[ad_1]

A year ago, Britain’s wealth managers were banking on a post-pandemic economic recovery, with their clients already profiting from a surge in financial markets rising in expectation of the good times to come.

Things have not turned out that way. Inflation has soared to the highest levels since the 1970s, energy prices are at unprecedented levels and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has stoked fears of global instability. Meanwhile, in China, the government’s rigid zero-Covid policies have reminded investors that the pandemic remains a threat — to growth and supply chains as well as to human life.

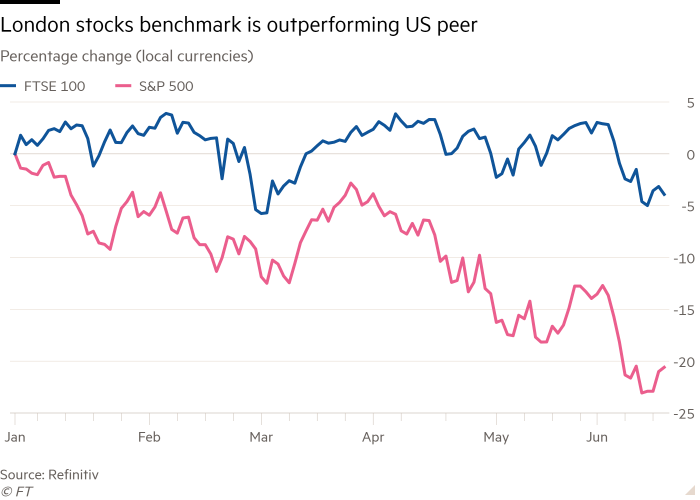

Global equity and bond markets have plunged in response, led by a 30 per cent drop this year in the same US Nasdaq index of tech companies which had led the upward charge only a few months earlier. The broader S&P index is down 20 per cent, signalling that the nervousness is spreading far and wide.

It’s a relief for British investors that the FTSE 100 is down only about 5 per cent. But that’s scant consolation when inflation rates in the UK are heading above 10 per cent and, as elsewhere, bond yields are soaring, driving up borrowing costs — with the yield on 10-year gilts jumping from around 1 per cent to 2.55 per cent this year.

The market turmoil is bringing collateral damage, especially in cryptocurrencies, which have been shunned by most UK wealth managers but not necessarily by their customers.

Even seasoned observers have been surprised by the speed with which the tide has turned. As Keith Wade, chief economist at Schroders, the investment group, says: “In 30 years of forecasting, I can say this is a particularly uncertain time . . . The economists have been caught out.”

For wealth managers, the top priority is to help nervous clients weather the storm. “People want to talk to advisers more,” says Chris Woodhouse, chief executive of Evelyn Partners, the advisory group formerly known as Tilney Smith & Williamson. “The history of retail investors is that they buy at the top and sell at the bottom. The onus is on advisers to keep clients comfortable when markets are fragile . . . The message is ‘don’t panic’.”

At the same time, wealthier Britons are still coming to terms with the impact of the pandemic. While their money protects them from the economic disruption of the outbreak and the inflationary surge, it has left them asking questions about their financial future. “Covid made clients re-evaluate their planning, their needs and their legacy,” says Eva Lindholm, head of wealth management for the UK and Jersey at Swiss bank UBS, the world’s largest wealth manager.

As advisers told FT Money for this wealth management special edition, all this comes at a time of multiple challenges for the industry. These range from a longstanding cost squeeze, as customers press for lower fees, to the demands of the environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment agenda and the advance of digital technology.

A confusing range of choices

For investors, the choice of advisers has never been greater. From bespoke face-to-face services to online-only support via a combination of face-to-face and online, there are services to suit different preferences and pockets.

But making a selection remains tough — despite recent improvements in transparency, comparing fees, investment performance and quality is a struggle. Many private investors rely, as they always did, on subjective recommendations from family and friends or lawyers and accountants they happen to know. Objective data remains fragmentary: there are no league tables for wealth managers.

Ian Mattioli, co-founder and chief executive of Leicester-based investment manager Mattioli Woods, says clients seek out wealth advisers for many reasons. “They talk about a lack of good quality advice at do-it-yourself investment platforms. They started investing online and now want to speak to somebody. They have collected a hodgepodge of investments and now want help. They have got a new job, sold a business or come into an inheritance. They don’t like their current [wealth manager’s] charges.”

To help readers make their way through this thicket, FT Money looks at UK wealth managers, focusing on firms offering discretionary management. Together with Savanta, our research partner, we are publishing a list of top wealth managers with detailed corporate information.

Private Client Wealth Management 2022

These companies focus on savers with £250,000 to £5mn to invest, though most are happy to take on much larger portfolios. Above £5mn, big private banks, including Swiss and US groups, become increasingly competitive with their global offerings. Under £250,000 it becomes increasingly difficult to give frequent face-to-face advice profitably. But tech is helping to reduce costs, allowing firms to combine personal advice with automated and semi-automated services, and so compete with tech-based robo advisers.

By pushing many client meetings on to computer video channels, the pandemic has encouraged customers to go digital. In a survey by Boring Money, a consumer-oriented research group, the proportion of people feeling comfortable with video call meetings has jumped from 25 per cent in 2019 to 60 per cent this year.

UK wealth to keep growing despite economic uncertainty

With the UK’s wealth stocks growing over the past decade, boosted by rising financial asset and property prices, there is no shortage of potential business for advisers. Even with the recent market turmoil, companies report strong growth in client assets, notably from company owners selling up in what the industry likes to call “liquidity events”.

In a report, BCG, the management consultancy, forecasts that UK financial assets will grow 3 per cent annually to 2026, a prediction that takes account of the current market sell-off. That’s only slightly slower than the 4 per cent recorded in the two decades to 2021, a bumper time for investors. It implies that wealthier Britons will continue to accumulate money, even as the cost-of-living squeeze hits the worse off.

Most savers lack financial advice. Of a total of 37.9mn savers, only 3.4mn, with £992bn, currently receive wealth advice. Boring Money estimates there are a further 13.2mn people with financial assets and cash of £840bn who either have “low confidence” about investing or do not invest.

While the financial decision makers in British households have traditionally been men, women are increasingly taking control in older households, often as widows after their partners die. Women have long outlived men, but the baby-boomer generation now passing into old age and beyond is the wealthiest in history, so more widow-led families have money to manage.

They are being joined by growing numbers of women entrepreneurs and City professionals with self-made fortunes. Mary-Anne Daly, chief executive of Cazenove Capital, the wealth advisory arm of Schroders, says: “It’s exciting to see the growth of wealthy women.”

Retail investment service companies have been falling slowly in number in recent years, in the face of growing technology and regulatory costs, and dipped in 2020 to 5,017 firms, according to the Financial Conduct Authority.

Larger companies are growing faster than smaller rivals through expansion and takeovers. Among the posts at financial adviser firms, which account for about three-quarters of retail investment services businesses, companies with more than 50 advisers raised their share of all adviser posts in 2020 to 49 per cent, from 47 per cent in 2019, says the FCA.

In general, consolidation driven by the costs of regulation and technology tends to favour big well-capitalised groups, such as the Swiss specialist wealth banks, US investment banks and universal banks such as HSBC, Barclays, Deutsche and Lloyds. Helen Watson, chief executive of UK wealth management at Rothschild, says: “One of the reasons we see industry consolidation is that rising costs make it more cost effective to be bigger.”

The biggest recent deal is Royal Bank of Canada’s planned £1.6bn acquisition of Brewin Dolphin, one of London’s largest and oldest independent wealth firms founded in 1762. It follows close on the £279mn sale of Charles Stanley, established in 1792, to Raymond James Financial, a US investment bank.

Banks catering to the very wealthy have invested in lower market segments, as with Goldman Sachs of the US, adding a robo-advisory service to Marcus, its digital consumer bank, and rival American bank JPMorgan Chase buying Nutmeg, the robo-adviser. UBS’s Lindholm says: “It’s a very vibrant industry. And It definitely got more vibrant during the pandemic. We see a lot of banks coming into the private client asset management space offering technology capabilities, but clients still value human interaction.”

But big banks do not have the field to themselves, as private equity firms are also driving deals. The recent rebranding of Tilney Smith & Williamson as Evelyn Partners followed Tilney’s £625mn acquisition by Smith & Williamson, backed by private equity shareholders Permira and Warburg Pincus, which created one of the UK’s largest wealth advisory companies.

There is also plenty of activity among smaller firms: companies with five advisers or fewer, accounting for around 90 per cent of all advisory companies, face particular cost challenges. As owners retire they are often selling out to rivals, if only to ensure their clients are looked after.

At Mattioli Woods, Mattioli says: “Consolidation can’t go on forever. But there is sufficient space in the market for some more consolidation.” Established in 1991, the company last year capped a string of smaller deals with the acquisition of Ludlow Wealth Management Group for up to £43.5mn and private equity specialist Maven Capital Partners for up to £100mn.

Meanwhile, new companies are launching into the market, often with a digital offering. Wealthtec was identified as one of the UK’s growth segments in last year’s government report into fintech.

Anna Zakrzewski, BCG’s global head of wealth management, says that capital is flowing into digitally-oriented companies, putting higher valuations on such businesses compared to less digitally-oriented ventures. “There is a tech acceleration. Three of four years ago [acquiring companies] paid for client access. Now they pay for digital as well.”

Fees and costs matter

In principle, all this competition should be good for clients. The range of options is greater than three decades ago, when big firms were national and small firms local. Now, small firms with tech capacities can cover the country.

For many clients, costs are a key consideration. After regulatory changes forced companies to be more transparent about charges, wealth managers trimmed fees, using digital technology to reduce their costs. This is not likely to change any time soon. One chief wealth executive says: “I don’t see client fees being raised. So margins will be squeezed further, not just for us but for the wider industry.”

Customers increasingly question the traditional method of levying fees annually as a percentage of the assets under management (AUM), typically 1.6 per cent (less on very large portfolios of £5mn and more). These clients prefer to pay one-off fees on the basis of specific services such as the preparation of a financial plan or a pension restructuring. Boring Money found in a survey that among people looking at charges as a reason for choosing an adviser, 86 per cent sought information on service-based fees.

Big banks boast of their wide investment offerings and skill sets. But they are often criticised for offering smaller clients a worse deal than their wealthier customers.

McInroy & Wood, an investment manager with 70 staff, based in East Lothian, has clients coming on board complaining they were badly served by banks, says Tim Wood, the chief executive and main shareholder. He emphasises that they offer “personal client service, with every client having their own investment manager and dedicated administrator”.

So even if economies of scale favour bigger companies, and very small firms are struggling with rising costs, many medium-sized independents are still confident of their place in the market.

Whatever their size, firms have their work cut out, guiding clients in today’s economic conditions. In Savanta’s survey, wealth managers summarise their customers’ view of the stock market. At nine of 22 firms clients say it is “somewhat overvalued” and at one “very overvalued”. Only five give positive answers, with seven not giving a view.

The wealth managers too are fairly cautious — 14 of 21 say they don’t expect the FTSE 100 index, currently at around 7,200, to cross 10,000 in the next five years. Only one sees it doing so by the end of next year.

While strategies differ, many wealth managers argue that with cash deposits still returning very low returns, the arguments for staying invested in securities remain strong, as the right portfolio can mitigate the impact of inflation. William Dinning, chief investment officer at Waverton Investment Management, says it’s time to review portfolios. “It’s not that the bad times have arrived, but the good times have gone.”

The crypto conundrum

With cryptocurrencies tumbling this year, the wealth managers who spoke to the FT for this survey were almost unanimous in declaring this had little or nothing to do with these markets — even if customers invest on their own initiative. As Wood at McInroy & Wood says: “If clients want to dabble by themselves on the side in a small way that decision is theirs.”

Wealth managers taking this approach may feel vindicated for now. But some in the industry think that the broader world of fintech has a future — as an investment and a potential source of partners. BCG’s Zakrzewski says: “Our message is not that wealth managers should do crypto. We are saying wealth managers should think about what it means for them.”

She argues that younger clients want their advisers to have access to crypto. While regulations often prevent managers advising on digital currencies, there are, she says, ways of providing crypto-linked services — notably through partnerships with crypto companies.

The ESG investment agenda has come under pressure this year. The surge in fossil fuel prices has reminded investors of the profits still to be made from extractive industries. Meanwhile, public criticism of the implementation of ESG investment rules has intensified. It has even resulted in a police probe — in Germany, at DWS, the wealth manager controlled by Deutsche Bank, over allegations of greenwashing — which DWS denies.

But wealth managers insist that investors remain committed to ESG. And with good reason since the Ukraine crisis is expected to accelerate green energy investments as a means of cutting dependence on imported oil and gas, especially in Europe.

Woodhouse at Evelyn Partners says: “Clearly, regulatory standards for ESG on companies are rising and asset managers will have to continue to show they are good stewards of capital.”

Can your adviser deliver?

With so much to do, implementation is perhaps the single most important differentiator between wealth companies. Almost all can talk fluently about ESG, as they can about digital technology, markets, pensions or tax. But not all can deliver what they promise.

That means clients are wise to shop around and see what is on offer, particularly if they think the 2020s will be a tougher decade for investment than the 2010s. Top-quality advice and service will be at a premium.

As BCG says in its report: “Wealth clients are in no mood to wait for next-generation offers and next-level service. They want them now . . . if not from their current wealth advisers, then from others.”

[ad_2]

Source link