[ad_1]

When it comes to dividend-paying whole life (WL), there are direct recognition and non-direct-recognition policy loans. Direct recognition loans allow the insurance company to set a different dividend rate for a policy with an outstanding loan. With a non-direct-recognition loan, the dividend is credited as if no loan exists and the loan is charged a separate loan interest rate.

There is a difference of opinion about which is “better,” and, as might not be surprising, each carrier touts the benefits of the way it leans. I’m not interested in wading into that debate today.

I was recently involved in an analysis in which the plan could involve a significant policy loan. This proposal was with a carrier employing direct recognition, meaning, the dividend could be different when loans are taken. The fixed 6% loan rate was being touted as a backstop to potentially higher commercial lending rates in the future. I agree that this could be an important feature and I’ve noted it myself in some scenarios.

In this situation the dividend rate is 6% and the loan rate is 6% so it was positioned as a “wash” and the client was told the policy couldn’t backslide, meaning the loan couldn’t grow faster than the cash value collateralizing it. Let’s look closer to see if that’s factual.

The following is the email I sent to my client regarding this topic:

I’ve put something together for your review to illustrate a point. It’s important that you understand how policy loans work.

Let’s look at a hypothetical policy on your life. It’s a $10 million WL death benefit with 10 years of premium. There are no term blend or riders.

At age 76 (26 years from now), I had the software borrow as much cash value as is allowed, $15,244,000. You can see the net cash value and death benefit continue to grow for a while after this.

To an extent, we can duplicate the math on a calculator, but not everything because there’s a “black box” aspect to it, more so than with some other types of life insurance. In any given year, the increase in the loan amount under “Total Outstanding Loan” is the same as the number in the “Annual Loan” column. When you do the math you’ll see that it’s exactly 6%, as we would expect. When you look at the “Annual Dividend End Year,” that number doesn’t equate to 6% anywhere. It’s not how dividends work. It’s not even what dividends are.

Five years later, at age 81, the loan interest and the dividend are close, but not identical. Based on what you’ve been told you might expect this, but the total cash value is more than $4 million greater than the loan so the effective percentage rate must be significantly different. The effective rate of the loan, precisely 6%, and the effective rate of gross cash value growth (different from “dividend”) in that year, is also pretty close. The dividend itself, relative to gross cash value, however, is only in the 4 1/2% range, or 150 basis points less. Something that also makes little apparent sense is that the dividend is different if a loan is taken than if a loan isn’t taken. How can that be if the dividend is 6% either way?

When we look at the dividend rate as a percentage of total cash value when there’s no loan, it’s almost a whole percentage point lower. The dividend is a quarter million dollars more at age 81 when the policy has a loan, but why is that if the stated policy dividend rate is 6% whether or not the policy has a loan? Either way, when we see the cash value growing by more than the actual credited dividend, and neither the dividend or the growth in cash value equal to the stated dividend rate, there’s clearly more to it than meets the eye.

You’ll see the increase in the total loan from age 90 to age 91 is $2,068,000 while the increase in total cash value is $2,198,000, so it looks like the cash value is staying ahead. The dividend is a few hundred thousand dollars less than the cash value increase, which seems odd since the dividend is supposedly what’s driving policy growth. How exactly does the cash value grow faster than the crediting rate behind it? (I’m interested in figuring this out to take advantage of the phenomenon for my own portfolio.) The cash value grows by $130,000 more than the loan, but the net cash value increases by only $5,600. More importantly, however, the death benefit decreases by $127,000.

Let’s look at age 95. Here, the loan increases by $2,767,000 from age 95 to 96, and the total cash value increases by $2,815,000. Though the cash value appears to grow more than the loan, the net cash value drops by $119,000. The total paid up additions grow by over $2.5 million but the death benefit is reduced by over $400,000. At this point the dividend is projected to be $305,000 less than the loan interest, so where’s the “wash”?

The point is, it’s complicated. There’s a black box aspect to it. The loan goes up, the net cash value goes down, the paid-up additions go up, the death benefit goes down… If direct recognition was a wash, it seems like somewhere we’d see the cash value growth or dividend be 6% and certainly we wouldn’t expect to see the death benefit decrease by $4,225,000 from age 85 to 100.

Direct recognition, when the crediting rate and the loan rate are identical, isn’t a wash. Don’t take anything at face value. It’s always been this way, and anyone who’s honest about it knows the policy will never be credited as much as it’s being debited over time when there’s a loan on it.

Be very clear that I’m not stating this is bad. I’m not suggesting a WL policy with a loan isn’t going to work. All I am saying is that it doesn’t work like very many people believe it works. And this is a very clean example considering that the 6% interest and 6% direct recognition dividend rate are the same as the current 6% declared dividend rate by the carrier.

Bottom line, there is a spread between the interest charged and the dividend credited. Often the confusion is corrected by explaining that the Dividend Interest Rate (DIR) does not equal the dividend.

Dividend = DIR – The Guaranteed Rate – Expected Mortality & Company Expenses

From this simple formula it easy to see that there’s no mathematical way that 6% DIR and 6% loan interest would ever be equal values. The DIR in itself is only part of the calculation and not the calculation.

The whole life disasters that end up on my desk are often due to misunderstandings and, too often, misrepresentations, about policy loans.

I’ll also address an additional misconception that often is a result of misrepresentation. I’ve met with many policy owners who’ve told me something like the following: “I’m taking the loan from myself and getting credited the same loan rate so it’s a free loan. Another version is “The loan rate is 6% and I’m getting 5% crediting so the loan is only costing me 1%.” This is so ludicrous it begs belief. But it’s also so ingrained in some minds that countering it results in disbelief… I mean, an actual refusal to believe me.

If you were earning 5% on an investment and were being charged 6% on a separate loan, would you ever posture that as a 1% loan? Of course not. The fact that both the cash value and the loan are from the same insurance carrier is irrelevant. This is a 6% loan, end of story. If you took out a 6% loan, invested the money and earned 10%, would you call it a negative 4% loan? Nope. You might say you’re getting 4% positive arbitrage, but you still know you have a 6% loan. Let’s not talk make believe just because it’s life insurance or because it sounds better. Unless the examples above involve loans that are factually 0% or 1%, respectively, call them the 6% loans they are.

I find it interesting that the one place where there isn’t black boxing is the policy loan balance. Take out your own financial calculator, run the numbers above and you’ll duplicate the results, down to the dollar over any number of years.

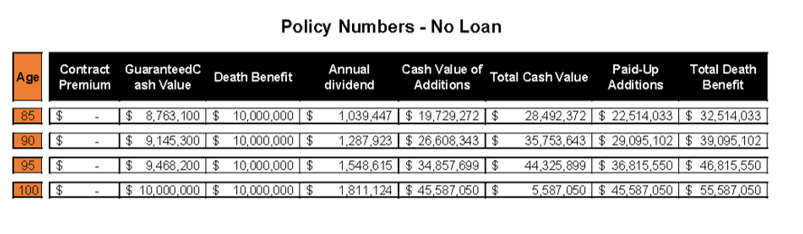

As always, it’s fun to “debate” from a point of truth, and yes, there are some truths. For the $10 million WL policy above, I didn’t have to run a second projection without a loan because it automatically includes it. At age 90, the ledger with the loan projects a net cash value of $4,191,000 and a net death benefit of $7,997,000. The ledger without the loan has a cash value of $35,753,000 and a death benefit of $39,095,000. Hmmmm… something’s changed. There is certainly an effect you didn’t understand. Of course, the policy owner has the money from the loan in hand, and/or the results of whatever was done with the money, but there’s clearly a tremendous effect on the policy. The most important aspect to note is that the death benefit growth slows down, peaks and then begins to backslide in the projection with the loan and it doesn’t in the projection without the loan. The longer you live, the worse it gets. This is specifically what you didn’t expect to happen based on how it was presented.

Yes, that’s a lot of numbers and I know it might not be totally clear. But if I can get someone to understand that life insurance, dividends and loans might be more complicated than previously thought, I’m making progress.

To illustrate just how crazy this can be, let me discuss a final point. When I put two otherwise identical ledgers side by side, one with the loan and one without, the dividend changes. The dividend rate is still 6% but the credited dividend number is different. Isn’t that against the rules of math? Look at age 85 in the tables above. The projected dividend without the loan is $1,039,000. With the loan the projected dividend is $1,391,000. How is that possible when the dividend is still 6%?

At age 76, the year the loan is taken, the dividend changes instantly; $160,000 to the positive when a loan is taken. Here’s why; the loan interest is precisely 6% every year. But a 6% dividend isn’t always a 6% dividend. There’s some fuzziness in there. There’s some leeway based on momentary market conditions, carrier experience, how the policy is being managed and factors you can’t know about. It doesn’t necessarily mean the insurance company is playing games (although it might be). In this case the dividend crediting is better with the loan but next year it might not be on the exact same policy even when the loan and dividend rates are the same as they are this year.

There are aspects that will not make sense and you won’t be able to figure out. Somewhere in the calculations there is likely something that is multiplied by .06 but the detailed expenses and potential additional crediting is probably never going to be known. There are some years where the cash value of the paid up additions portion of the policy grow at greater than 10% when the gross crediting is 6% before expenses. Some years it’s hundreds of basis points less even though the rate stays the same. I challenge you to figure it out. You’ll never be able to recreate the numbers, but you don’t really need to. If I make the statement that the agent telling your client how the policy works doesn’t actually know, I’ll be right far more often than not. Maybe they have a big picture sense of what is happening, but they don’t understand the details This is why the presentation is so often reduced to generalities and introduces emotion. So why does that matter? Because if you don’t understand the details, you can’t understand how it works and how to build and manage it efficiently and how things might go wrong and the consequences of it all.

This doesn’t make anything about the carrier projections wrong, but what you are told, or believe you understand, can’t be taken as gospel. Admit it, if 6% doesn’t even mean 6%, what can be taken at face value? We all (should) know that a 5% projection with one company can look better than 6% at another because there’s a lot more to it than just the crediting rate. If that can happen between different carriers, is it impossible to believe it can happen within the same carrier when policies are being managed differently by different policy owners? That’s what’s happening in this situation.

Besides, the projection your client looks at today assumes that every variable in the policy stays exactly the same forever as it is at this moment. That won’t and can’t happen. That positive dividend arbitrage based on the loan this year may very well not exist next year, and if it doesn’t, that $8.5 million spread in cash value at age 95 between the two projection would instantly vaporize. That’s meaningful. But that’s not much given the $40 million swing in death benefit at the same age. That swing is in the same ballpark as the total loan at the same point, isn’t it? Even if the crediting was the same as the loan interest, there are still tens of millions of a loan that is wiping out the death benefit. Too many people don’t even understand that!

Let’s revisit the 6% dividend/6% loan interest wash comment that was the original focus. There’s irony that in this policy with this carrier at this time, there’s factually some positive dividend arbitrage when a loan is taken our versus not taken out, but even then the policy backslides because the goosed dividend still isn’t enough to keep up with the loan interest. I’m sure the agent didn’t understand that because he may very well have touted the increased dividend as a reason to take a loan. Don’t laugh, I’ve seen it before. I’ve literally read emails where the agent tells the policy owners that the more loans they take out, the better the policy will do.

In closing, given all the variables in life insurance products, to make potentially lifelong decisions based on the ink that sticks to paper that comes out of the printer today, is a bit silly. Press the print button next week and the same ink, paper, printer, software and assumptions can result in something different. I’m serious. There’s not really much point in hanging one’s hat on what someone says when all that matters is what the contract states and the powers that be at home office decide every year.

What should you take from all of this Your clients aren’t going to figure it out. Trust me, they’re just not. They need help and it’s your job to convince them of that.

Bill Boersma is a CLU, AEP and LIC. More information can be found at www.OC-LIC.com, www.BillBoersmaOnLifeInsurance.info. Call 616-456-1000 or email at [email protected].

[ad_2]

Source link