[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Ethan and I are still reeling from one of the most consequential Federal Reserve meetings we can remember. Today we try to widen the lens and look at the economic context. Are we missing anything? Let us know: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Is the Fed kicking an economy that’s already down?

Yesterday markets sent an unambiguous signal. Stocks fell hard across the board, with the exception of a handful of consumer staples and healthcare companies. Bond prices rose (and yields fell). Translation: “There is going to be a recession! The Fed just told us that it is going to cause one to get inflation under control!”

But take a step back. What is the state of the US economy? Is the Fed going to tighten financial conditions in an economy that is already weakening — threatening not just a recession, but a deep one? What is the range of possible outcomes?

We know a few important, if somewhat stale, facts. The labour market is very strong; there are twice as many job openings as job seekers. As of March or April, personal consumption, industrial production and business investment were growing in real, inflation-adjusted terms.

At the same time, however, there are lots of anecdotal, company– or industry-specific examples of slowing growth, giving the impression that cracks are forming in the economic facade.

We also know that sentiment is terrible. Surveys of consumers and businesses are showing ugly results, because rapid price increases scare everyone to death, as they well should. But thus far, this has not been having a noticeable effect on real activity. So let’s exclude survey data and look exclusively at activity.

What is actually happening?

First, the housing market is clearly slowing. With mortgage rates near 6 per cent and climbing, demand is getting smooshed. The Mortgage Bankers Association index of purchase mortgage applications is down a third from its peak in January. Sales of existing homes are declining, but not as fast as those of new homes, which have fallen off a cliff along with housing starts, as this chart from Pantheon Macroeconomics shows:

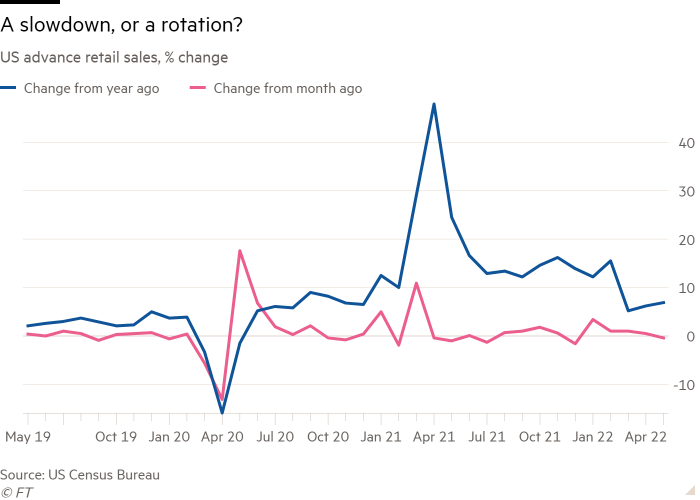

Outside of housing, activity measures are sending much more ambiguous messages. The May retail sales report, which showed a 0.3 per cent fall from April, caused a certain amount of hand-wringing about the impact of inflation on consumption. One competitor’s story was headlined “US retail sales declined in May as inflation stings consumers”. Excluding autos, though, sales were up 0.5 per cent in nominal month-over-month terms. And it is not clear if softening retail sales do not reflect the long-awaited rotation back towards services after a period of forced spending on goods. Consider this chart:

The dip in month-to-month sales growth (pink line) looks less ominous in the context of the extraordinary bolus of growth — more easily visible in the year-over-year data (blue line) — that we just passed through.

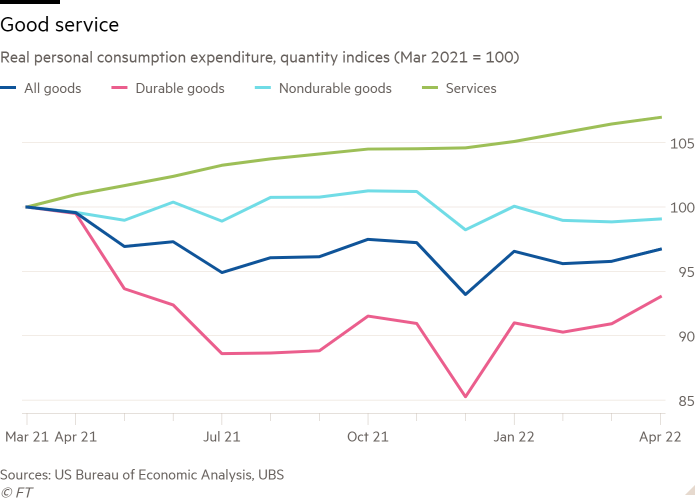

Spending on durable goods surged during the coronavirus pandemic, and remains far below its March 2021 peak. Meanwhile, services spending has been rising gradually, and will probably jump even more this summer as everyone goes on holiday, believes Evan Brown of UBS Asset Management. The rotation is clear in the real PCE quantity index, which measures how many goods and services consumers bought in a month:

In other words, we may not be looking at falling demand, but a shift on where demand is going.

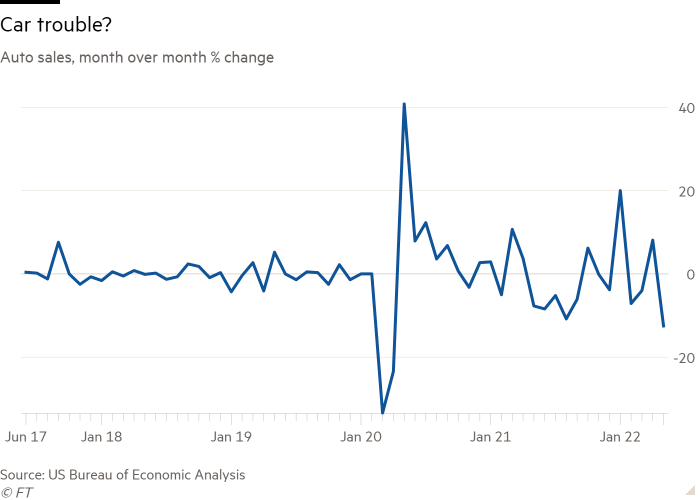

So what about cars? Vehicle sales fell 12 per cent in May, but look how volatile the data are. The industry’s supply chain problems make underlying demand hard to decipher:

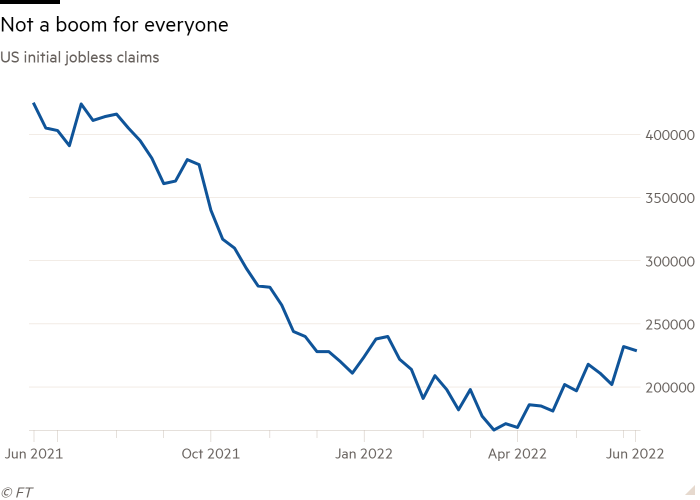

Finally, jobless claims are sending faint signs that the labour market, while still red-hot, is cooling slightly:

To judge by activity measures, the US economy is slowing, but the slowdown to date is slight and is concentrated in a few significant areas, primarily housing. The Fed’s sledgehammer — as we have described it — will land on a relatively strong economy, not one balanced on the edge of recession.

The much hoped-for “soft landing”, in which inflation abates without significantly higher unemployment, is all but ruled out. We think the likelihood of a recession, defined crudely as a few quarters of negative growth, is very high, given the Fed’s posture. The central bank is all but determined to make a recession happen, but its depth remains an open question.

At the same time, the range of possible economic outcomes remains wide. This is partly because, as we have seen above, demand appears so resilient. Supply will matter too. The Fed cannot count on supply relief, but it may come, and if it does, the possibility of a shallow downturn is much higher. The market is badly spooked, but the economic story is not yet written. (Armstrong & Wu)

One good read

A tiny climate silver lining: the polar bears of southeastern Greenland have learned to hunt on glacier ice, as sea ice melts. Maybe they will be OK?

[ad_2]

Source link