[ad_1]

No one has the right to a bank account. But once you have been accepted by a bank you might assume your account is yours to keep so long as you remain solvent.

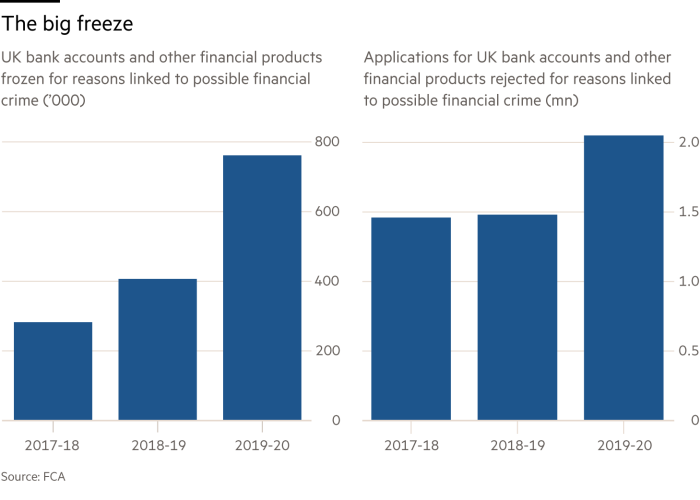

But this is not necessarily true. More than three-quarters of a million UK customers in in the 2019-20 financial year lost access to their accounts at banks and other financial companies.

Banks are freezing accounts in response to a spate of laws since 2000 to counter fraud, money laundering and terrorism. Technology advances have supported the introduction of more and more sophisticated automatic security checks.

These doubtless help to catch criminals. But they also ensnare growing numbers of innocent people who find their accounts frozen and access to their own money blocked.

This is not fair or reasonable. While the fight against financial crime must be fought — and fought hard — banks must do more to stop disrupting the affairs of innocent clients. In particular, they need to do far more to keep customers informed when their accounts are frozen — and move much more quickly to resolve issues when they can.

Fully 30-35 per cent of the 750 cases involving frozen accounts referred so far in 2022 to the Financial Ombudsman Service (FoS), the main complaints investigator, have been resolved in the customer’s favour. That is far too many.

Often, clients are given no reason why they have aroused a bank’s suspicions. But it seems that interventions are frequently triggered by unusual behaviour — such as a large deposit arriving into an account, especially when coming from abroad. Or by apparently trivial breakdowns in communications, such as a customer changing their address and failing to inform a financial company in good time.

Every week, I hear from readers caught out by having their bank accounts closed or frozen. They range from a young student who could not pay his tuition fees or accommodation costs to successful business people who do not know how they have fallen foul of bank algorithms to detect suspicious transactions.

Judging by reader complaints, customers are left without access to their money and no means to pay their bills. Direct debits and standing orders do not get paid.

I don’t deny that banks have a vital job to do preventing money laundering under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. They have to watch for suspicious transactions and block criminals paying stolen money into their own or other people’s bank accounts.

Clearly they are working hard. On Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) data, 761,437 customers were “exited” from banks and other financial firms in 2019-2020, the latest year for which figures are available. The numbers have more than doubled since 2017 when the information was first collated, with retail lending and banking accounting for most customers terminated.

But are the banks doing enough to help innocent customers resolve issues?

The pandemic has made it more difficult for clients to respond quickly to bank queries. A typical request is to ask customers to visit a branch of the bank with proof of their identity. Reduced banking hours and the inability to return to the UK from many countries during the pandemic stopped customers from complying. With Covid interfering with travel, FT readers working abroad or with second homes outside the UK appear to have had particular problems.

One FT reader, working in Australia, found it impossible to travel to the UK. He was left without access to his money for months. In other cases, customers with paperless banking were sent letters by their banks asking for ID. The post went astray and the customers did not know anything was required.

Once an account is frozen, it is not always easy to have it thawed or to open a new account subsequently. It is better to pre-empt closure by reporting any unusual transactions in advance. UK Finance, which represents UK banks, says. “We would suggest that people should contact their bank if they know they will be receiving a large sum of money.”

At the same time, banks must adhere to legal requirements which may stop them from sharing information with the customer, lest they inadvertently tip off a fraudster. This means you may not be told why your bank has blocked you.

UK Finance says: “Any decision to close an account is only taken after extensive review and analysis of the account.” But that’s a small consolation if your funds are in limbo.

Together with the FCA and individual banks, UK Finance has worked on improving how banks communicate with customers when they stop providing banking facilities.

But this is not enough. Martyn James of Resolver.com, the online financial complaints service, says your bank what is happening “in almost every set of circumstances. But because of a fear of anti-money laundering penalties most people are left with no explanation”.

If customers lose money or are inconvenienced by the freezing of an account the FoS may order compensation. It says: “In most cases, we’ve found banks have acted correctly in freezing the account but have taken too long or caused their customer detriment that could otherwise have been avoided.” In such cases, it often asks the bank to pay compensation.

Where the bank has acted “unfairly by freezing the account in the first place”, the ombudsman says it asks the institution “(where appropriate) to put the customer back in the position they would have been had the account not been frozen in the first place.”

But after-the-event compensation can be little help for people who have had their personal or business lives turned upside down. It’s for banks to do more to keep clients informed — and to do so much sooner.

Lindsay Cook is co-author of “Money Fight Club: Saving Money One Punch at a Time”, published by Harriman House. If you have a problem for the Money Mentor, email money.mentor@ft.com

[ad_2]

Source link