[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday

Welcome to my first appearance in the Trade Secrets newsletter since the end of July. In case you missed them, the two excellent editions in the interim by Financial Times colleagues are here (the great Edward White on grounds for optimism on fisheries subsidies) and here (the magnificent Andy Bounds on how US climate policy became trade policy and created a transatlantic row over cars).

No big surprise about the two (related) themes that have emerged over the summer and which we’ll be looking at from various angles in coming months. One is climate change, the impact of which is underlined by the current horrors in Pakistan on top of droughts around the world. The other is what the now fast-arriving energy shock means for globalisation. Since you ask, here’s my column from last week about how energy self-sufficiency and energy security are not the same thing.

As ever, I’m on alan.beattie@ft.com and my Twitter DMs are open at @alanbeattie for hints, tips, special requests, offers to pay my gas bills in London this winter, knitting patterns for thermal gloves and so on. Today’s Charted waters looks at how Russia’s energy squeeze complicates Europe’s battle with inflation.

Get in touch. Email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

The forces that governments struggle to control

Today’s newsletter will sketch out the broad themes of what I’m likely to be writing about over the next few months — though let’s be honest, the remarkable capacity of the world’s governments, weather systems and malign pathogens to push globalisation off course means it’s hard to make firm plans.

Time was, back before Covid-19 and beyond, the trade issue was more narrowly about trade policymakers doing trade policy, or at least so you would have thought from a lot of the (let’s be honest, not always lavish) media attention it got. And to be honest there often wasn’t that much policy about to make much of a difference in the real world. Multilateral trade deals that never happened, bilateral and regional agreements that often didn’t make a lot of difference when they did, a lot of legal argy-bargy over antidumping in mature industries such as steel and so on.

Well, there’s now rather a lot of substantive traditional trade policy about: Donald Trump’s tariffs against China, which President Joe Biden has just announced will largely stay in place indefinitely, the US’s local-content requirements in electric vehicles, the EU tooling up with a bunch of unilateral measures against allegedly subsidised, dumped or unethical imports, the battle for dominance of the Asia-Pacific with the CPTPP and so on — not to mention the blackly amusing sideshow of the UK’s hapless Conservative party finding out what the Brexit a bunch of them fervently voted for actually means.

But the real action in globalisation more broadly defined these days isn’t trade policy as such: even extraordinary interventions such as Trump’s trade war with China haven’t been as cataclysmic as you might have thought. More important are the direct effect of events in the real world, particularly the economic cycle, climate change and the energy shortages, and the collateral effects from governments setting policy in other areas.

The massive real-world shock in the near future is the coming economic crunch. Obviously this is likely to be bad for trade in the near term, at least in goods. Imports have traditionally dropped a lot further during a recession than growth overall. On the other hand, as we’ll explore in future newsletters, the world saw big inflationary-recessionary crunches in the 1970s and 1980s, and they didn’t stop the medium-term march of globalisation. Even the massive collapse in goods trade during the financial crisis in 2008, and then again in the first year of the Covid pandemic, haven’t sent the post-cold war surge of globalisation into reverse.

Climate change in its various manifestations also has the potential directly to affect trade and globalisation in the medium term. But it’s not at all clear in which direction it will go in terms of increasing or reducing cross-border commerce. As my esteemed colleague Helen Thomas points out, freight barges being unable to progress down the dried-up Rhine or Danube will concentrate minds on the threat from relying on shipping. Companies may wish to shorten supply chains accordingly. On the other hand, if unreliable harvests create shortages in populous food-importing countries they will require more imports rather than fewer.

Similarly, you might assume that higher energy prices and hence transport costs will reduce the returns to long-distance trade in goods with low profit margins, and lead to shorter supply chains and the reshoring of production. But then again, as European manufacturers have discovered, more expensive fuel can also provide incentives for the offshoring of energy-intensive goods such as bicycle parts to Asia where power costs are generally lower.

On the policy side, explicit trade-related actions such as the electric vehicle credits in Biden’s big climate change bill are important. But a vast spending programme designed to put the US at the forefront of the renewable technology is a much wider issue for the world economy in the long run than the specific trade-focused aspects. (Also, it’s much less likely to be a bad idea overall.)

Similarly, there are attempts to put trade policy at the service of geopolitics, including an expanded sanctions regime from the US and EU, and lots of talk about governments encouraging their companies to “friendshore”, that is construct supply chains with political allies. But in reality, the geopolitical developments that are really likely to affect companies’ decisions in the medium term are the much more fundamental ones. Overwhelmingly, the biggest thing the US can do to affect the configuration of supply chains in the Asia-Pacific is to protect Taiwan from even a credible threat of Chinese military incursion, not fiddle around signing minor regulatory co-operation deals with its allies there.

Globalisation is too important to be left to governments, and the future of trade is definitely too important to be left to trade policymakers. We’ve got a far more robust global trading system than the often feeble or wrong-headed response of governments deserves. Let’s see if we can keep it.

As well as this newsletter, I write a Trade Secrets column for FT.com every Wednesday. Click here to read the latest, and visit ft.com/trade-secrets to see all my columns and previous newsletters too.

Charted waters

The big economic news item this week will be the European Central Bank rate-setting committee’s decision on how far and how fast to tighten eurozone monetary policy. The expectation is for an aggressive move, raising the benchmark deposit rate to 0.75 per cent.

Trade — or rather the breakdown in trade via the Ukraine conflict — is at the centre of this issue. The primary cause of the inflation surge is the sharp rise in wholesale gas prices in Europe, fuelled by Russia throttling gas supplies.

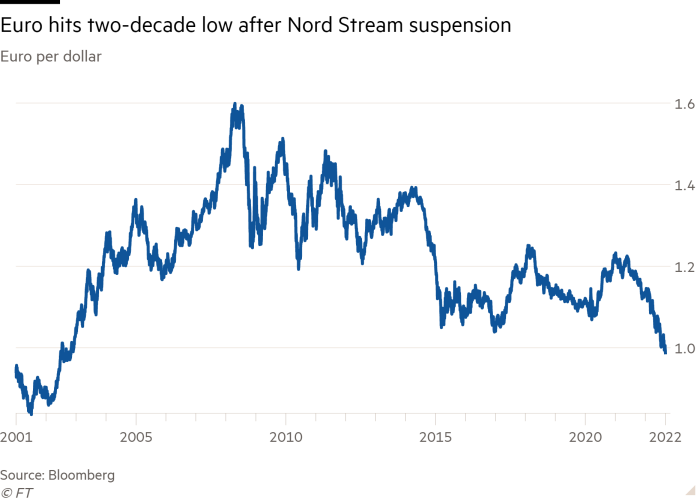

Russia’s decision to indefinitely suspended natural gas flows through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline spooked the markets, pushing down the euro to a 20-year low against the dollar, further fuelling inflation by pushing up the prices of imports to the EU, especially energy. This complex problem is not going to go away easily and the solutions are likely to be painful. (Jonathan Moules)

Trade links

The academic Richard Baldwin, the globalisation wonk’s globalisation wonk, has embarked on an epic multi-part assessment of the state of said phenomenon, which starts here (and to which I will return).

The former US Treasury international finance guru Mark Sobel, in a lengthy post for FT Alphaville, says that the global architecture for resolving sovereign bankruptcies is messy (as I noted here in July), but there’s going to be no sweeping reform, so better deal with it as it is. He’s very likely right.

The EU is set to make it much harder for Russian travellers to get visas, following demands from central and eastern member states. There’s already political tension with Turkey after a sharp rise in rejections of Turkish applications for visas for the free-movement Schengen zone inside the EU.

The US ambassador to Japan (and former Barack Obama chief of staff) Rahm Emanuel muses about the next era of globalisation.

My former student politics contemporary Liz Truss will today almost certainly be announced as the new prime minister of the UK, and as the FT’s excellent Britain after Brexit newsletter points out here, she is surrounded by a bunch of ideological deregulators and sovereigntists whose ideas appear somewhat at odds with business reality.

Trade Secrets is edited by Jonathan Moules

[ad_2]

Source link