[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. We are not going to say a word about Will Smith and Chris Rock. There’s enough market violence around to give us something to gawk at. Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Tina still in effect?

One reason to own stocks, we have been told with soul deadening regularity for years now, is that returns on bonds are so terrible. This is the Tina argument: buy stocks, because There Is No Alternative. Well, returns on bonds are getting better. So presumably we have less of a reason to own stocks?

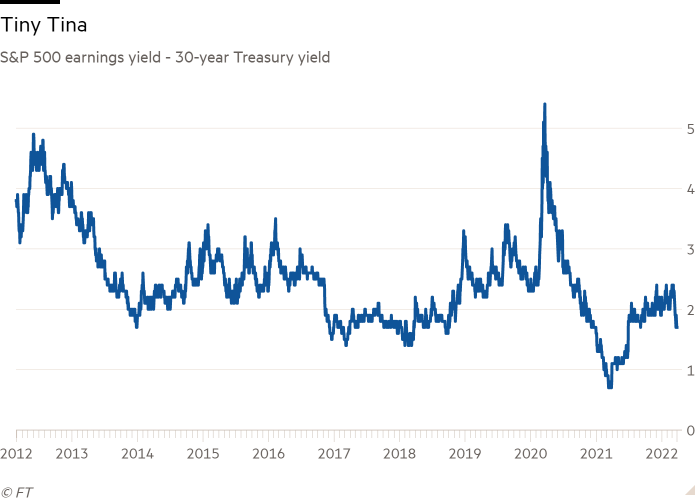

The yield on the 30-year bond is up to 2.57 per cent, almost a full percentage above the low it touched in December. Meanwhile, the earnings yield on the S&P 500 (earnings/price), at 4.3 per cent, remains well below long-term averages, and has been falling steadily for two weeks. Here’s a chart of the difference between the two over the past 10 years:

As you can see, what we might call the Tina spread has only once in the past decade been significantly tighter than it is now. In the first half of 2021, a jump in Treasury yields combined with a furious stock rally to push the spread briefly below 1 per cent. It didn’t last.

I’m not particularly confident that there is a deep economic, market-technical, or psychological logic that prevents the earnings yields from approaching Treasury yields too closely, other than the simple-minded notion that investors prefer high risk-adjusted prospective returns to low ones, and will move their money around accordingly. Maybe that’s logic enough.

And there does seem to be some correlation between the Tina spread and stocks’ performance. Here is a chart from Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research, showing that big corrections in the stock market are uniformly preceded by statistical extremes in the Tina spread — that is, moments when the spread hits extremes relative to its own 3-year history (Harnett uses 10-year yields, not 30s, but I doubt it makes a huge difference):

Note that the Tina spread does send false alarms — look at the mid-1990s, and arguably 2019, too. Harnett writes:

When you see a big move in the Z-score (today’s level vs three-year average all scaled by the volatility of the series over the same period) then the market can’t cope. Either bond prices or equity prices have tended to have moved beyond where fundamentals can justify and tend to ‘pause’ to wait for the fundamentals to catch up, or reverse if there is a sudden realisation that fundamentals cannot justify the move . . .

Like any of these [market] measures the danger is in asking [Tina] to work every time — they are part of an arsenal of different measures — but have tended to be pretty powerful over the last 20 years or so that I have used this approach.

We are not at an extreme Tina moment yet, but we should watch carefully if bond yields and stocks continue to rally together.

One tricky point at the current moment, though, is inflation risk. Inflation is bad for stocks; it is far worse for bonds. If we are worried that inflation might spiral up from here, investors might want to keep their allocations to equities high even as bond yields grow increasingly tempting in relative terms. In other words, might it not be that when inflation risk is high, a tighter Tina spread becomes more tolerable to the market?

The BoJ stares down the bond market

The yen has become very cheap, very quickly. In just three weeks, the yen has weakened 8 per cent against the dollar, to a seven-year low — lightning speed for currency markets. Adjust for inflation and weight by Japan’s trading partners, and the yen is a hair away from its all-time cheapest level.

The obvious culprit is the Bank of Japan. The central bank’s yield curve control policy commits it to holding Japan’s 10-year yield below 25 basis points. But a global interest rate raising cycle is afoot, luring capital out of low-yield economies like Japan. Investors are moving out of the yen, in part by dumping Japanese government bonds. So the BoJ is staring down the bond market, promising the 25bp peg is for real, even as investors bet it isn’t. No matter how much investors sell, the central bank says it will keep buying. Monday’s bond market action made the tug of war unmistakable. From Nikkei Asia:

The BoJ first announced one-time fixed-rate purchase operations after the yield on 10-year JGBs hit 0.245 per cent, approaching the BoJ’s target ceiling of 0.25 per cent.

The yield then sank to 0.24 per cent, which meant the market price for the bonds topped what the BoJ was actually offering, and the bank later announced it had no takers on its morning offer.

But continued selling pressure lifted the yield to 0.25 per cent later that afternoon. The BoJ responded with a second offer and ultimately purchased 64.5bn yen ($528mn) worth of JGBs.

Still, the yield refused to budge, prompting the BoJ to announce the same purchase operation starting from Tuesday to Thursday.

Or in chart form:

The BoJ’s bind is that it wants domestic consumer inflation, even as it gets too much producer inflation imported from abroad. Commodity inputs are soaring all over the world, but Japan Inc can’t pass those costs on to Japanese consumers, as Craig Botham at Pantheon Macroeconomics shows in this chart:

With consumer inflation sluggish and deflation fears still fresh, the BoJ really does not want to raise rates to stop producer price inflation.

Why can’t Japanese companies simply raise prices? Social institutions seem to be key, notes Karthik Sankaran, a forex strategist at Corpay. Japan’s less adversarial collective bargaining system and baked-in expectations of gentle price increases (or none at all) make passing on costs tricky. The BoJ has talked for years about setting off a wage-price spiral, with few results. So more expensive inputs will come out of corporate profits instead.

It’s not all bad news for corporate Japan. Many of its biggest businesses are export-oriented, and get a competitive edge from a weaker yen. Since the yen started weakening earlier this month, MSCI’s index of Japanese car stocks has shot up 10 per cent. Other exporters like Nintendo and Canon have gained, too.

But it is more bad than good. Botham thinks the growth and deflationary pressures are big enough to prompt further monetary easing. But that doesn’t mean the 10-year yield needs to stay fixed at 25bp. A slight loosening to 50bp could buy the BoJ some space. Here’s Botham:

We think this could be done without tightening domestic financing conditions, given the multiple funding schemes under the BoJ’s purview. A partition between [bond] yields and financing for [small and medium enterprises], for example, should be feasible. A policy shift seems likely this quarter, if the pressure on oil prices and the yen does not abate.

As long as the BoJ stays the course, “we’re going to be testing whether or not Bank of Japan policy has changed because now there is no room for manoeuvre”, said Pelham Smithers of Pelham Smithers Associates. This is high market drama, which seems to be the order of the day just about everywhere. (Ethan Wu)

One good read

Adam Tooze is on the front page of this week’s New York magazine. Folks can’t get enough of him. As it happens, he will also appear in Thursday’s Unhedged.

[ad_2]

Source link