[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of Martin Sandbu’s Free Lunch newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Thursday

This week we released the second instalment of our occasional on-screen spin-off known as Free Lunch on Film. Do watch and share my attempts to explore and test my belief in climate techno-optimism — the view that it is possible to decarbonise the global economy without a radical change in our lifestyles. (And give a thought to all my colleagues and contributors who made the film possible!)

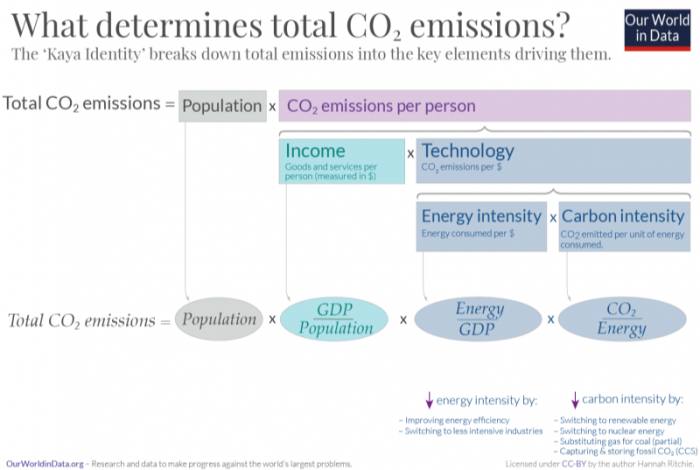

In this piece, I want to highlight some simple but powerful observations that play a big role in my thinking about this. Start with the wonderfully clarity-inducing Kaya identity, which simply sets out that total carbon emissions are equal to the multiplication of three or four relevant factors: carbon emissions per dollar of gross domestic product (which is, in turn, the product of carbon emitted per energy unit and energy consumed per dollar of gross domestic product), GDP per capita, and the number of people in the world. The website Our World in Data, from which I have taken the image below, has a good exploration of the actual numbers that go into it.

The Kaya identity shows that reducing emissions arithmetically requires either cutting the carbon intensity of GDP, making the average person poorer, or shrinking the population. In other words: green growth, “degrowth”, or a programme ranging from anti-natalism at best to eugenics at worst. So, taking as given that decarbonisation is necessary, which is it going to be?

In practice, decarbonisation will not mean literally zero carbon emissions. The “net” in “net zero” allows for emissions, combined with activities that draw carbon out of the atmosphere in the same amount. Planting more trees can do some of that, and I got my hands dirty planting one in the making of the film. One of my interviewees, the economist Arvind Subramanian, who used to be chief economic adviser to India’s government, emphasised that “negative carbon” technologies will have to be part of the solution. He argued that compared with renewables, we are investing far too little in such technologies, which include carbon storage in underground or subsea reservoirs, and the capture of CO₂ or other greenhouse gases at the point of emissions or directly from the air.

Now there is a lot of scepticism that negative carbon captures can amount to very much. But allowing for at least some carbon to be emitted on a “gross” basis, the Kaya identity tells us we may not need to cut carbon intensity, incomes or the population all the way down to zero — just almost all the way down to zero. Good thing too, because cutting either of the latter two literally to zero entails policies and outcomes that hardly bear thinking about and would, in any case. never be accepted.

But I do not think population control and degrowth are useful policy strategies even for more modest emissions reduction goals. Reducing the global population by an amount that makes even a dent in the carbon problem would require unacceptable control over people’s lives. As for degrowth, I think it is misguided.

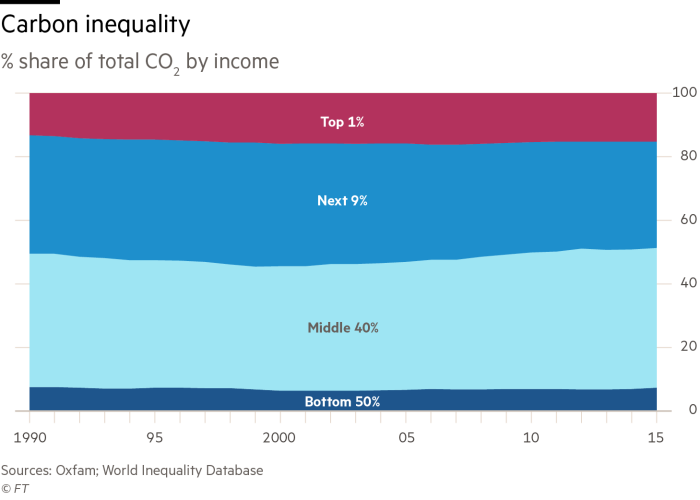

First, because letting poor people enjoy economic growth is no danger to the green agenda. Why? Because they emit so little at the moment that they could even engage in “dirty” growth for some time before making much of a difference. I admit I had not realised just how astonishingly unequal carbon emissions are. Diana Ürge-Vorsatz, an environmental scientist and a working group vice-chair at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, pointed out that the 10 per cent highest-income individuals in the world are responsible for half of the carbon emissions. The reverse is also true: the poorest half of humanity produces only 10 per cent of all global emissions.

Sensible degrowth advocates accept this, and suggest it is about rich-country residents (and presumably the rich in poor countries) reducing their consumption. But I find that unconvincing too. One thing is that it will not work unless the cut in material standards is draconian. In my interview with Branko Milanović earlier this year, he pointed out: “People don’t realise that the median income in western countries is at the 91st percentile of the global income, so even if you were to bring everybody in the rich countries to the median, which is actually for 50 per cent of people a loss of income, you would still not solve the problem.” And if you were to curtail the purchasing power of rich-country residents, Subramanian points out that through trade this would hurt poor countries too.

Sometimes people speak of degrowth as simply meaning to reduce material consumption — the physical stuff we emit carbon to produce. This can be done by shifting consumption from physical goods to services or simply leisure (working less), and it can be done by systemic change that reduces our material needs. One example is to design houses that need less heating or cities where you do not need cars much. But then we have really moved to talking about cutting the carbon intensity of GDP or income or wealth, not GDP or income or wealth itself. That is to say, green growth.

Is green growth realistic? To some extent it is already happening. A number of countries are already “decoupling” growth and emissions — the chart below shows how UK GDP and carbon emissions per capita have been moving in opposite directions. Decoupling is taking place even when accounting for the carbon embodied in production offshored to places such as China.

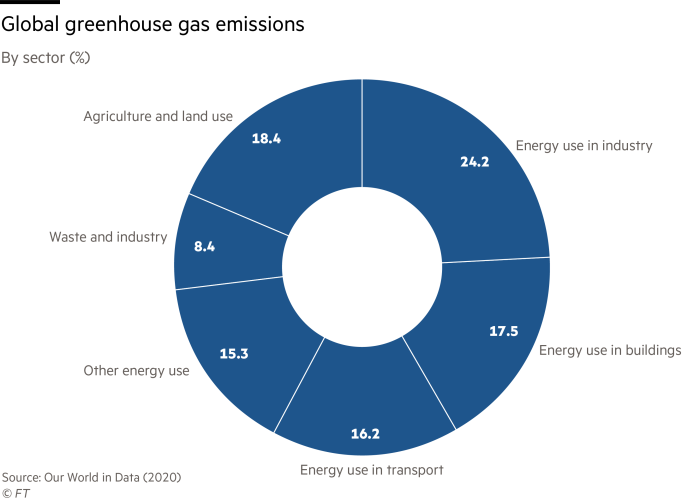

The question is not whether it is possible but whether it can happen fast enough, go far enough, and be done by enough (or all) countries. To form an opinion on this, look at where carbon emissions come from. As the chart below shows, it is mostly from energy use, in particular from industry, buildings and transport. Then comes farming and land use, industrial processes and waste.

In the film, we start by looking at transport, and visit Norway to look at the electric vehicle revolution there. The country has the world’s highest penetration of EVs; most new cars sold are electric. As the head of the EV users’ association, Christina Bu, told me, there is nothing natural about a cold country with long distances becoming an EV pioneer. So if Norway can do it — which it has done by taxing conventional cars and rewarding electrical ones — so can everyone else.

Here is what everything hinges on. I think what is possible for transport is true for other energy use: you can electrify almost everything, and you can decarbonise that electricity generation. (The challenge here is aviation and to some degree shipping, but even there zero-carbon technology is advancing.) For the remaining sources of emissions, things such as alternative building materials (high-rises made of wood rather than steel and cement) or high-tech agriculture and reforestation are part of the solution. The point is this: the technology exists to decarbonise almost everything our material lifestyles depend on and decarbonisation is therefore compatible with maintaining those lifestyles.

Two caveats are in order. The technology to take us to net zero could still deplete other resources (rare earths needed for batteries, for example) or cause other environmental problems. The techno-optimistic argument here is only about net zero carbon. And while it is technologically feasible to decarbonise our lifestyles, it will still be expensive. The International Energy Agency puts the needed annual investment at $4tn, nearly 5 per cent of current global GDP. We will not get there without a carbon tax, which will feel like it deprives us of economic wellbeing. And many carbon-intensive jobs will be lost.

But while raising investment must reduce consumption today, it will increase consumption tomorrow (the relevant benchmark is the risk to living standards if global climate change is not reined in). Carbon tax revenues can be redistributed as dividends, benefiting those most in need. And if recent IMF research is right, the job churn is not as bad as it was during deindustrialisation.

Above all, all of this is compatible with more and more people enjoying rich-country middle-class lifestyles. It will be difficult to get to net zero, but it will not be painful once there.

Other readables

Numbers news

-

The US released new inflation numbers yesterday. A tip: high inflation is baked into the year-on-year number because prices rose fast earlier in the year. Month-on-month inflation fell by three-quarters to 0.3 per cent, largely because energy goods prices went down. Service price inflation picked up strongly, however, reflecting the indirect effects of earlier jumps in goods and energy prices.

[ad_2]

Source link