[ad_1]

This article is the latest part of the FT’s Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign

When Wayne Chapman received a text informing him of fraudulent activity on his current account last September, his first thought was to ring his bank.

But before he could do so, someone had called him. They told him they were from the fraud squad and had spotted unusual activity on his account.

“If they’d asked me about my account number I would have twigged sooner — they were just saying ‘there are people trying to access your money’,” says Chapman, a car mechanic. “But as soon as I said ‘Can I take your name and call you back,’ their tone changed entirely.”

The scammers took £2,000, although TSB, Chapman’s bank, refunded the full amount.

The UK faces an “epidemic of fraud”, according to financial services trade body UK Finance and more than 140,000 calls have been made to a scam helpline since it was set up in September by Stop Scams UK, an industry-led collaboration.

During the pandemic, criminals adapted their methods to exploit victims’ fears over coronavirus, and are now finding new avenues of attack in the cost of living crisis. Yet campaigners and the financial services industry are concerned that flagship policies proposed to beat fraud are being delayed by political uncertainty at the heart of government.

“Consumers desperately need protections fit for the digital age,” says Rocio Concha, director of policy and advocacy at consumer group Which?, adding that the online safety bill had the potential to stop millions of pounds of scams every year. “The government must commit to passing this important legislation. Any backtracking would be an unforgivable betrayal of scam victims.”

The state of scams

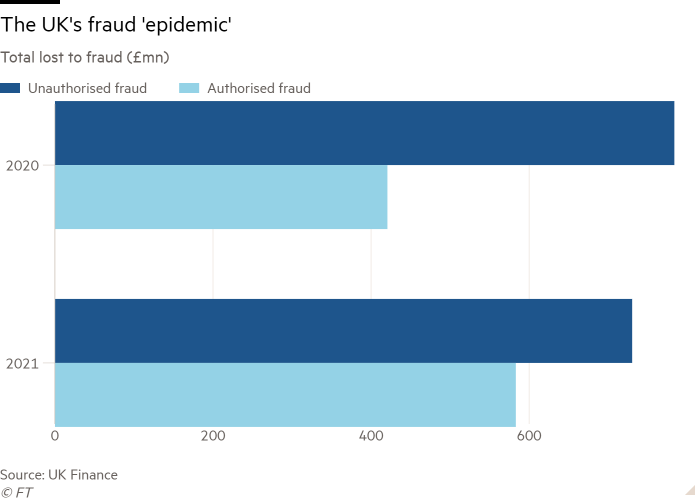

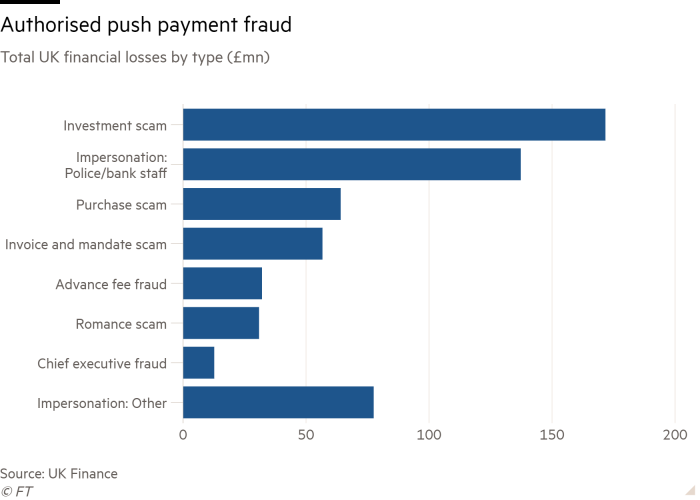

Fraud rose from £1.2bn in 2020 to £1.3bn last year, according to a recent UK Finance report on scams, yet this modest increase was not evenly distributed across different types of scam. So-called “authorised push payment” (APP) fraud, in which victims are conned into transferring money into scammers’ accounts, leapt by 40 per cent to more than £580mn by value of losses.

“Since Covid-19 hit, we’ve seen a higher rate of APP fraud because of a tightening on card spending, and we anticipate further growth,” says Paul Davis, director of fraud at TSB.

Impersonation scams — the type of fraud experienced by Chapman in which scammers pretend to be police, bank staff or from the tax authority — have also seen a significant increase. Losses rose by 15 per cent in 2021 to £96.6mn.

“They were very clever. They weren’t asking for things like the account number but they were describing what they were doing,” says Chapman. “I thought — they’ve got the details, they must be the bank.”

Eventually, he smelled a rat. “They said that they’d patch you through to a business manager, but after a little while I started thinking that their voices were familiar, like they were sitting around a table. At that point, when I asked they didn’t want to give me their name.”

Equally alarming are investment scams, which have increased by almost 60 per cent to £171.7mn in 2021 and now make up the biggest share of APP fraud. These can be highly sophisticated, moving across platforms and gaining users’ trust, with many focused on cryptocurrency investments. One victim in the US was approached on an investing-related Facebook page in 2021.

“We started chatting back and forth over the next few weeks, they started telling me about really cool stuff in the cryptocurrency market,” says the man, who asked not to be named, adding that he had not previously been interested in digital assets.

Eventually he was invited to a group on Telegram, the messaging app, which maintained the illusion of financial advice, although in retrospect he says the traffic was likely to have come from bots or “sockpuppets”, accounts appearing to be those of separate individuals, but which are controlled by one scammer.

“You just see people every day posting encouragement to other customers and pictures of their supposed gains — it’s all staged,” he says. “Everyone has glowing reviews until you look a bit deeper, and these are the same people talking over and over again, using the same kind of speech patterns.”

The group claimed to offer products including a 90-day managed investment, as well as a “special ETF” which it claimed was offered to only the best customers. He was encouraged to invest in cryptocurrencies, which the group said was necessary for security purposes.

The problems started when he went to withdraw the funds and was told he had to pay a 20 per cent commission — which, due to “regulatory laws” could not simply be taken from funds in the account.

“That’s the last hurrah — the last bit of money they try and extract. Once you send them the commission, they kick you out of the channel, block you and you have no more access to them,” he says.

In total he lost around $20,000 to the scammers, who went as far as to run a fake Instagram account of a real financial influencer and sent the victim a doctored photo of his driving licence.

He lost an additional $5,000 to another investment scam on Telegram, which offered additional gains in return for inviting other people to join.

“The day [for cashing out] hits and the website is done. You message them on Telegram and they say everyone is trying to withdraw at the same time [so] give us three business days,” he says. “That buys them time to cover their tracks.”

The use of cryptocurrencies by fraudsters to spirit away money is unsurprising, says Mark Steward, executive director of enforcement and market oversight at the Financial Conduct Authority.

“Cryptocurrency scams are some of the most reported at the moment,” he says. “We regulate these companies’ anti-money laundering systems, but we don’t regulate the products.”

The issue is not restricted to the UK. According to data from the US Federal Trade Commission, almost 40 per cent of the $1.1bn lost to fraud on social media in the 15 months to March 2022 was related to digital assets.

Not all such scams are sophisticated. Squid Coin, a token named after, but entirely unrelated to the hit Netflix show Squid Game, cost investors more than $3mn despite red flags, including obvious spelling mistakes.

Davis at TSB says the lender had been blocking payments to cryptocurrency exchanges for more than a year because of the high incidence of scams. “We couldn’t make it past the 20 per cent fraud rate — it was off the scale,” he says.

One exchange which was used by scammers to steal £50,000 from a consumer asked TSB to remove its block. When Davis asked it to look into the fraud claim, he says he heard nothing back. “I just don’t think a lot of them care about customer protection.”

CryptoUK, the UK trade association for digital assets companies, did not respond to a request for comment.

Cost of living

Banks and others have also warned of an increase in crimes which seem calculated to play on consumers’ insecurities as the price of living continues to rise, with annual inflation at a 40-year high of 9.4 per cent.

“Scammers continue to ruthlessly exploit the cost of living crisis and the uncertainty caused by the war in Ukraine,” says Simon Miller, director of policy and communications at Stop Scams, an anti-fraud group whose members include lenders, telecoms companies and some Big Tech firms.

One such area is a rise in advance fee fraud — in which customers looking for a loan are told they have to pay a fee to access credit, but never see the money they need.

“We’re very much concerned about a sudden increase in advance fee scams — up to 90 per cent — that we’ve seen, although it’s still relatively small volumes,” says Liz Ziegler, retail banking director of fraud and financial crime at Lloyds Banking Group.

The FCA on Thursday said it had relaunched a campaign warning the public about loan fee fraud, after inquiries to its call centre over this type of scam jumped by 36 per cent in June 2022, compared with the same month last year.

Scams exploiting the financial stress of soaring energy bills have also been on the rise. Research by online protection company McAfee found scams naming one of the “big six” energy firms were up 10 per cent in the first three months of the year compared with the same period last year, with a 27 per cent year-on-year rise in January alone.

Criminals typically send potential victims an email pretending to be from an energy supplier, inviting them to claim a refund due to a “miscalculation” on their bill. In doing so, customers are invited to submit personal information such as their bank details, which can then be used by the scammer to steal money.

David Lindberg, chief executive of retail banking at NatWest, says another concerning trend was the rising number of money mule scams in which criminals encourage users to let them transfer ill-gotten money via their accounts to cover their financial tracks.

“It’s not becoming a mastermind or setting up an operation,” he says. “It’s someone getting in contact, saying ‘just put this money in your account’. It’ll be a £1,000 and they’ll leave £100. It doesn’t feel like a crime.”

However, it is usually the mules who are caught, he says. Banks are then legally obliged to close their account and report them to the authorities.

Katy Worobec, managing director for economic crime at UK Finance, says many of those caught up in money mule schemes do not realise the implications or dangers, and are drawn in by advertisements on social media offering easy money.

Trying to identify those recruiting mules required close collaboration with the social media platforms on which their fraudulent messages are hosted, she adds.

“We want to try and work with the online platforms which are allowing those things to be hosted,” she says. “Can they use their algorithms to find those scammers before they recruit people?”

Delayed action

The role of social media companies in scams has long been a point of contention across the financial services sector, with some platforms accused of not doing enough to combat scammers.

“We’ve seen a classic trickle down effect,” says Steward. “Once Google was no longer allowing these scam ads to appear on its paid-for advertising pages, you saw immigration to other sites, including Microsoft and various search engines, and an increase on sites run by [Facebook owner] Meta.”

Digital bank Starling pulled its advertising from Meta platforms at the end of 2021 over fraud. Last month, Starling chief executive Anne Boden says she still felt Meta had not done enough to protect consumers.

“We have a huge problem here,” she says. “And it’s not just older people or the vulnerable who are being tricked and scammed into giving away their life savings.”

Meta said promoting financial scams was against its policies and it was dedicating “significant resources” to helping combat it.

“We recently started rolling out a new process that requires all financial services advertisers to be authorised by the FCA so they can run ads targeting users in the UK,” it said.

Microsoft declined to comment.

There were hopes that this could change with the online safety bill, a wide-ranging piece of legislation that would force platforms to deal with harmful content.

While the bill has generated considerable concern over its potentially chilling impact on free speech and opportunities for encryption, it would make big tech companies responsible for combating free and paid-for scam advertising on their platform.

The bill was due to have been debated in July, but its reading has been paused until at least early September, when MPs return from their summer recess.

“Industry needs certainty to be able to invest to help keep people safe. The delay to the bill has only created uncertainty,” says Miller at Stop Scams UK. “That is bad for business and bad for consumers. The only people that will benefit from the uncertainty are the scammers.”

Worobec at UK Finance says the industry needed to remain vigilant to ensure the bill succeeded. “We need to keep a weather eye on it to see that it doesn’t get weakened in any shape or form,” she says, adding that she supported more collaboration between companies in different sectors rather than waiting for legislation further down the line.

Banks and others are also calling for clearer guidance on data policy, to ensure they can access information without falling foul of competition or privacy rules.

“We need clearer legislation that recognises the need for the banking and other sectors to share data more readily in the pursuit of economic crime,” says Lindberg at NatWest.

The government says it remained committed to cracking down on the scammers who target the British public, adding that “tackling fraud requires a unified and co-ordinated response from government, law enforcement and the private sector, including online platforms, to better protect the public and businesses”.

Fraud is fundamentally not a domestic issue, says Steward.

“The way that fraudsters operate is that they’ll continue to innovate,” he says. “We need a global consensus surrounding this, the same way that major markets have securities regulations for financial markets.”

How to avoid becoming a scam victim

-

Look for red flags in emails, texts or social media messages, such as spelling and grammatical errors as well as a messy layout and impersonal greetings. You should also check whether the note has come from a familiar number or company, though scammers often attempt to spoof these credentials.

-

Impersonation scams are increasingly common. Be wary of any calls from supposed figures of authority, especially bank staff or police, which require you to provide financial details, especially if they attempt to rush you.

-

Look out for deals that are too good to be true, such as investment portfolios which will give rapid, high-end returns.

-

Scammers can masquerade as influencers, professionals or even fellow investors to lure victims, and can create elaborate online structures resembling professional operations. The Financial Conduct Authority’s website has a list of genuine companies whose details you can check.

-

Do not move money for people you don’t know. This is called money muling, and can lead to prosecution even if you are unaware you are moving illegal funds.

-

When looking for loans, remember that genuine companies will not ask for an upfront payment before releasing the funds.

-

If you remain in doubt after an unexpected or potentially fraudulent call, contact the Stop Scams UK service on 159, which can get you through to your bank.

[ad_2]

Source link

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.