[ad_1]

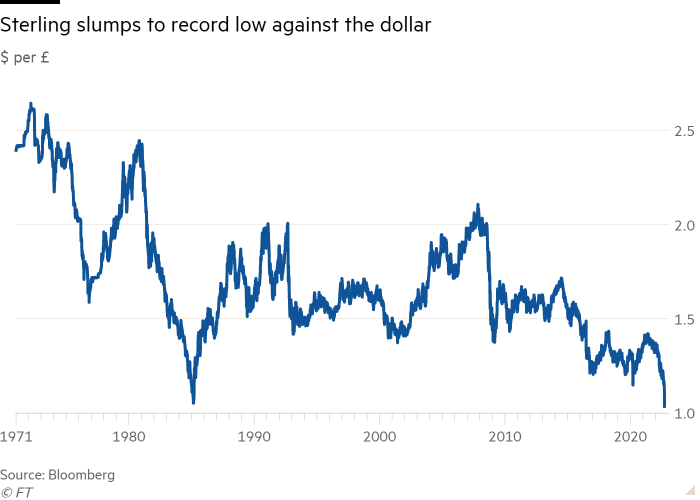

The Bank of England and UK Treasury on Monday battled to calm market turmoil after the pound hit a record low against the US dollar, but sterling suffered a fresh round of heavy selling as investors fretted over the sustainability of public finances.

On a day when the pound hit an early-morning low of $1.035, the BoE issued a statement saying it would “not hesitate to change interest rates” to keep inflation under control.

But its announcement that it did not intend to conduct a “full assessment” of the UK government’s controversial new debt-fuelled economic policy until its next scheduled meeting in November caused new concern.

The statement dashed market hopes of an emergency BoE rate rise to prop up the pound. The currency promptly dropped to under $1.07 from its high of the day of $1.0931. UK government bonds remained under heavy selling pressure. Sterling was up 0.8 per cent against the dollar in morning trading in Asia on Tuesday at $1.0773.

Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng had attempted to calm markets in a statement — co-ordinated with the BoE — in which he vowed to accelerate the development of a new strategy to bring debt under control.

Kwarteng told the Financial Times on Friday he would set out a new medium-term fiscal plan “in the new year”. Instead, he will set out the new strategy to put debt on a downward path on November 23.

He also tried to reassure markets by announcing an independent set of forecasts by the Office for Budget Responsibility on the same day; a new Budget would be held next spring.

The statements followed intense talks between Kwarteng and BoE governor Andrew Bailey in the wake of the chancellor’s new fiscal plan, which combined £45bn of tax cuts with a massive wave of new borrowing.

The bank said it would not “hesitate to change interest rates as necessary to return inflation to the 2 per cent target sustainably in the medium term, in line with its remit”.

But it added that its action would come only after “a full assessment at its next scheduled meeting of the impact on demand and inflation from the government’s announcements”.

Asked whether the UK’s new fiscal plan had increased economic uncertainty and raised the odds of a global recession, Raphael Bostic, president of the Atlanta branch of the US Federal Reserve, said: “it doesn’t help”.

The OBR’s economic predictions are expected to show underlying government debt on a persistently rising path as a result of Kwarteng’s move to put in place the largest tax cuts since 1972 and when the government’s cost of borrowing is rising sharply.

In a bid to demonstrate fiscal responsibility, the Treasury confirmed it would stick to current government spending plans — which extend beyond 2024, when the next election is expected.

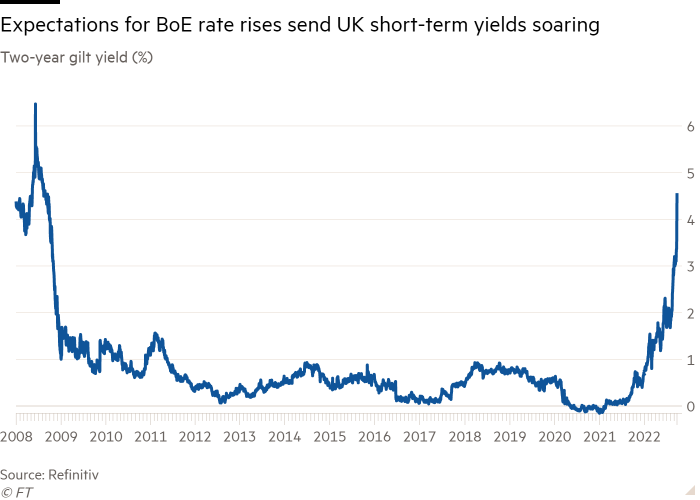

Traders unwound their bets on an unscheduled shift to higher rates but stuck by their wagers on an extra-large rise at the central bank’s next meeting. Following the BoE’s announcement, markets were pricing in a 1.5 percentage point increase to 3.75 per cent in November. The bank rate is expected to reach almost 6 per cent by May.

Trading in the pound on Monday was the most turbulent since the depths of the coronavirus crisis in 2020, with the currency recording a swing of more than 5 per cent between its high and low points on the day.

Early in the morning, the pound lost as much as 4.7 per cent to trade as low as $1.035 against the dollar after Kwarteng vowed at the weekend to stick with his tax-cutting drive.

“The UK is now in the midst of a currency crisis,” said Vasileios Gkionakis, Citigroup’s Emea head of foreign exchange strategy.

UK government debt dropped further on Monday following Friday’s bruising sell-off, the worst day for the gilt market since the early 1990s.

The 10-year gilt dropped sharply in price, pushing yields up by a sizeable 0.42 percentage points to 4.2 per cent, up from about 3.5 per cent before Friday’s fiscal announcement. Two-year yields, which are particularly sensitive to BoE expectations, have surged to 4.5 per cent, from 3 per cent at the end of August.

“It looks like we’re headed for a spiral that we usually see in emerging markets crises, where policymakers struggle to reassert credibility,” said Mansoor Mohi-uddin, chief economist at Bank of Singapore. He highlighted that the country was still running a “gaping current account deficit”.

Additional reporting by Jim Pickard in Liverpool, Stephanie Findlay and Hudson Lockett in Hong Kong, Adam Samson in New York and Leo Lewis in Tokyo

[ad_2]

Source link