[ad_1]

US-domiciled exchange traded funds that were so cheap they stole market share from rival ETFs five years ago are now seen as so expensive they are bleeding assets to challengers charging even lower fees.

The trend is a sign of continuing fee compression in the $7.2tn US ETF industry as increasing competition forces fund groups to cut costs or haemorrhage market share to more aggressive rivals.

“The goalposts haven’t just shifted. They moved from one end of the field to the other,” said Elisabeth Kashner, director of global fund analytics at FactSet.

“In December 2017, the asset-weighted average expense ratio for ETFs that had gained market share from their direct competitors was 0.19 per cent, while the losers cost 0.26 per cent. By December 2021, 0.19 per cent was the price tag on market share losers. Successful funds now cost 0.16 per cent,” Kashner said of the US market.

“Investors have been flocking to lower-cost options across most segments of the ETF landscape. As a result, asset-weighted expense ratios have been falling across asset classes and strategies.

“Investor preference for the lowest-cost products has become entrenched.”

Similar trends are in play elsewhere in the world, even if the absolute level of fees tends to be lower in the US market, which is the most mature and best placed to harvest economies of scale.

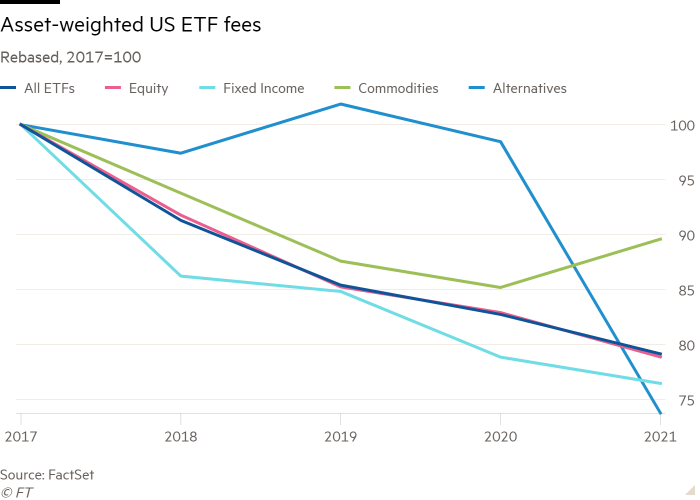

Average asset-weighted fees for fixed income ETFs in the US have fallen from 15 basis points to 13bp since 2017, FactSet found, with those for equity funds slipping from 17bp to 14bp over the same period.

While they remain more expensive, fees for ETFs following narrower asset classes have tumbled faster still, with those for alternative assets down from 89bp to 67bp in the past year and fees for geared ETFs sliding from 102bp to 71bp, although currency funds managed to buck the trend.

“Asset-weighted expense ratios have been falling across asset classes and strategies. No matter the starting point, the destination is the same,” Kashner said. “There is no place to hide, no matter the asset class or strategy.”

Investors may be able to look forward to many more years of falling charges to come. Kashner believed fees will ultimately fall to fund providers’ marginal cost of production which, ultimately, would be 1-2bp for the “biggest broadest funds”.

Over the past year the slide in US ETF fees has been most striking in the fast-growing field of actively managed funds, which do not passively track an index. Average asset-weighted fees have tumbled to 49bp from 72bp in 2020 and 89bp in 2017.

Last year’s data was distorted by Texas-based Dimensional Fund Advisors’ decision to convert six mutual funds with combined assets of $20bn into ETFs, which artificially lowered the average fee, given that they all charge less than 20bp.

“They chose a pretty aggressive price point for their funds. Because they converted such a large asset base, they lowered the average,” said Kashner. Yet she did not believe active management was immune to the wider fee war.

“We have seen evidence for fee compression in actively managed ETFs for quite some time, irrespective of the entry of Dimensional. It has followed the pattern that we have seen in other areas,” she said.

Ever-lower fees may not be unalloyed good news for investors, however. One concern may be whether fund managers realistically can be expected to engage effectively with investee companies on ever skimpier revenues.

Average fees for equity ETFs investing on the basis of environmental, social and governance (ESG) concerns have halved from 38bp to 19bp since 2017, for instance, FactSet found.

However, Kashner believed meaningful engagement was still possible, given the economies of scale large fund houses, at least, are able to deploy, even though there are between 3,000 and 5,000 US equities that are large and liquid enough to be investable by mainstream funds.

“The largest asset managers have been managing proxy voting for decades. Most of the big groups already have an in-house operation. That’s an area where scale really matters,” she said.

Kenneth Lamont, senior fund analyst for passive strategies at Morningstar, said the market had been shaken up by market leader BlackRock aggressively cutting fees for many ESG ETFs. This had removed the possibility for the industry-wide excess profits that typically exist for a few years for new products, until competition whittled them away.

Nevertheless, he believed ESG engagement was affordable, even as fees become more compressed.

“Engagement is not free, ESG is not free and let’s be honest, the margins on these products are very low. However, it’s a scale game,” Lamont said.

“If you have six people working on these engagement efforts, that is not going to break anybody’s bank,” he said. “Engagement is becoming a differentiating factor.”

Another downside from falling fees may be a rise in industry concentration, if only fund shops with sufficient scale can afford to compete.

Although the triumvirate of BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Global Advisors dominate the US market, Kashner said concentration had held steady or even fallen a little over recent years in some segments as several mid-level players, such as Ark Invest, had gained market share.

Lamont warned that “generally speaking, monopolies have not worked out very well in any industry”.

However, he believed “we are a long way away” from such a scenario.

“Falling fees in the ETF industry are one of the most positive developments in asset management over the last 20 years,” Lamont said.

“The [small] amount that you have to pay now to access markets that you didn’t even have access to before. The doors that have been opened to you and the cost reduction in the asset range is enormous. It really is a success,” he added.

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

[ad_2]

Source link