[ad_1]

Investors have in the past month been watching the dramatic moves in the UK government bond market with as much fascination and dread as a horror show: what for years has been seen as a tame house cat has bared its claws and turned into a wild tiger.

Almost every time observers hoped the worst might be over, their screens were filled with more carnage.

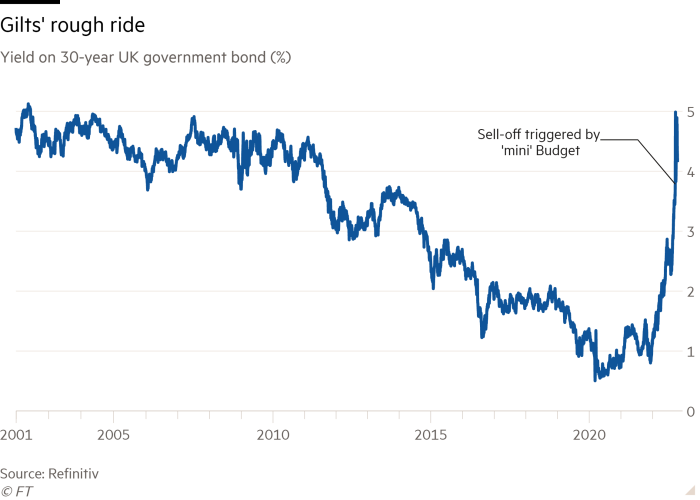

The yield on these bonds (called gilts) soared from 1.1 per cent at the start of 2022 to a peak of 4.99 per cent for the 30-year instrument, before falling back to 4.35 per cent after the Bank of England intervened, Jeremy Hunt replaced Kwasi Kwarteng as chancellor and the government’s fiscal plan was scrapped.

It was totally unexpected. Gilts had long been seen as almost as risk-free as cash. That’s why, 10 years ago when my great aunt Peggy needed to sell her home to pay for care, she put the money raised into gilts on the advice of her financial adviser. It turned out well, with Peggy having more than enough for a comfortable old age.

“For individual investors, gilts could be seen as a cash proxy, liquid and not volatile. ” says Oliver Faizallah, head of fixed income research at Charles Stanley. “Recent events have turned that on its head.”

In the short-term, investors can take comfort from the fact that Hunt’s dramatic appointment has calmed frayed City nerves. Richard Carter, head of fixed interest research at Quilter Cheviot, says: “The market will have been craving a safe pair of hands to guide the UK through this difficult period . . . .How long he gets to do this for will ultimately be the next question.”

In the longer term, the effects are more complex. On the one hand, gilts’ reputation as a safe investment has been damaged — the huge upswing in yields has cut the capital value of the bonds investors hold. Anybody selling a 30-year-bond they bought at the start of 2022 would be looking at a capital loss of more than 40 per cent. They won’t forget that in a hurry. As Susannah Streeter, senior investment and markets analyst with Hargreaves Lansdown, says: “What has become clear is that bonds cannot be seen an ultra-safe haven, particularly in times of high market nervousness.’’

On the other hand, for new investors, or those wanting to increase their bond portfolio, the yields now on offer are the highest for 10 years. Certainly, they could still go higher, given the inflationary dangers in the UK and world economy. If yields went higher, bond values would fall again. But for those investors who can live with this risk — and don’t intend to sell their bonds any time soon — current yields are tempting.

They are so tempting that it is worthwhile for private investors to revisit the old question: should they keep their money in cash — as British householders overwhelmingly do — or switch some of those savings into bonds? FT Money looks at the arguments.

The risk of holding cash

Convention says that if you’re ultra-risk averse, choose cash rather than gilts.

The problem with cash is that it’s never been risk free — and it’s starting to look riskier. By holding it in the bank or building society, your money is protected by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme, which guarantees up to £85,000 per person for each institution. But you risk losing out to inflation.

Consumer Prices Index (CPI) inflation is running at 10.1 per cent, while the most you can get for your cash savings on a two-year fix is 4.77 per cent. Your emergency cash in the bank or building society is not holding its value, while retirees in drawdown, usually advised to stash away two years of basic income, face the harsh reality of their money losing spending power.

It’s possible to shelter cash in a tax-shielded individual savings account (Isa), but the rates are not so good as on conventional accounts.

It’s no wonder that investors have been exploring opportunities in gilts. Investment platform Interactive Investor reports sophisticated retail investors have been buying gilts since the start of September, following their sharp sell-off.

On Monday, after the chancellor’s statement, one of the popular gilt buys, the 5 per cent Treasury stock maturing in March 2025, yielded 4.903 per cent — a decent income for the next two and a half years that beats the top two-year fixed rate savings account.

But you need to understand what you are buying. A gilt is a bond, which is a loan. By buying the bond, the investor is lending the government money for a set time. In return, the government pays interest — called the “coupon” — as a fixed percentage of the face value and at the end of the bond’s lifespan repays the initial investment, known as the “principal”.

Don’t confuse the coupon, which is fixed and usually paid annually or semi-annually, with the bond’s yield. Bonds, just like shares, vary in price according to supply and demand. The yield varies according to the bond’s trading price — if the price rises, the yield falls and vice-versa. When gilt yields rose in relation to the Kwasi mini-budget, this was the flip side of a fall in gilt prices — investors were selling gilts because they had lost confidence in the government.

Experts say the risk of default is minimal, even allowing for the battered state of the nation’s finances. Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell, says: “The UK has not defaulted — and ceased to pay interest (the coupons) or repay the original loan upon maturity (the return of principal) since King Charles II and the Stop of Exchequer in 1672. If the worst comes to the worst, we’ll just print more money so we can repay our debts.”

However, the big risk is that gilts are sensitive to interest rates. If they rise sharply, as now, gilt prices fall and yields spike.

As a rule of thumb, the longer the maturity of a gilt, the higher the yield. This is compensation for longer term lending. However, longer lock-up periods mean more sensitivity to interest rates, known as “duration”. If rates fall investors tend to see better returns on longer-dated bonds, but they will be punished more if rates rise.

So, if you bought a gilt yielding 4.9 per cent today, you might hope that bond prices could rise, giving you capital gains. A gilt bought at £100 and sold at £105 would be a 5 per cent capital gain — in addition to the coupon income.

In the meantime, if you’re an income seeker willing to hold gilts to maturity, shorter-dated bonds look useful, and those maturing in 2024 or 2025 have been popular with retail investors. Sam Benstead, collectives specialist at Interactive Investor, says: “Holding a bond for 10 or 20 years until maturity may be unrealistic due to changing life circumstances, but locking up your cash for three years while the government pays you could be a very sensible thing to do.”

It’s also a way for investors to earn better rates than the paltry returns on cash.

Benstead says investors holding a shorter gilt to maturity should not worry about the impact of interest rates on bond prices as the principal will be returned on maturity, and interest payments will be paid along the way.

If you want to buy gilts directly, like equities, you should include them in a portfolio of bonds — diversified by issuer including governments and companies, and by maturity.

Most investors can more easily access gilts (and fixed-income more widely) via funds, tracking a basket of gilts or leaving selection to professionals.

Investment platforms recommend different trackers. Hargreaves Lansdown suggests Legal & General All Stocks Gilt Index Trust C, while Interactive Investor likes the iShares Core UK Gilts ETF and the Vanguard UK Govt Bond Index £ Acc. AJ Bell recommends three Lyxor ETFs: Lyxor FTSE Actuaries UK Gilts 0-5yr ETF, Lyxor FTSE Actuaries UK Gilts ETF, Lyxor FTSE Actuaries UK Gilts Inflation-Linked ETF.

Some of these have seen 30 per cent falls in value since late last year so may be at a good entry point.

Meanwhile, interactive investor reports some big capital preservation investment trusts, including Ruffer, Capital Gearing and Personal Assets are keen holders of index-linkers to secure a set “real” return above inflation.

An index-linked gilt adjusts the yield and final repayment to meet inflation, so that the investment retains its real or inflation adjusted value over the length of the contract. At Hargreaves Lansdown, Streeter explains: “They have been a preferred asset as prices have spiralled upwards to eye-watering levels. However, they are far from immune from the volatility which has wracked financial markets.”

Nevertheless, buying even a small return above the inflation rate might look attractive in today’s environment, particularly if you think inflation will be higher for longer. That’s something that cash no longer provides.

If the market settles down, and most markets eventually do, this could prove a buying opportunity. Faizullah says: “We believe the large dislocation across the entire gilt curve has resulted in yields that overestimate the risk of the UK.” He sees the most value in 5-10 year gilts.

Others are hanging on, believing prices will drop further as yields will go higher. Noelle Cazalis, a fund manager on the Rathbone Strategic Bond Fund. “Overall we believe the trajectory in gilt yields is more likely to be upwards from here, meaning prices will be lower,” she says. “But we will be looking to [buy] . . . once we near the peak in interest rates.”

So if you want to add some claws to your portfolio, tread carefully, and don’t add too many. If my ultra-cautious aunt Peggy were making her decisions today, I’d tell her to buy some gilts but keep a chunk in cash.

What you can get from cash

Half of Britons keep their savings at the same bank as their current account, according to Opinium research for Hargreaves Lansdown. They believe it makes things easier.

But your current account provider is unlikely to be more convenient for cash than any other bank. There is little reason to overlook unfamiliar brands if they have the same protections in place as well-known brands.

“Across the variable and fixed cash savings markets the biggest high street banks fall way behind and savers would be wise to reconsider their loyalty,” said Rachel Springall, finance expert at Moneyfacts.

First, don’t ignore your easy access account. Some still pay as little as 0.01 per cent, so be proactive and find a better deal.

Until fixed rates have peaked, it may be worth considering instant access. The top-paying easy access account is Cynergy Bank, offering 2.75 per cent. Plus, you could get £200 cashback to switch your current account to Nationwide’s deal, paying 5 per cent interest fixed for 12 months on balances up to £1,500.

Atom Bank has increased the rate on its five-year Fixed Saver to a market-leading 5 per cent.

DF Capital tops the one-year fixed rate deals, offering 4.6 per cent and Tesco Bank’s two-year savings rate tops the league at 4.77 per cent.

And now, depending on the size of your cash holding, you might find yourself paying tax on it. The Personal Savings Allowance (PSA) was introduced in April 2016 and means that for basic-rate taxpayers, the first £1,000 of savings interest is tax free. For higher-rate taxpayers it’s £500, while additional rate (45 per cent) taxpayers, do not receive a PSA at all.

When introduced, it was estimated that 95 per cent of cash savers would no longer pay any tax on interest earned on savings accounts. But that is changing rapidly as rates rise. Today, £36,364 in the best easy-access account at 2.75 per cent could breach the PSA, according to Savings Champion — that’s a dramatic change.

While the best cash Isa rates still lag behind the gross rates of the best non-Isa accounts, they have been recovering fast.

You can get 3.9 per cent on a one-year fix from Shawbrook Bank; and 4.3 per cent on a two-year fix from Kent Reliance.

This is a fast-changing scene, with good deals disappearing fast, so keep reviewing the competition on comparison sites such as Moneysavingexpert, Moneyfacts and Savings Champion.

What you need to know about gilts

UK gilts are issued with a maturity date, a coupon and a price. The maturity date and coupon are specified in the bond name, such as TREASURY 5% 07/03/2025. This gilt matures in March 2025 and the coupon pays 5 per cent interest per annum.

A gilt also has an International Securities Identification Number (ISIN), a 12-digit alphanumeric code that uniquely identifies it. For gilts, this usually starts with GB — the example here is GB0030880693. It also has a “ticker” symbol, a unique series of letters for trading — this gilt’s ticker is TR25. Gilts are usually issued at par, their face value, mostly £100. The TR25 was issued on September 27 2001.

Interest on gilts is paid gross, but is liable for income tax. This makes gilts particularly attractive to non-taxpayers. But profits from selling gilts are totally free of capital gains tax.

UK gilts are available to buy on investment platforms in chunks of as little as £100. You can hold gilts tax-efficiently in a stocks and shares Isa or in a self-invested personal pension.

[ad_2]

Source link