[ad_1]

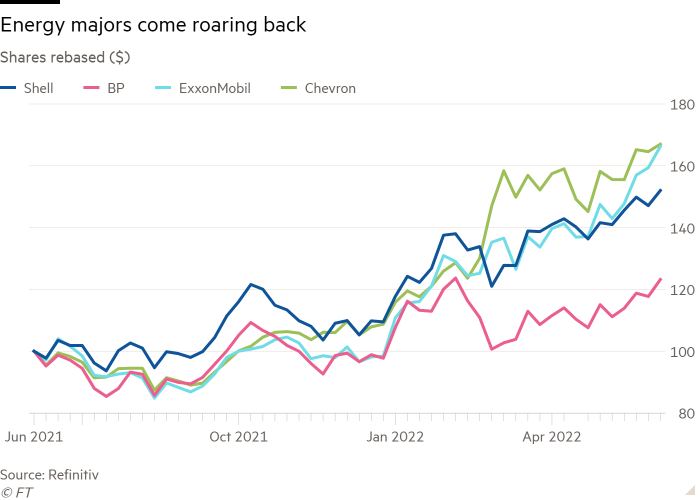

Oil and gas is back in fashion — at least on the stock market. Soaring fossil fuel prices, pushed higher by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have helped the shares of the world’s biggest energy majors outperform every other sector since the start of the year.

After a bruising coronavirus pandemic, when oil demand collapsed and BP’s shares fell to a 27-year low, the so-called supermajors have come roaring back in 2022.

Shares in UK-listed Shell, Europe’s biggest oil company, are up 47 per cent since January, while BP’s have climbed 37 per cent. By contrast, the FTSE 100 is up less than 2 per cent, while the S&P 500 is down 14 per cent.

France’s TotalEnergies and Italy’s Eni have risen 26 per cent and 16 per cent respectively. But the biggest winners are the US supermajors. Texas-based ExxonMobil is up 71 per cent and has promised to buy back $30bn worth of stock, while Chevron is up 54 per cent.

It was not supposed to be this way.

Before Covid-19 slammed into the global economy, oil and gas companies were already finding it harder to attract investors as pressure to cut emissions increased and climate activists called on shareholders to divest. After oil prices plunged as low as $20 a barrel in April 2020, BP and Shell cut their dividends, Exxon was dropped from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, and it appeared that the old supermajors would be banished to the margins of the investing landscape forever.

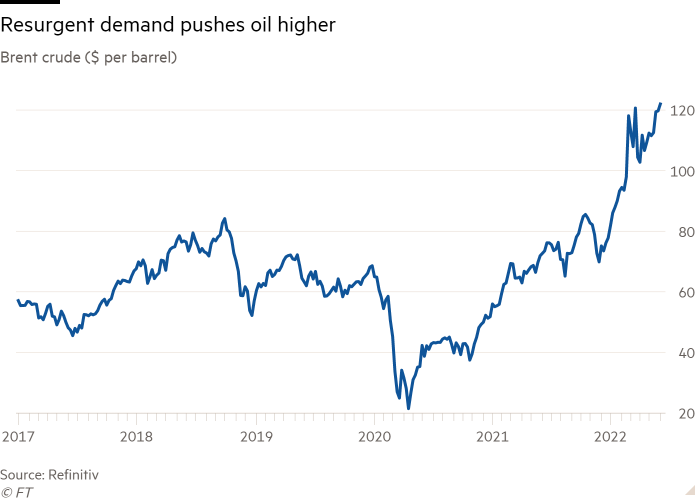

But since January two things have happened: Brent crude, the global benchmark, has climbed almost 60 per cent; and a growing international boycott of Russia, the world’s biggest energy exporter, has pushed energy security back to the top of the policy agenda.

Even BlackRock — in the past a big backer of more aggressive corporate climate targets — has eased back on its demands that energy majors cut down their polluting oil and gas businesses. The disruption of global commodity flows due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had increased the need, in the short and medium term, for companies that invest in “both traditional and renewable sources of energy,” the world’s biggest asset manager said in May.

Both BP and Shell have pledged to cut future oil production and it would be near impossible for them to reverse course by dramatically increasing output, say analysts. Indeed, despite bumper profits in 2021 and the first quarter of 2022 the supermajors have generally left spending plans for this year unchanged.

Instead, the biggest companies are expected to continue returning more cash to shareholders through share buybacks and dividend increases. Shell, for example, will buy back $8.5bn of its own shares in the first half of 2022.

“Shell is buying 25 per cent of the daily traded volume [of its shares] every day,” says Oswald Clint, an analyst at Bernstein. “That’s huge”.

With share buybacks expected to bolster prices further and many traders forecasting oil and gas prices to remain high, it begs the question of whether retail investors should also review their attitude to the sector?

Inflation haven

To some extent investors already have. Lucas Mantle at data provider VandaTrack says retail investment flows into US oil companies Exxon, Chevron, ConocoPhillips and Marathon Oil had all increased in the past two months, with investors “likely chasing momentum” achieved in the first three months of the year.

On Freetrade, a UK-based retail trading platform, BP was the ninth most popular stock in May, up from 19th in April. Over the past three months, Shell was the 46th most popular stock, up from 108th in 2021, while Exxon rose from 316th to 119th.

How to invest: the big UK producers

The easiest way for retail investors to gain exposure to the rally in oil and gas prices is through the shares of the biggest oil and gas producers.

Laura Suter, head of personal finance at investment broker AJ Bell, says Shell is currently the 13th most held asset and fifth most held share on its retail platform Youinvest. BP is the 15th most held investment and the sixth most held share.

With many analysts forecasting oil and gas prices to remain high, the two UK-listed energy majors could continue to generate bumper profits for the rest of the year, with both management teams promising to return much of the cash to shareholders via dividends and buybacks.

However, retail investors should not bank on continued share price appreciation, warns Lee Wild, head of equity strategy at retail investment platform Interactive Investor. The value of oil and gas stocks has already rallied, in Shell’s case by as much as 170 per cent in the past 20 months.

“If you’re buying at multiyear highs then there’s a lot of good news already factored into share prices,” Wild says. “That’s not to say that oil stocks won’t continue to do well [but] whether they have got further to rise is unclear and depends on many factors.”

Much of the relative performance of the energy majors this year can be linked to the surging oil price and the impact of inflationary fears on the rest of the stock market.

As early as November, analysts at JPMorgan were predicting that Brent crude would hit $125 a barrel in 2022 due to resurgent demand and the inability of oil producers to boost output quickly enough after years of under-investment.

Oil then touched a 14-year high of $139 a barrel in March after Russia invaded Ukraine, as traders weighed whether possible sanctions would ultimately deprive the 100mn barrel a day global oil market of the 7-8mn b/d of crude and refined products that Russia exports. The largest ever release from the US government’s emergency oil stocks have since helped calm prices. But at $123 a barrel it is still at its highest level since 2012.

At the same time, inflation and rising interest rates have weighed on the performance of those consumer-facing technology stocks, such as Apple and Alphabet, which have powered stock market gains in recent years, particularly in the US. Shares in Apple are down almost 20 per cent this year on investor fears that the rising cost of living will curb consumer spending. In a stark sign of shifting investor sentiment, the iPhone maker was overtaken in May as the world’s most valuable company by oil producer Saudi Aramco.

How to invest: the big European producers

While the share price performance of all of the European supermajors will remain closely linked to the oil price, some have more exposure to particular parts of the oil and gas sector.

Shell, for example, which reported its highest ever quarterly earnings in the first three months of year, is the world’s biggest trader of liquefied natural gas, the price of which has boomed in the past six months.

Norway’s Equinor has a large oil business but is also the second-largest supplier of piped gas to Europe after Russia’s Gazprom. It is set to benefit further as the EU attempts to reduce its dependence on Russian imports.

Record oil and gas earnings have also drawn the attention of regulators, with the UK, Italy and Spain all introducing some form of windfall tax on energy company profits. But such measures, including chancellor Rishi Sunak’s sweeping “energy profits levy” on North Sea operators, have had little or no impact on the share prices of the biggest producers.

“Investors have been looking for a different home for their money, and that’s why the FTSE 100 has done so well because it’s stacked with those old economy stocks, among them the oil companies,” says Lee Wild, head of equity strategy at retail investment platform Interactive Investor.

Investors, old and young

Ownership of the oil majors has traditionally been skewed towards older shareholders because these companies provide the regular dividend income that is particularly attractive to pension schemes.

Gemma Boothroyd, an analyst at Freetrade, says BP was consistently in the top 20 most popular stocks on its platform but added that, unusually, it had recently become more popular with younger buyers.

She attributes that shift to improved performance. “Reliable profits and consistent dividends make for an attractive offering during periods of high inflation and a cost of living crunch, irrespective of an investor’s age,” she says.

But BP, like most of its European peers, has sought to overhaul its image and business in the past two years and hopes more investors will come to see it as part of the solution to the climate crisis rather than the problem.

Bernard Looney, chief executive, has a regularly updated Instagram account, filled with smiling photos of the Irishman on his travels around BP’s global business.

In February he told the Financial Times he was committed to turning BP into a “one-stop shop” for clean, reliable, affordable power. “You cannot go against the grain of society and expect to be a long-term successful company,” he said.

Last month he told shareholders at the annual general meeting that by 2025, 40 per cent of BP’s capital would be spent on non-hydrocarbon parts of the business, specifically bioenergy, electric vehicle charging, retail, renewable energy and hydrogen.

Shell also insists it is changing. By the end of 2021 the company had cut emissions from its own operations by 18 per cent compared with 2016 and was committed to a 50 per cent reduction by 2030, chief executive Ben van Beurden told shareholders in May.

The ethics problem

Still, many people remain deeply sceptical of Big Oil’s promises. Shell’s annual general meeting — its first in London since switching headquarters to the UK — was delayed for almost three hours by activist shareholders protesting the group’s continued development of fossil fuels. Shell has said its oil production will fall by 1-2 per cent a year until 2030 but that it will continue to explore for new fields until 2025.

“When you scratch below the surface and look at their capital spending it doesn’t align with the rhetoric,” says Richard Brooks, climate finance director at advocacy group Stand.earth. “If they were transforming in a truthful way . . . then they would be stopping expansion projects today and there would be a lot more capital investment in renewables.”

Brooks argues that investors have a “moral responsibility” to move money out of fossil companies and support those businesses focused solely on cutting emissions. Stand.earth says that 1,508 institutions with assets totalling more than $40tn, including the endowment funds of Harvard, Oxford and Cambridge universities, have committed to divest fossil fuel stocks.

How to invest: smaller producers

In the past, smaller exploration and production companies have also been popular with UK retail investors.

Jadestone Energy, a producer focused on the Asia-Pacific region, is up about 30 per cent this year.

But social and political opposition towards oil exploration and production in many regions means the outlook for smaller companies is even more uncertain than for the more diversified supermajors.

But Wild at Institutional Investor points out that the bigger energy groups offer an opportunity for retail investors to get exposure to rising commodity prices while also investing in companies that are developing green technologies.

BP has pledged to build or acquire 50GW of renewable power by 2030, equivalent to the total current renewable generation capacity in the UK. Shell is investing heavily in wind power and hydrogen, while France’s Total in May made its biggest US renewable purchase yet with a $2.4bn acquisition of the wind and solar farm developer Clearway Energy Group.

“Investing in oil does add diversification to portfolios currently and you can comfort yourself in Shell and BP that both do have climate and sustainable strategies,” Wild says.

Nick Stansbury, head of climate solutions at Legal & General Investment Management, says investors seeking to align their portfolios with the goals of the 2015 Paris climate accord should seek the companies with the strategies that will best help the world hit net zero emissions by 2050, not just those with the lowest emissions today.

“Every company has to change the way they use energy. Every company has to think about how they abate their emissions and how they position to take advantage of the opportunities,” he says. “Those companies that swing behind that and invest everything in figuring out what their role to play is in delivering that solution, I am absolutely convinced, over the long term, will turn out to be far more profitable.”

How to invest: multi-asset products

Emma Wall, head of investment research and analysis at Hargreaves Lansdown, warns that stock- or commodity-picking can be a risky way to invest. “Commodities are highly volatile, and retail investors have missed much of the rally,” she says. “For most retail investors it is far better to stick to a multi-asset product where the professionals have the ability to invest in commodities on your behalf, blended with other assets to smooth returns.”

The iShare plc Core FTSE 100 ETF offers investors exposure to the 100 largest companies in the UK, including a hefty weighting to energy, materials and industrials stocks, including Shell, BP, Rio Tinto and Glencore. More sector-specific investment options include BlackRock’s Energy and Resources Income Trust, which is up 48 per cent since the start of the year.

For those retail investors seeking direct exposure to underlying commodities, Wall proposes Invesco Markets’ Bloomberg Commodity ETF, which tracks the performance of 24 commodities including Brent crude oil, gold, silver, copper, cattle, soy beans and corn.

“Given the significant rally in commodity markets, it is not surprising to see an ETF tracking the Bloomberg index among the most bought by investors year to date,” she says.

So while the fossil fuel rally may deliver bumper returns for oil and gas investors this year, the long-term question for the supermajors is whether they can successfully navigate the energy transition so that the biggest oil producers today become the biggest suppliers of green energy in 2050.

The short-term attractions are obvious, says Kingsmill Bond at the energy think-tank RMI, but he sees the recent oil and gas rally as a blip. “The artificial stimulus of Putin’s war will eventually fade, and then fossil fuel producers face a very bleak environment.”

Former BP chief executive Lord John Browne has argued that the oil and gas giants would be better served by placing their low- or zero-carbon activity and the legacy fossil fuel businesses into two different companies.

For now, all the supermajors — with the potential exception of Italy’s Eni, which is planning to list its retail and renewable power business — are pursuing a fully integrated future. Those companies that succeed will benefit from a diversified business that will be less exposed to the price of a single commodity, says Bernstein’s Oswald.

Over the next 15 years Bernstein expects the world to shift from an energy system dominated by oil to a system fed by several “almost equally weighted” inputs, including oil, gas, hydropower, nuclear, solar, wind and hydropower.

To succeed, Oswald says, “you need to be a big strong integrated [energy company] with a strong balance sheet and with fingers in every pie.”

[ad_2]

Source link