[ad_1]

Jay Newman was a senior portfolio manager at Elliott Management, and is the author of Undermoney, a thriller about the illicit money that courses through the global economy.

Investors in emerging market sovereign debt are junkies — addicted to the illusion of higher yields. Truth be told, they’re also addicted to the adrenaline rush that comes from sitting at the high table to negotiate restructuring terms after a default.

For decades it has been past time for an intervention that recognises this addiction and helps us break the cycle of imprudent borrowing, feckless lending, and repeated restructurings that result in a race to the bottom: with sovereign debt being renegotiated and large chunks forgiven repeatedly until, magically, it disappears.

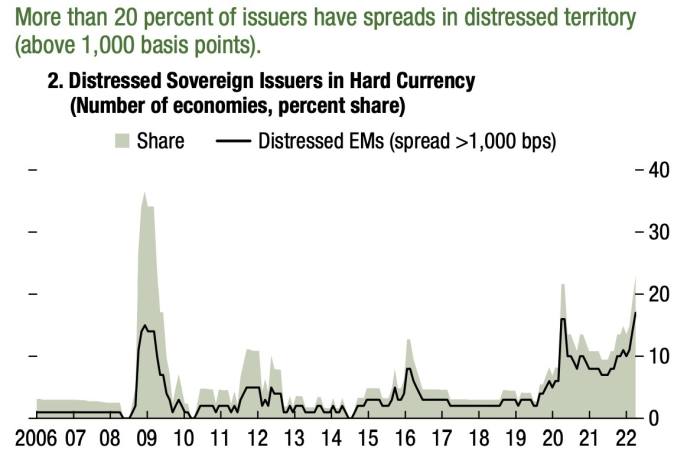

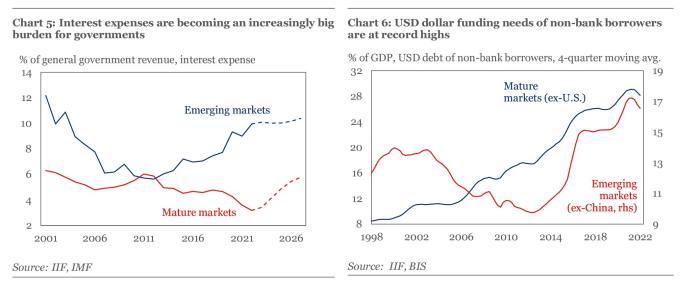

We are on the brink of an epidemic of emerging market defaults, the scale and scope of which will rival the debt crisis of the 1980s. Rate increases by Western central banks, fallout from the COVID pandemic, surging food and fuel prices resulting from the economic fallout of the war between Russia and Ukraine, mismanagement, and outright corruption all are contributing factors. No matter the causes, we will soon be in the thick of it.

Consider the warning issued recently by one of the biggest promoters of this sketchy asset class. According to JPMorgan, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, the Bahamas, Belize, Senegal, Rwanda, Grenada, and Ethiopia are all “at risk of reserve depletion” — a.k.a. the cash drawer is empty.

Let’s not leave out Lebanon, Egypt, Pakistan, Russia, the inevitable renegotiation of Ukrainian debt, or, for that matter, the 27 countries with bonds that yield more than 10 per cent — always a sign of trouble.

But, with all due respect to Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart: this time is different, because we are about to witness the first full-blown emerging market sovereign debt crisis in which a single lender — China — holds the whip hand.

China, because of the vast sums it has lent and invested through its so-called Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), controls the destiny not only of countries that have taken its money, but the IMF and private sector lenders we well.

Sri Lanka is a case in point. In 2019, the World Bank classified Sri Lanka as an upper-middle income country. Today, it has over $50bn in debt, but has depleted all its reserves, and its people are queuing for kerosene, food, and medicine.

There are plenty of explanations, but, not least, is the debt trap laid by China, which has in cahoots with the government saddled Sri Lanka with white elephants: uneconomic, ill-conceived projects like Hambantota Port and the empty Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport. When Sri Lanka, predictably, found itself unable to satisfy the debt, China sprang the trap, insisting on repayment, offering to exchange debt for further concessions and vast tracts of land, and offering additional cash to help tide the political class over.

If China was a run-of-the-mill commercial creditor, excessive borrowing would get sorted out. But it’s not. The size, scope, and terms of China’s BRI deals are state secrets. From all appearances, China not only intends to keep it that way, but to insist upon seniority — possibly even to loans made by international financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank.

What, then, is to be done? In the ordinary course, the IFIs, Western government, chuckleheaded NGOs, and the international press will call upon private sector creditors to offer Sri Lanka concessionary terms — to forgive a large percentage of their claims and extend maturities on rollover debt for decades.

Why do that? Unless a debtor demonstrates a willingness and capacity for reinvention, and unless all creditors — including China and the IFIs — agree to disclose the entirety of their claims and agree to negotiate a resolution on commercial terms, any restructuring will fail.

In place of such a flawed, conventional approach, private creditors should heed the mantra that has been good advice for addicts in every walk of life: just say no.

Just say no: to negotiating before the debtor has a comprehensive, sustainable fiscal plan. Why would any creditor negotiate with a debtor that doesn’t have a credible plan to solve its fiscal problems?

Just say no: to negotiations until a comprehensive, good faith analysis of debt sustainability has been completed. Until Argentina broke the mould, negotiations over the level of debt that could be sustained over the long-term was a given.

Just say no: until any debtor that has been victimised by decades of corruption undertakes a radical effort to identify the culprits and recover ill-gotten gains. There is good reason to believe that, in nearly every sovereign debt crisis over the past forty years, countries could have been put on a sound financial footing if even a small portion of stolen money had been recovered.

Just say no: to negotiating before international financial institutions, like the IMF, indicate precisely how their own claims will be treated.

Just say no: until there is a semblance of political stability. It’s not too much to ask whether the people sitting across the table will be there in six months — or six years. There’s no point in cutting a deal with a government that won’t survive beyond the signing ceremony.

Just say no: to signing up for loan documentation that fails to provide robust legal rights and enforcement protections to creditors. The biggest failure of the most recent Argentine debt restructuring was that, rather than present the government with contractual terms that would have provided enforceable rights, creditors opted to forgive half the debt without any quid pro quo. For Argentina, repayment of its external debt has become optional, despite it being possible to create a “super” bond with dramatically stronger protections in the event of default. To date, bondholders have simply been too timid and fearful to try.

Just say no: to any negotiations in which China and similarly-situated lenders, like India, fail to produce complete sets of documentation for their loans and investments — and agree to participate in restructuring negotiations as a commercial creditors with rights no greater or lesser than those of any other lender.

Sound like a dream? Well, the first step in recovery from any form of addiction is reality testing: you’ve got to recognise that you have a problem, and accept that doing the same old thing over and over again will not produce a different result.

It won’t be easy. The geopolitical incumbents — sovereign states, IFIs, NGOs — have for too long viewed private sector lenders as the first flock to be fleeced when a default occurs, rather than as partners in devising durable solutions.

Not only that, some of the world’s largest money managers seem to have decided that their first allegiance is to some vague Davos-inspired notion of collegiality, rather than protecting their investors.

But there is really nothing to lose — or to fear. Unless and until debtors plagued by weak institutions and by corruption are held to account, a dollar borrowed will continue to be a dollar gained. They will suck in as much money as they can, whenever they can — whether from markets, from bribes, from the IMF, or from China — and hide behind the notion that events spiralled beyond their control.

In the end, there is only one rational, functional response to the implicit argument that there is no dishonour in default. If you’re invited to participate in a process that is fundamentally flawed and corrupted: just say no.

[ad_2]

Source link