[ad_1]

Oh no! A trolley is heading towards five people. You can pull the lever to divert it to another track, killing one person instead. What do you do?

-

If you don’t believe the trolley is on your track then pull the lever shortly after it kills five people, you could be an equity analyst.

-

If you do nothing because one trolley is a proven lead indicator for multiple trollies that are expected to kill all six people, you could be a markets strategist.

We talked a little last week about how the balance of analysts’ forecast upgrades to downgrades remains in positive territory for US, UK and European markets, even as strategists warn about a multi-year global recession. What results is a gap between top-down and bottom-up earnings predictions that’s so wide, it doesn’t even fit on Berenberg’s graph template any more:

As we wrote back then:

The job of an equity analyst is to smell the air and tap the ground around their assigned industry so they can get a sense of what’s coming. Mostly, they do this by speaking to the executives of companies under their coverage.

When things are going well, this is a very good system. The executives guide the analysts towards a sensible sounding number then beat it each quarter by 5-10 per cent. Everyone’s happy. The methodology falls apart during downturns because the executives are confident they’re taking the right actions to protect profitability, meaning their companies will outperform peers. Each analyst therefore gets only a Panglossian view of reality. Forecasts stay too high for too long.

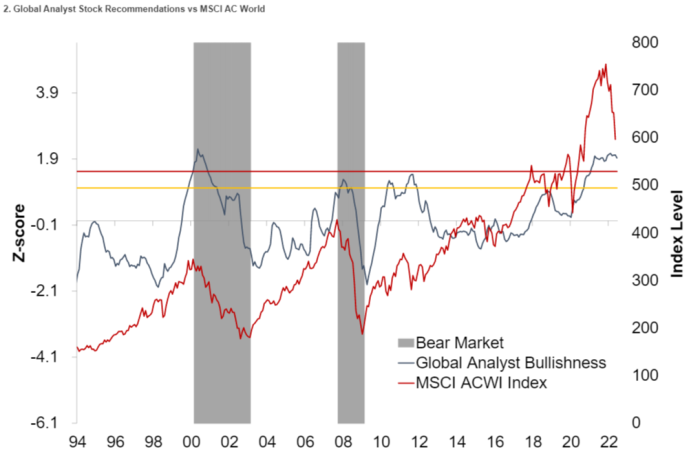

Supplementary evidence for the case against analysts comes from Citigroup strategist Robert Buckland, whose latest flags that sellside optimism “is back to peak bullishness levels reached in 2000 and 2007, after which global equities halved.”

The chosen measure here is recommendations, not forecasts.

Because analysts are always net positive with stock recommendations, Citi uses a z-score that measures bullishness relative to the long-term average. Its plot matches market performance fairly well — though how much investor activity is inspired by sellside calls and vice versa is a matter for debate.

Whichever way, stocks and analysts’ confidence in them seem to rise lockstep. At least for a while:

That’s until we hit irrational exuberance, which is easy to spot at the 2000 and 2007 peaks. Less easy to explain is the burst of over-optimism in the middle of the eurozone debt crisis, after which stocks went sideways; theories welcome in the comment box.

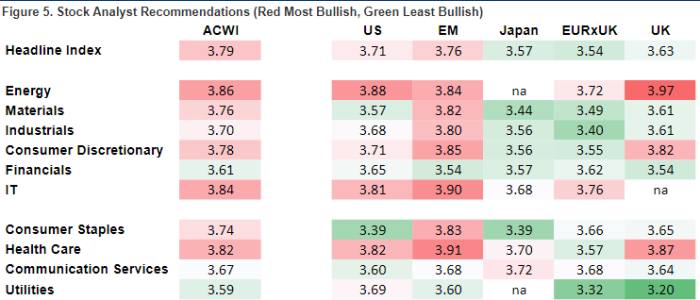

Anyway, Citi’s gauge is back at 2007 bullishness for all kinds of everything. “In no region or global sector are analysts more cautious than they were two years ago,” Buckland writes. “Any investor worried that analysts are currently too optimistic should probably be more concerned about the red boxes than green boxes.”

“The lagged relationship between recommendations and profit forecasts suggests a state of denial at the beginning of a bear market,” he says. “Analysts keep positive stock calls, despite starting to make cuts to their profit forecasts. They eventually cut their recommendations, but it takes time.”

An obvious response is to argue that sellside recommendations are always too compromised to be useful (which might be true), and strategists are always gloomy by nature (ditto). There’s also the complication that Mifid II changed incentives both for analysts and IB clients, meaning the period after 2018 might not be directly comparable with what came before.

Still. By putting the three-month swing of earnings revisions over the buy/sell ratio Citi arrives a conclusion that European and Japanese utilities are the least likely to disappoint, because their numbers are being upgraded reluctantly. In the opposite quadrant is . . . almost everything else:

[ad_2]

Source link