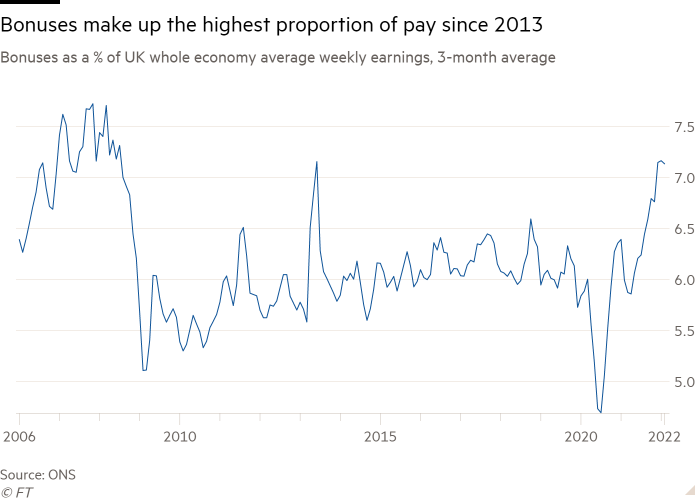

Bonus payments stand at their highest since 2013 as a share of UK earnings, as employers seek ways to pay workers for higher living costs without committing to inflation-busting wage deals.

Andrew Bailey, Bank of England governor, warned last week that intensifying pay pressures were one of the main reasons the central bank was worried high inflation would persist. “The first, second and third thing they want to talk about . . . is the tightness of the labour market. The challenges they’re having in recruitment and what that means for pay,” he said, referring to feedback from business leaders.

Underlying wage growth was already running at an annual rate of around 4 per cent: well above pre-pandemic levels, although far short of inflation, according to the BoE. It warned that it was likely to pick up further over the next few months because many companies were considering awarding mid-year top-ups to pay settlements or one-off bonuses to help them retain staff.

The latest official data suggest employers have increasingly been using discretionary awards to compete for scarce workers, while trying to limit the overall rise in their wage bill.

Bonus payments made up around 7 per cent of average weekly earnings in the three months to February, the highest proportion since 2013. This was partly owing to a bounce-back in bankers’ bonuses, after a lean year in 2021, but pay experts said the trend also extended to sectors where big bonuses are less typical.

British Airways last month adopted practices used last year by employers struggling to hire HGV drivers, nurses and warehouse workers with the airline offering new cabin crew a £1,000 welcome bonus as it seeks to address staff shortages that have forced it to cancel thousands of flights.

Duncan Brown, an independent adviser on reward management, said the use of sign-on bonuses and retention payments in these sectors and other industries, such as hospitality, was “unprecedented”. In professional services bonuses were increasingly being guaranteed rather than linked to performance, he added, while big tech companies were also relying more on cash bonuses because falls in their share prices had reduced the value of stock options.

“Pay awards are definitely only part of the picture at the moment,” said Sheila Attwood, a managing editor at the HR research firm XpertHR, who has seen many companies offering new recruits higher salaries than incumbents, while awarding time-limited “market supplements” to staff with key skills on top of the base pay rise offered to all employees.

Neil Carberry, chief executive of the Recruitment & Employment Confederation (REC), said many companies were offering staff more flexibility around homeworking as a way of addressing cost-of-living concerns. It cuts commuting costs so “in this environment hybrid is more attractive,” he added.

However, pay experts said employers were increasingly accepting that they would need to bring their basic pay awards closer in line with inflation — given mounting evidence of people on low incomes missing meals or falling into debt to pay for essentials as living costs climb.

“Most organisations have recognised that the typical 3 per cent annual raise is not going to cut it this year,” said Tom Hellier, an adviser on rewards at the HR consultancy Willis Towers Watson.

Brown added: “If anything now, the emphasis is shifting back from variable to fixed pay.”

A monthly survey of recruiters, published by the REC on Thursday, showed the proportion reporting higher starting salaries for both permanent and temporary staff remained near record levels in April.

Carberry said this showed “how broad-based” pay pressures were across the economy. Given the scale of the squeeze on household incomes, for most companies, the pre-pandemic norm of a 2 to 3 per cent annual pay deal “doesn’t feel sustainable”, he added.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.