[ad_1]

The US central bank will lift its benchmark policy rate above 4 per cent and hold it there beyond 2023 in its bid to stamp out high inflation, according to the majority of leading academic economists polled by the Financial Times.

The latest survey, conducted in partnership with the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, suggests the Federal Reserve is a long way from ending its campaign to tighten monetary policy. It has already raised interest rates this year at the most aggressive pace since 1981.

Hovering near zero as recently as March, the federal funds rate now sits between 2.25 per cent and 2.50 per cent. The Federal Open Market Committee gathers again on Tuesday for a two-day policy meeting, at which officials are expected to implement a third consecutive 0.75 percentage point rate rise. That move will hoist the rate to a new target range of 3 per cent to 3.25 per cent.

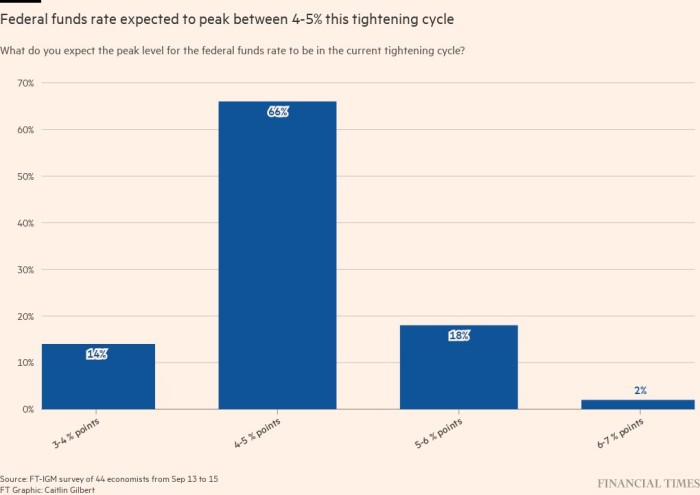

Nearly 70 per cent of the 44 economists surveyed between September 13 and 15 believe the fed funds rate of this tightening cycle will peak between 4 per cent and 5 per cent, with 20 per cent of the view that it will need to pass that level.

“The FOMC has still not come to terms with how high they need to raise rates,” said Eric Swanson, a professor at the University of California, Irvine, who foresees the fed funds rate eventually topping out between 5 and 6 per cent. “If the Fed wants to slow the economy now, they need to raise the funds rate above [core] inflation.”

While the Fed typically targets a 2 per cent rate for the “core” personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index — which strips out volatile items like food and energy — it closely monitors the consumer price index as well. Inflation unexpectedly accelerated in August, with the core measure up 0.6 per cent for the month, or 6.3 per cent from the previous year.

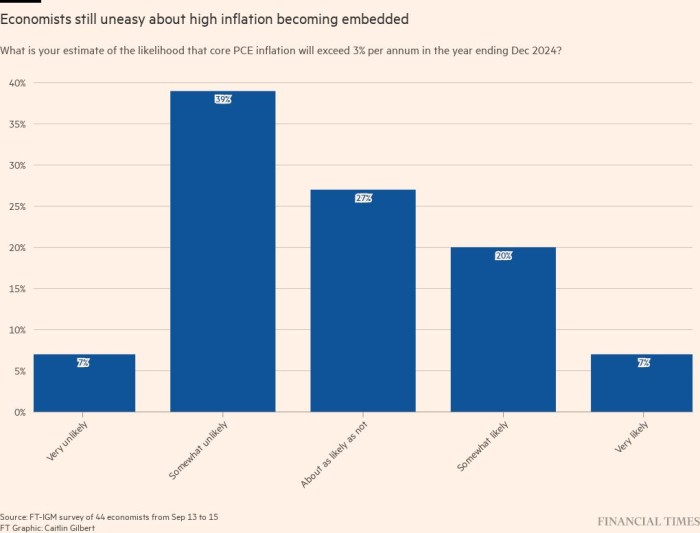

Most of the respondents project core PCE will drop from its most recent July level of 4.6 per cent to 3.5 per cent by the end of 2023. But nearly a third expect it to still exceed 3 per cent 12 months later. Another 27 per cent said “it was about as likely as not” to remain above that threshold at that time — indicating great unease about high inflation becoming more deeply embedded in the economy.

“I fear that we have gotten to a point where the Fed faces the risk of its credibility seriously eroding, and so it needs to start being very cognisant of that,” said Jón Steinsson at the University of California, Berkeley.

“We’ve all been hoping that inflation would start to come down, and we’ve all been disappointed over and over and over again.” More than a third of the surveyed economists caution the Fed will fail to adequately control inflation if it does not raise interest rates above 4 per cent by the end of this year.

Beyond lifting rates to a level that constrains economic activity, the bulk of the respondents reckon the Fed will keep them there for a sustained period.

Easing price pressures, financial market instability and a deteriorating labour market are the most likely reasons the Fed would pause its tightening campaign, but no cut to the fed funds rate is anticipated until 2024 at the earliest, according to 68 per cent of those polled. Of that, a quarter do not anticipate the Fed lowering its benchmark policy rate until the second half of 2024 or later.

Few believe, however, the Fed will augment its efforts by shrinking its balance sheet of nearly $9tn via outright sales of its agency mortgage-backed securities holdings.

Such aggressive action to cool down the economy and root out inflation would have costs, a point Jay Powell, the chair, has made in recent appearances.

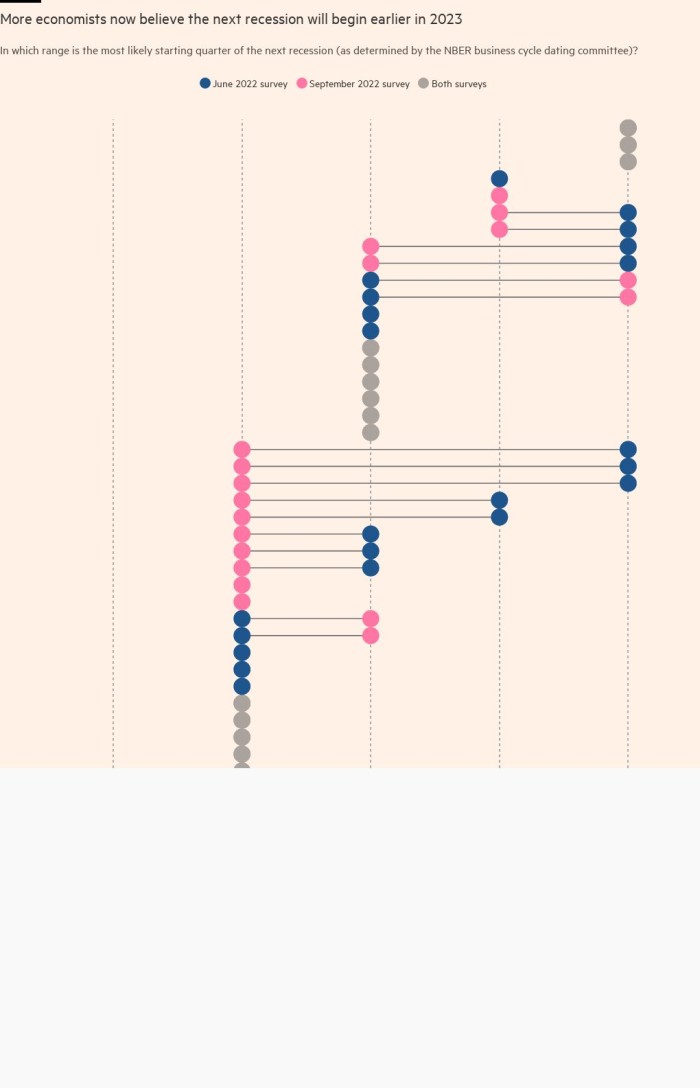

Nearly 70 per cent of the respondents expect the National Bureau of Economic Research — the official arbiter of when US recessions begin and end — to declare one in 2023, with the bulk holding the view it will occur in the first or second quarter. That compares to the roughly 50 per cent who see Europe tipping into a recession by the fourth quarter of this year or earlier.

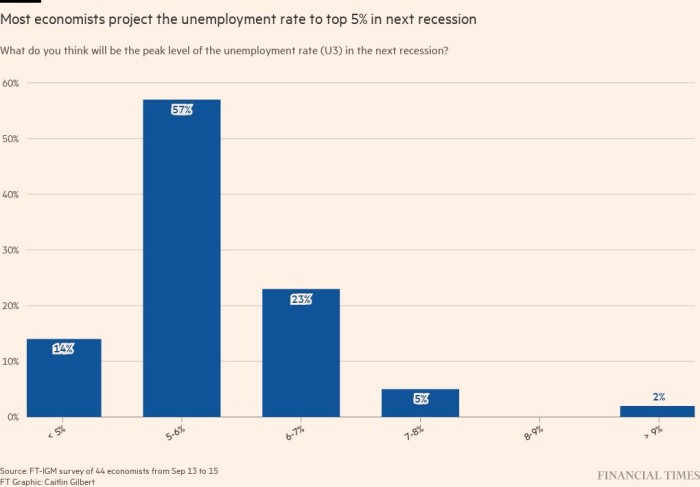

A US recession is likely to stretch across two or three quarters, most of the economists reckon, with more than 20 per cent expecting it to last four quarters or more. At its peak, the unemployment rate could settle between 5 per cent and 6 per cent, according to 57 per cent of the respondents, well in excess of its current 3.7 per cent level. A third see it eclipsing 6 per cent.

“This is going to fall on the workers who can least afford it when we have rises in unemployment due to these rate increases at some point,” warned Julie Smith at Lafayette College. “Even if it’s small amounts — a percentage point or two of increase in unemployment — that’s real pain on real households that are not prepared to weather these types of shocks.”

An easing of supply-related constraints related to the war in Ukraine and Covid-19 lockdowns in China could help minimise just how much the Fed needs to damp demand, meaning a less severe economic contraction in the end,” said Şebnem Kalemli-Özcan at the University of Maryland. But she warned the outlook is highly uncertain.

“Clearly this is one shock after another, so I’m not confident this is going to happen right away,” said Kalemli-Özcan. “I cannot tell you a timeframe, but it is going in the right direction.”

[ad_2]

Source link