move up or down, so demand a stronger stomach for risk than their fixed-rate cousins — but the lower headline rates carry considerable appeal in the current climate, says Adrian Anderson, broker at Anderson Harris.

“A lot of people I’m talking to want to consider a tracker or a discounted rate — ideally something that has no penalties [for switching out early]. If fixed rates start to come down next year they could jump back on to one and not be tied into a rate that begins with a 6.”

Beverley Building Society is offering a two-year discounted variable rate at 2.57 per cent, with a £995 fee and a minimum deposit of 20 per cent. Moneyfacts puts the average two-year tracker at 3.69 per cent across all LTVs.

In spite of the difference in headline rates, Anderson says it is not always easy to decide between a tracker and a discounted variable rate. But the tracker, which is pegged to the BoE base rate, is marginally more predictable, compared with a lender’s standard variable rate, which may or may not respond to base rate changes.

Buying and selling

How has the mortgage maelstrom fed through to the property market? One effect is that cash buyers have the whip hand as sellers are more likely to favour purchasers who can sidestep the current uncertainties over mortgage offers and rates.

“There is no doubt that if you are a cash buyer, you are a much simpler, much more predictable and highly bankable commodity,” says Henry Pryor, an independent buying agent. “Estate agents and their clients are very, very keen on cash buyers or the next best thing — buyers who got their finances organised prior to, say, September 23 [the date of the “mini” Budget].”

Pay down or offset?

To those with spare cash, paying off the mortgage might seem the obvious answer amid soaring rates. But Adrian Anderson, director at broker Anderson Harris, notes that higher earners are keeping a borrowing facility on hand via an offset mortgage.

Offset providers typically offer a tracker or fixed rate deal to those who simultaneously put cash into a current account with that lender — money which “offsets” the interest charged on the mortgage debt. “If you have, say, £800,000 in a current account with a lender and £800,000 as a mortgage, they net each other out,” Anderson says.

“If they’ve got the ability to offset the mortgage, it’s almost like completely repaying your mortgage, but actually you’ve still got access to liquidity.”

For those buying with a mortgage, Pryor warns that playing clever with sellers by chipping away at the price — without checking the small print of the mortgage offer — could create unforeseen risks.

“If you have a formal mortgage offer on a house and you renegotiate the price, the mortgage offer almost invariably includes a clause that allows the lender, if they wish, to vary the terms of the mortgage,” he says.

He cites one buyer who recently secured a price cut of £20,000. Had the mortgage lender taken up their right to change the terms — and applied its current rates of interest — the buyer would have faced an extra £200,000 in mortgage costs. “You’ve got to be very, very careful,” he says.

Mortgage availability is a key determinant of house price movements, but there remains wide variation among economists over the outlook for the housing market, given imponderables such as the duration and depth of a recession, the impact on employment and the persistence of inflation. Lloyds Banking Group, the UK’s biggest mortgage lender, on Thursday said it expected house prices to fall by around 8 per cent next year.

Richard Donnell, research director at property website Zoopla, says that if mortgage rates were to fall to 4 per cent next year, the market would be relatively unaffected. But 5 per cent fixed rates are “a tipping point”.

“If we stay at around 5 per cent, then we’ll see a few percentage points off prices in London and the Southeast, but the whole market will be roughly OK,” he says. “But if we stay at 6 per cent mortgage rates for the whole of next year, we probably are looking at falls of 10 per cent.”

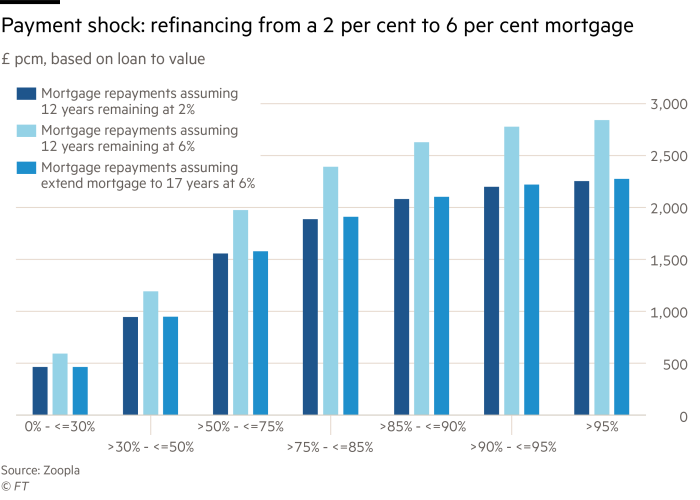

Extending the term of a mortgage may be the best way for borrowers to ride out elevated rates expected in the months ahead, he suggests. A typical borrower coming off a two-year fix at 2 per cent and facing a new rate of 6 per cent will face extra costs of £400-£500 a month.

With an average 12 years left on their loan, though, if such a borrower were to extend the term by five years to 17 years, the savings in monthly repayments would cancel out the rate increase. “The payment shock today is minimal,” he says, “but you will end up paying much more in interest.”

First-time buyer: fear of negative equity

Lloyd Brown, a first-time buyer in south Wales aged 32, has been trying to buy his first home for several months.

A lecturer in law at Swansea university, he had his eye on an attractive semi-detached Victorian home earlier this year until discovering the three-bedroom house had been underpinned. He came close to buying a second option, a three-bed terraced house at £160,000, but realised it was a relatively high price for a home riddled with damp.

Pulling out in the week of the “mini” Budget, he now finds mortgage rates have risen even higher. For now he will live with his parents, paying a monthly rent. And instead of keeping his savings on hand for a housing deposit, he is “weathering the storm” by placing them in a two-year fixed rate Isa.

“As a singleton I personally would be worried about the risk of negative equity and the demands of paying such high rates on my own,” he says.

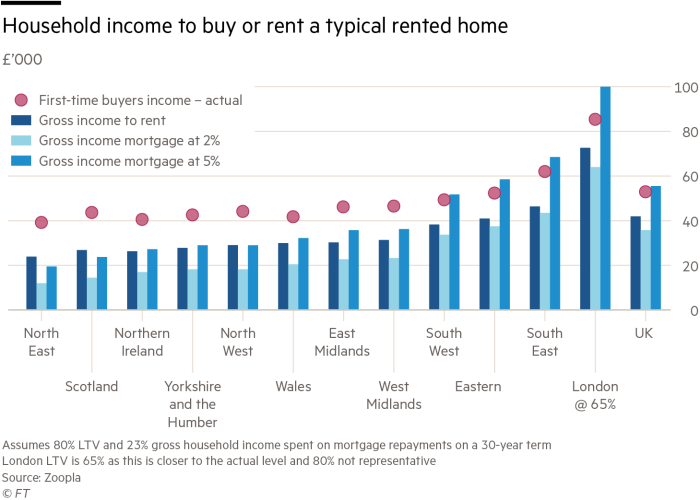

Brown’s experience underlines a trend identified by Richard Donnell, research director at Zoopla, for first-time buyers outside the expensive regions of London and the Southeast “to buy bigger homes than they need, not the homes they rent”.

With mortgage rates at 5 per cent, he calculates, monthly mortgage repayments are cheaper than renting in many areas outside the south of England. In recent years these buyers have been eschewing smaller flats in favour of larger two- or three-bed houses.

But it is unclear whether the trend will continue, he says. “The question is, will first-time buyers now want to keep buying but down-trade or will they wait until they can afford a three-bed again?” Brown, for one, is content to wait and see.

[ad_2]

Source link