[ad_1]

Immediately after concluding his first monthly monetary policy meeting as chancellor and raising interest rates by a quarter point to 6.25 per cent, Gordon Brown dropped a bombshell. The first monetary policy meeting of the new Labour government with Bank of England governor Eddie George was also to be its last.

From that moment on May 6 1997, the BoE would be independent to set interest rates through its newly created Monetary Policy Committee. Now, 25 years later, the independence of the central bank has not been seriously questioned under five prime ministers and six chancellors of the exchequer.

“It’s amazing how [BoE] independence has become part of the [UK’s] institutional furniture,” Ed Balls, then Brown’s adviser and architect of the plan, told the FT.

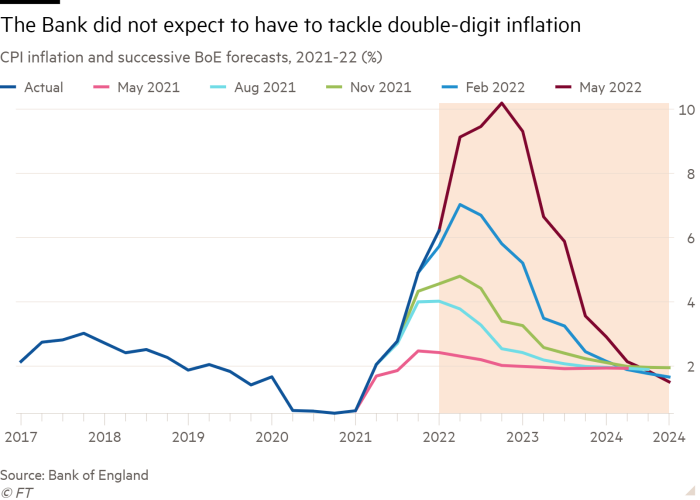

But with UK prices likely to rise at their fastest rates in over 40 years as sustained double-digit inflation becomes possible for the first time since the 1970s, former officials and economists say the independent BoE faces challenges that it has not encountered the past quarter of a century.

These include preventing inflation from spiralling out of control; avoiding distraction by fashionable ambitions, such as tackling climate change and inequality; ensuring transparent policy debate; and maintaining the legitimacy of its unelected officials to take the steps needed to defend the stability of the financial system.

Lord King, governor between 2003 and 2013, insisted that the process of granting the central bank more autonomy from the early 1990s to full independence to set interest rates in 1997, was a success and enabled the BoE “to have an independent voice and one for which it was accountable”.

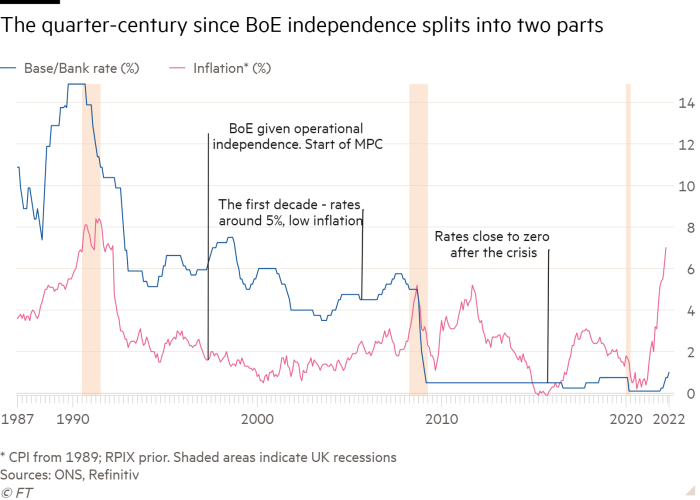

The central bank’s post-independence history splits into two broad periods. The first decade was one of apparent triumph, with financial markets’ reassured that New Labour would not be profligate with the public’s money and generate inflation.

Government borrowing costs declined, giving Brown more room to raise spending on social welfare and other priorities, while economic growth was strong and inflation stayed within 1 percentage point of the BoE’s inflation target.

Such was the strength of the economy that Brown regularly boasted of not returning to “boom and bust”. On the 10th anniversary of independence in 2007, King said, “it is not, I believe, credible to dismiss [the good economic performance] solely as the result of luck”.

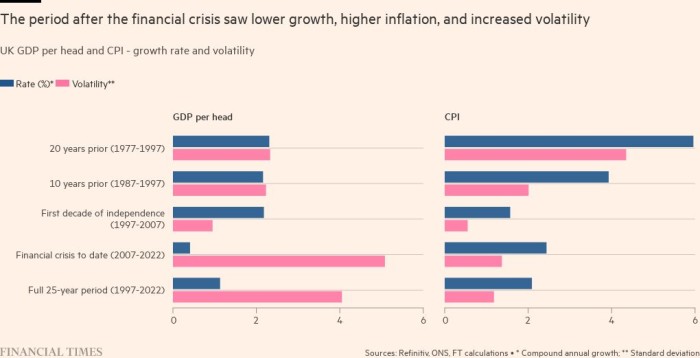

However, the good times did not last. Economic growth per capita, which averaged 2.2 per cent a year in the UK over the first decade of BoE independence, has slumped to average just 0.4 per cent a year since.

The economy suffered huge recessions following the global financial crisis in 2008-09 and the coronavirus crisis in 2020, which sandwiched years of grinding austerity as the UK faced up to being poorer than everyone hoped. Now, it faces a fourth shock following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which is pushing inflation higher and creating a cost of living crisis.

Inflation has been much more volatile than in the first decade, briefly spiking above 5 per cent in 2008 and 2011 and threatening deflation after 2014 before climbing to 7 per cent in March this year. Price rises are now heading towards double-digit rates not seen since the oil price shocks of the 1970s.

Mark Carney, governor between 2013 and 2020, said uncertainties over how far productivity growth had fallen — and whether this was permanent — made monetary policy much more difficult to manage.

“The extent [productivity growth] went away was an open question . . . and then we had a prospective supply shock because of the Brexit decision that was relevant for monetary policy over our forecasting horizon,” he said.

Over the 25 years as a whole, however, the inflation record is good, according to Jagjit Chadha, director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research. “However you measure it, [MPC members have] hit their inflation target and this needs to be remembered amid all the criticisms — it tells us something about the value of having experts involved,” he said.

King famously described the UK’s economic performance in the 10 years to 2003 as the “nice decade”, which he said was a warning that the good times could not last. “If we’d not had independence, there would still have been a global financial crisis,” he told the FT.

But the central bank did face serious criticism in the wake of the crisis. George Osborne, chancellor between 2010 and 2016, believed that the UK authorities’ failure to supervise its financial system adequately before 2007 required the BoE to have more power to regulate banks and the financial system, and a new governor, Carney, not tainted by the crash.

With poor economic performance, accusations of flip-flopping guidance on interest rates and allegations of politicisation in the Scottish and Brexit referendums, scrutiny of the BoE has only increased in recent years.

But it is Andrew Bailey, the governor since 2020, who faces the most difficult task of leading the central bank through a period of renewed inflation, according to former officials and external analysts.

After the Lords’ economic affairs committee last year accused the BoE of having a “dangerous addiction” to quantitative easing and pumping up spending each time things looked difficult, the central bank needs to decide how quickly to withdraw stimulus to rein in inflation.

“I think this is a big moment for [central banks] because they really have to demonstrate that they are determined to restore price stability,” said King. “It’s too late to argue that we’ve got a few months of high inflation and it will go away — it’s more a question of a few years,” the former governor said.

Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former member of the MPC, believes the BoE has little choice but to raise interest rates even if it generates a recession at a time household incomes are squeezed by higher energy prices.

“If real-income [declines] drove inflation cycles, we wouldn’t need monetary policy,” he said. “The whole reason you need a monetary policy-induced recession — probably necessary in the UK — is that the real-income effect doesn’t diminish inflation unless and until labour market conditions ease.”

Paul Tucker, former deputy governor and author of Unelected Power, a book that questioned whether central banks have been given too broad a remit, thinks the BoE can address the challenge of higher inflation if it sticks to its core purpose.

“Independence was a success, which wasn’t blown away by the global financial crisis,” he said. “But the BoE does now need to be focused on controlling inflation and stability of the wider banking system and that is it.”

But there is concern that the BoE is shying away from holding the same open and public debate about difficult economic issues it did when it first become independent, possibly undermining public confidence that its independent officials will address tough choices in ways politicians would avoid.

When inflation is heading towards double digits, Chadha said, “the MPC is far too quiet” about airing the big issues in public. Balls agreed that “over time, the [monetary policy] debate has become more muted” and that it would benefit the public to see the differences between experts aired in public.

But as the independent central bank hits its 25-year anniversary, there are almost no calls for government to take back control and few think politicians would risk removing independence.

“You can never take anything for granted,” said Carney. “But I think the structure of the MPC — enshrined in legislation, with explicit processes and personal accountability — greatly reduces that risk”.

[ad_2]

Source link