[ad_1]

Amid all the noise in the markets you might have missed a small news item that an eagerly-anticipated new fund launch had been “paused”.

The Sustainable Farmland Trust was due to list a couple of days ago on the London market. It would have been the first UK-listed fund investing in high-quality, highly productive US farmland.

Food continues to be in the news, but in truth anything food-related on the stock markets has had a tough time of late — despite all those worries about feeding the world. The commodity core of the food market — grains, for example — has seen prices drop back after sharp increases, while the sexy bit, foodtech, has experienced a stock market bloodbath — as I know through running a food tech blog (FutureFoodFinance).

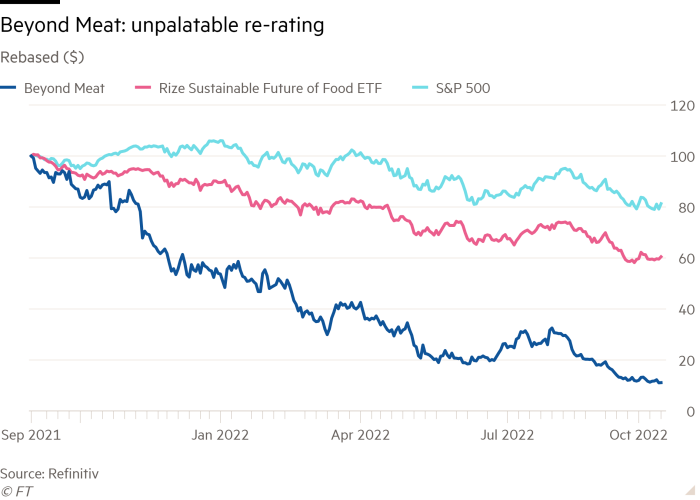

Food delivery companies, from the likes of Ocado and moving through all the Deliveroos and Just Eats, have seen their share prices massacred. A symbol of the brutal re-rating has been Beyond Meat, the doyen of all things alternative plant-based meat. Its shares have collapsed by nearly 80 per cent since the beginning of the year. It has suffered a string of “challenges” not least the departure of the chief operating officer after he was allegedly involved in a fight; and dismal take-up in fast food restaurants in the US (less so in Europe) of its fake burgers.

Not unsurprisingly, those curators of expert opinion, the global consultancies, have turned tail and admitted that maybe alternative proteins might not be such a big thing after all. As Deloitte pronounced: “The addressable market may be more limited than many thought.” Personally, I found a small news story much more interesting, namely that food giant JBS has pulled the plug on a new plant protein factory in Denver, which only opened late last year.

So if the majors are pulling the plug, does that mean it is game over for all the emerging clever food technologies?

Maybe. But I think there are some really interesting initiatives emerging that don’t cut through to a wider investor audience, what with the noise about sell-offs.

First, the centre of gravity for alternative proteins, be they plant-based or grown in a vat (cultured meat) is moving inexorably towards Asia.

Singapore is pushing ahead with new technologies and you can already buy (expensive) fast-food chicken grown in a bioreactor.

Asia has woken up to the need for new ideas and greater security in food — one recent report (by Roots Analysis) observed that annual intellectual property filings for plant-based meat has grown more than three times over the past decade, with more than half of intellectual property documents originating from Asian-based companies.

If I were looking for a future for plant-based meat alternatives it would be in China. It’s noticeable that even in cultured meat (meat grown in a lab), venture capital firms including the Aim-listed food venture capital fund Agronomics are increasingly turning their attention to Asian-based businesses.

I’d also keep a beady eye on the regulators in the US approving cultured meat-based alternatives to plant-based products — especially those involving tuna. This could come as early as next year and spark a land grab as other start-ups launch products involving other fish alternatives.

But, for me, the most interesting broad space in food is what’s called agtech, or, more specifically, vertical farming, biological alternatives to pesticides, plant biotech and seeds and farm automation.

Let’s take each in turn. US-listed AppHarvest is one of a host of businesses swarming into controlled agriculture, be that next-generation greenhouses or city-based vertical farms.

Having originally focused on high-margin leafy greens, companies are already switching to fruit (strawberries) and even tree saplings.

The Scottish government’s forestry agency recently announced that it aims to grow millions of saplings indoors before transferring them to the wild. But it’s Asia you need to watch in vertical and closed-environment farming, especially city states with little farmland — Middle Eastern cities and Singapore.

Next, the battle to replace synthetic pesticides and herbicides is speeding up, helped by governments around the world calling for action.

The big boys are already piling in: Syngenta, for instance, recently acquired Valagro, a major player in these technologies, and is now busily positioning itself in a market it reckons could hit $10bn by 2030.

Syngenta says that modern integrated pest management (IPM) strategies, which combine pheromones and other control methods with synthetic sprays, might work better. Up against these giants you’ll also find smaller players, including UK-listed Eden Research, which is also developing biopesticides.

Plant biotech is also worth a look, alongside seeds more generally. Keep an eye on US giant Corteva, spun out of Du Pont. This US business has traditionally made much of its money from corn seed but is now developing new technologies including using AI to develop plant biotech processes that allow seeds to adapt to changing climates.

Scientists have already used DeepMind, the UK-based artificial intelligence company, to engineer potatoes better suited to survive warmer climates. Sitting alongside this technology and using many of the same genetic engineering tools, is the development of biomaterials, led by businesses such as US-listed Gingko Bioworks.

The standout for me? Spider silk protein made by Spiber and AMSilk, the industry leaders, has grown in production incredibly fast since 2008, although it still totals just eight tonnes currently.

Finally, there is the inevitable automation of farms, powered increasing cost inflation, greying farm owners and inadequate supply of farm workers.

Typical of this push is the remorseless rise of robotic strawberry-picking machines which are starting to emerge in specialist farms. If you want one gauge of why this matters consider the recent announcement by US giant John Deere that it plans to go autonomous with driverless tractors and other machines. It will install huge numbers of sensors dotted around a farm, integrating information flows into big data dashboards, and then using that data to enable more automation.

Some perspective is needed — according to Deere, the global fleet of its autonomous tractors is less than 50 today but the US firm plans to have a fully autonomous farming system for row crops in place by 2030.

Finally, I think that in virtually every subsector in agtech it will be the existing big players, nearly all of which are publicly listed, that grab the dominant market share.

For the smaller companies the challenge is to scale up quickly enough, with enough cash in the bank, so they can be bought by bigger companies such as Deere and Corteva.

That also spells plenty of M&A activity that will benefit specialist venture capitalists — watch this space as agtech venture capitalists and vertical farming specialists look to list their funds on the London market once sentiment stabilises. And watch out for Sustainable Farmland Trust. I’m sure they will be back as investing in highly productive, high-quality US farmland is probably one of the safest bets in a world of higher inflation.

David Stevenson is an active private investor. Email: adventurous@ft.com. Twitter: @advinvestor

[ad_2]

Source link