[ad_1]

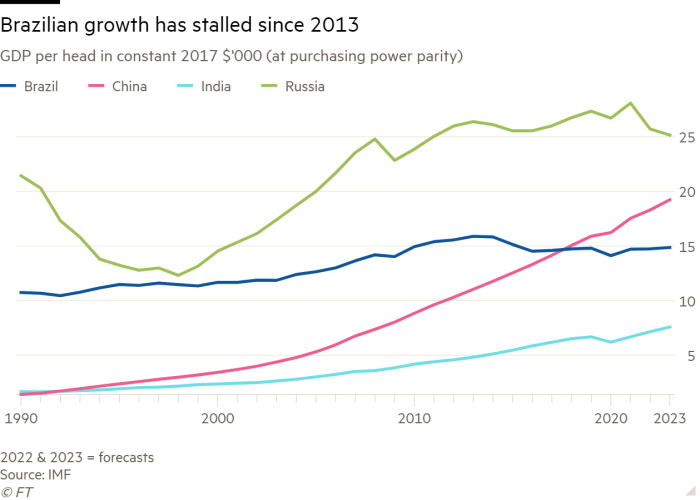

Brazil’s ascendancy in the early years of the 21st century as an emerging market darling — the B in the Brics — ended with a thud in 2014.

The nation had been riding a global commodities boom with increased exports of raw materials and foodstuffs, especially to a resource-hungry China. It then collapsed into a brutal recession from which the country has still not recovered.

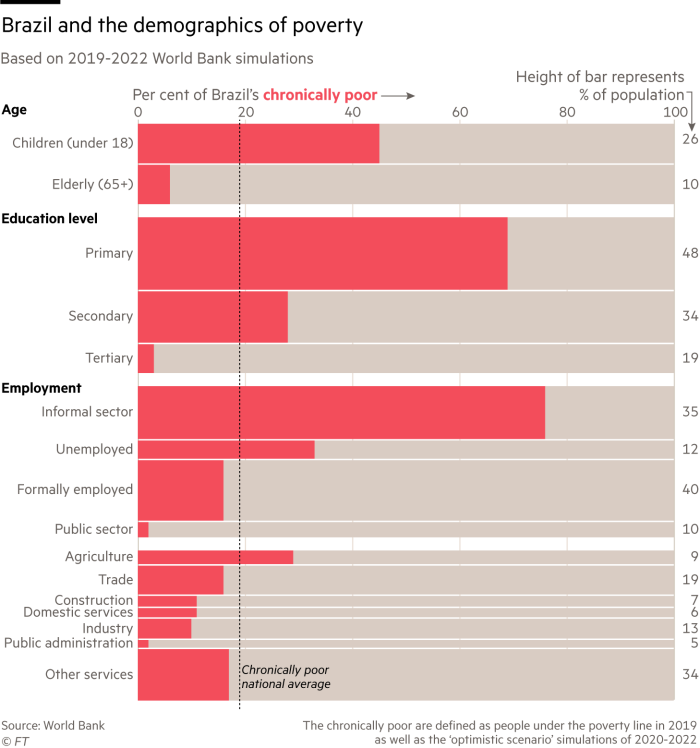

Since then, the economy has barely budged. Gross domestic product expanded just 0.15 per cent, on average, annually in the decade up to the end of 2021. Living standards have fallen in a country where the middle class had been expanding. And despite being one of the world’s foremost agricultural producers, food insecurity has risen.

“Brazil’s growth underperformance since the end of the previous commodity supercycles in 2014 has surprised even those who were pessimistic,” says Marcos Casarin, chief economist for Latin America at Oxford Economics. “Per capita income is still 10 per cent below its 2013 peak and will take at least another four years to return to that level.”

Political coverage in the build up to next week’s presidential election has been dominated by the controversies around the two leading candidates — whether incumbent Jair Bolsonaro will respect the result if he loses and the potential return to power of former leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva who spent time in jail on corruption charges.

But as Brazilians prepare to vote on October 2, it is the widespread decline in quality of life that is at the forefront of their minds.

“If you walk through downtown São Paulo or other cities, you will see there are a lot of people going hungry,” says Maria Isabel da Costa, who runs a restaurant in the city. “People are having a hard time maintaining themselves.”

Bolsonaro and Lula have both promised a path to prosperity but espouse starkly different visions for reviving Latin America’s largest economy.

Lula, a former trade unionist who governed Brazil between 2003 and 2010 at the height of the commodities boom, is leading in the polls by about 10 percentage points.

He wants to put the state back at the centre of economic policymaking and use government spending, notably on infrastructure, to spur growth. Yet much of his rhetoric has focused on past achievements rather than fresh policy proposals.

Under Bolsonaro, voters can expect a continuation of the free market, pro-business agenda of Paulo Guedes, his finance minister, who has focused on cutting bureaucracy, promoting privatisation and simplifying labour regulations.

Although largely overlooked by wider society, many of the administration’s microeconomic reforms have been lauded by the country’s business community.

Neither candidate, however, has focused on the difficult structural changes deemed necessary to improve productivity and generate long-term growth. These include an overhaul of Brazil’s notoriously complex tax system and the significant investments needed in infrastructure and education.

This partly comes down to political priorities. But it also reflects how, under Brazil’s system of proportional representation, no candidate’s party ever wins a majority in Congress, the federal legislative body.

Whoever is elected president will be forced to deal with the Centrão — literally, the “big centre” — a loose political bloc encompassing almost half of the lower house’s lawmakers, who lend support in exchange for funds to plough into their home constituencies.

This pork barrel politics undermines growth by diverting precious government resources away from where they are most needed, critics say.

“The Centrão will continue to be the most important political group in Congress and whoever is the next president will have to negotiate with them,” says Bruno Carazza, a professor at the Dom Cabral Foundation.

Evandro Buccini, economist at Rio Bravo Investimentos, says growth will prove elusive without big reforms. “We have low investment rates, low saving rates, the deterioration of the demographic profile and, the most important one, a lack of productivity growth. In terms of productivity, Brazil has stagnated for the past 20 to 30 years,” he says.

“If you want to talk about [improving] productivity, you need to talk about education and trade, neither of which are detailed in Lula or Bolsonaro’s plans.”

Deeper need for change

The Bolsonaro administration did not hide its glee when the latest growth figures were released this month. “Brazil is flying,” cheered Guedes, after data showed GDP expanded 1.2 per cent in the second quarter from the previous quarter.

It was an unexpectedly buoyant result that prompted several investment banks to revise forecasts for this year upwards to more than 2.5 per cent. Services drove the recovery, complementing commodities exports, which have become a bedrock of the economy.

“This year is much stronger than we imagined,” says Guido Oliveira, chief financial officer of shopping mall operator Iguatemi. “The population had pent up income.”

It came on top of a reduction in unemployment, which has fallen below the double digits to the lowest point since 2015, and also falling inflation. Yet for all the government’s crowing in the run-up to the election, the longer-term horizon remains cloudy.

Economists expect GDP growth to slow next year to less than 1 per cent as a confluence of high interest rates, an unfavourable global scenario and potential political uncertainty take a toll.

The deeper issue though is that Brazil has struggled to find an effective and sustainable model for broad economic growth.

In the years leading to the 2014 crash, Dilma Rousseff’s leftwing administration used spending to keep up momentum. This, combined with a simultaneous collapse in the price of commodities, eventually resulted in a fiscal crisis, which snowballed into the recession.

“Brazil used to grow due to the influence of the public sector; the state and the state-owned companies were geared towards supporting economic growth,” says David Beker, chief Brazil economist at Bank of America in São Paulo. “Brazil needs to search for new engines of growth because the state cannot grow more.”

Although agribusiness has surged in recent years and now accounts for more than 25 per cent of GDP, the gains have been offset by a long decline in industry.

Industrial output shrank by about one-fifth in the 10 years to late 2021, according to the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics.

It is a phenomenon described as “premature” deindustrialisation, since the loss of manufacturing occurred earlier than would be expected given the country’s stage of development.

Many blame what is known as the custo brasil: the combination of bureaucracy, a complex tax system and poor logistics infrastructure that elevates the cost of doing business in the country.

For others, it is also a legacy of Brazil’s relatively closed economy and residue of protectionist policies, which they argue has resulted in a lack of competitiveness and dynamism.

“Most of the industries in Brazil are far behind other countries. We need to reindustrialise,” says Luiz Tonisi, chief executive of semiconductor group Qualcomm in Brazil, who suggests homing in on sectors with the most potential.

“We had a lot of chicken flights over the last years,” he adds, referring to short, limited periods of growth. “Why? Because we did not make the reforms, we did not do the infrastructure, we did not invest where we should have invested. If we want a decade of growth, we need to do all this.”

‘Taxes are a mess’

Guedes — educated at the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman, the father of the monetarist school of economics — came to office with a pro-business agenda.

His successes include a landmark overhaul of pensions in 2019, helping secure the independence of the central bank, as well as a host of microeconomic reforms aimed at increasing the ease of doing business.

“The attraction of investments into infrastructure has also been positive, with multiple concessions and the privatisation of [power utility] Eletrobras,” says Lucas de Aragão, a partner at Arko Advice, a political consultancy. “Media often overlooks these themes, since it is a government that generates a lot of controversy.”

Most analysts expect a continuation of these economic policies if Bolsonaro wins a second term and Guedes has signalled he would stay on as finance minister.

To date, however, his agenda of major structural reforms has mostly floundered. Paramount among them is a shake-up of the country’s byzantine tax system.

“Taxes are really a mess and this drags us down in terms of consumption and investment,” says Tonisi.

A midsized Brazilian company takes more than 1,500 hours to prepare and pay taxes, according to World Bank data — the highest in the world. By contrast, a US counterpart takes 175 hours and a UK business about 110 hours.

Dealing with this was a central objective for Guedes but he has little to show for it. An attempt to pass a limited tax reform, which among other measures would have introduced a tax on dividends, is stuck in the Senate.

Tax reform is a particularly knotty endeavour because of the plethora of competing interests, notably Brazil’s 27 states and thousands of municipalities, as well as influential corporate lobbies.

Critics are sceptical that Guedes has the nous to guide such projects through Congress and win over the Centrão, which increasingly calls the shots in Brazilian politics.

“Neither Lula nor Bolsonaro’s parties are close to reaching half plus one of the Congress [to pass legislation], let alone the two-thirds majority needed to approve constitutional amendments,” says de Aragão.

Securing the Centrão’s support, he adds, means the “government often has to water down, or downright forget, proposals considered extreme or ideological”.

Neglected infrastructure

Another widely acknowledged factor holding Brazil back is poor educational standards, leading to a skills shortage that weakens productivity.

“There is a chronic deficiency in the quality of education. Brazil spends around 13 per cent of GDP on pensions and approximately 6 per cent of GDP on education. The solution involves directing these resources more efficiently,” says Buccini.

Adjusting for inflation, government spending on education fell from R104bn ($20bn) in 2016 to R80bn last year, a 23 per cent drop. Defence spending remained stable in the same period.

“Certainly one of Brazil’s biggest problems is its poor basic education and the main cause of this is the disregard of the elected authorities,” says Ana Maria Diniz, founder of the Peninsula Institute, an education-focused non-profit.

Infrastructure is similarly plagued by a lack of investment. Poor quality roads and the absence of rail links dramatically increase logistics costs and reduce margins. In terms of sanitation, almost 100mn Brazilians lack wastewater services for the removal of sewage.

Redirecting resources to these areas, however, is not straightforward. More than 90 per cent of the government budget is pre-assigned to mandatory expenses, mostly public sector salaries and pensions. Overhauling this system would require an administrative reform of the state, one likely to be bitterly contested by a multitude of vested interests, including the Centrão.

For many investors with exposure to Brazil, the immediate post-election worry is the country’s approach to rectitude in the public accounts. Both Bolsonaro and Lula have demonstrated a propensity to spend when politically expedient.

“Neither of the candidates’ proposals highlight a commitment to promoting a stable macroeconomic environment, rooted in low inflation, sustainable fiscal policy and predictability,” says Mariam Dayoub, chief economist at Grimper Capital. “They focus on proposals that increase spending [and] lack ideas on how to boost productivity.”

The concerns centre on the future of the public sector spending ceiling implemented in 2016, known as the teto. By limiting growth in the budget to the rate of inflation, it is viewed as a key fiscal anchor.

Ahead of the election, Bolsonaro has circumvented the cap in order to increase social welfare payments, while Lula has been open about his desire to abandon it altogether.

This is the “biggest near-term risk,” says Jared Lou, a portfolio manager at William Blair Investment Management. “That’s the key thing to watch out for in this election.”

The lure of Lula 2.0

Lula has made no secret of his plans to shift the centre of gravity in the economy. “The state needs to take the lead,” the former president said this month. “The state has to use all its powers of influence so that we can develop this country and convince businessmen and foreigners to invest in Brazil.”

He has also spoken about a return to a greater role for the national development bank; suggested the government should take a firmer hand in the running of Petrobras, the state-controlled oil producer; and also enact legislation to better protect workers.

The leftwinger also talks about reducing inflation — now at 9 per cent — and forging a more progressive tax system, although he has offered scant details on how he would do either.

Lula insists his time in power is evidence of his fiscal responsibility. Critics, however, blame him for the start of a more interventionist approach embraced by his successor, Rousseff, who was impeached in 2016.

Elena Landau, an adviser to Simone Tebet, the fourth-placed candidate in the presidential election, argues Lula set the stage for the nation’s economic woes. “From an economic point of view, he left us in a very bad position. By the time he left, he had exacerbated countercyclical policies, fiscal spending and intervention in state-owned companies,” she says.

Wagner Parente, chief executive of consultancy BMJ, adds: “Although Lula is unlikely to adopt the same economic policies as Rousseff, some specific goals — such as overturning the government spending cap — bring uncertainty to the private sector.”

So far financial markets have been sanguine about a potential new Lula presidency, mostly owing to the fact that he is a known quantity who is perceived as moderate on economic policy.

He also enjoys a better reputation among many western investors, who fretted over Bolsonaro’s at times authoritarian rhetoric and blatant disregard for the environment.

The business elite believe Brazil could reap enormous dividends from “green” investments and combating climate change, if the next administration in Brasília shows more interest in protecting the Amazon.

Despite a surge in the destruction of the rainforest, Brazil still maintains 60 per cent of its native forests — a much higher level than western nations — and almost 80 per cent of its electricity comes from renewable sources.

“Brazil has great potential to lead the decarbonisation agenda on multiple fronts, notably energy transition but also nature-based solutions — carbon capture via reforestation, for example. We also have the opportunity to lead on frontier segments, such as green hydrogen,” says Gabriel Brasil, an analyst at Control Risks.

But he cautions overall growth depends on “structural reforms and increased institutional stability”, adding that both Lula and Bolsonaro are likely to face challenges.

Beker is more bullish, saying the country is primed to grow if it maintains fiscal discipline and continues reforming: “We have big potential for ESG investments. We are far away from conflict and it is peaceful country. The question is, can we capitalise on that?”

Additional reporting by Carolina Ingizza

[ad_2]

Source link