[ad_1]

The benefits of investing using Isas may not be truly appreciated until later life, when you can harvest your tax free dividends and investment gains without a penny of tax to pay.

However, a growing number of investors want their tax relief up front — and are willing to stomach increasing risks to get it.

As the end of the tax year approaches, the rush to invest in venture capital trusts (VCTs) is on. A record £1bn is expected to flow into funding young, fast-growing UK businesses in the year to April 5, according to investment platform Wealth Club, which says current inflows are £20mn a week.

Selling tax breaks to investors is clearly big business, but look beyond these benefits, and is the underlying investment case really that great?

So far this year, £886mn has been raised — some 75 per cent more than at this point a year previously, and the highest annual amount since VCTs were launched in 1995.

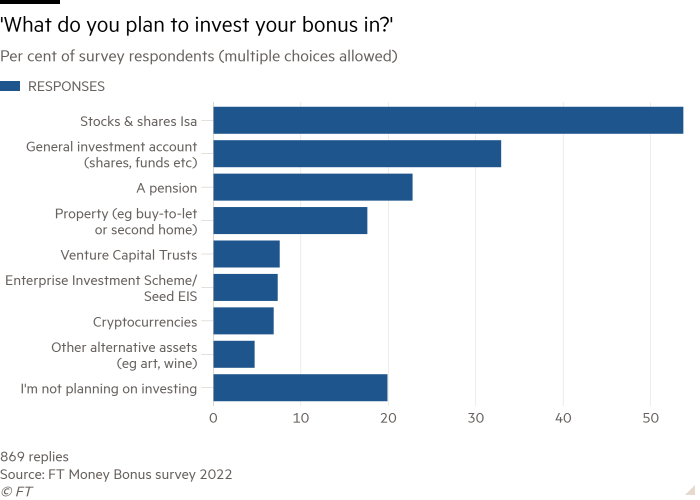

Having sifted through nearly 900 comments from readers who responded to the FT’s recent bonus survey, it’s clear that being “capped out” of pension saving is what’s really driving the growth of riskier tax-efficient investments.

VCTs and the enterprise investment scheme (EIS) are fast becoming mainstream investment choices, with just over 7 per cent of FT readers in our poll intending to invest some bonus money into them — many of them for the first time.

In return for committing to an investment over several years in qualifying early-stage UK companies, investors can benefit from upfront tax breaks of 30 per cent, and up to 50 per cent for riskier Seed EIS (SEIS).

The precise rules, annual limits and benefits vary, but can include tax-free dividends, tax-free growth and potential inheritance tax advantages — plus “loss relief” if investments fail. All of this helps investors to tolerate the other thing these investments have in common — hefty fees.

Readers are wise to this. While VCT fees are high, one commented, at least the trust structure forces managers to be transparent about charges. What he struggled with was assessing the ability of specific managers to deliver investment returns that might justify these costs — a primary concern when making illiquid, long-term investments. Could I offer any further thoughts?

Before we even consider the ability of a fund manager to pick winners, what concerns me most about VCTs is their recent popularity.

Years ago, when I started out on the Investors’ Chronicle, these investments were a pretty niche choice. Now a £1bn industry, stiff competition to invest in the companies of tomorrow is pushing up prices and stretching valuations of the early-stage businesses fund managers target, which cannot bode well for future returns.

“There’s only so many good growth businesses that managers can invest in, so they’re going to be chasing prices up,” says Ben Yearsley, a seasoned VCT investor and director with Shore Financial Planning.

However, the strong past performance of VCTs has turned more investors on to their tax-free benefits. According to data from the Association of Investment Companies, VCTs delivered average total returns of 24 per cent in 2021, albeit after a rocky year in 2020.

For those eager to compare past performance of different managers, a free comparison tool on the AIC website helpfully lists total VCT returns over one, five and 10 years, plus stats about dividend growth and ongoing charges.

Yearsley has invested in multiple VCT and EIS raises since the late 1990s. Making up 15 per cent of his overall portfolio, he says his overall returns (net of fees) average around 7 per cent a year. “Factor in the tax breaks, and it’s closer to 10 per cent,” he says, adding that it’s nice getting the regular dividend cheques and not having to pay tax on them.

Considering the superior long-term performance of top Isa picks such as Fundsmith or Baillie Gifford trusts, you might be surprised that the “growth spurt” VCT investors target does not produce higher returns.

Those salivating about getting in early on “unicorns” such as Cazoo or Zoopla should remember the reason for the tax breaks — the risks. For every unicorn, there are hundreds of lame ducks.

The largely benign economic conditions of the past 10 years have generally been good for early-stage companies and the tech sector bias of many VCTs helped protect them during the pandemic. However, the outlook — and soaring inflation in particular — is more challenging, particularly on today’s generous valuations.

This brings me back to the fee impact. If the size of VCT assets under management is increasing at such a pace, can investors expect fund managers’ ongoing charges to fall? I doubt it.

The minimum £5,000 ticket size typically needed to access these kinds of investments means building up a diversified portfolio across several funds is expensive — not to mention illiquid, as the money has to stay invested for years, or else you lose the tax break.

One FT reader who responded to our poll says he has put £20,000 of his bonus into his Isa, and a further £20,000 SEIS, where the risk of backing ultra early-stage companies means investors receive even higher tax breaks of 50 per cent.

“I was attracted by the upfront relief, which means I’ll get £10,000 back when the money’s invested and my certificates come through, but I wasn’t aware of the benefits of loss relief which can be offset against future tax bills if these investments don’t work out,” he says. “Plus you never know — there’s a small chance I could hit on the next Uber.”

Yearsley cautions that because of the risks, the “natural route” should be VCT first, EIS next, and SEIS last. “I invested in one SEIS scheme with 36 early-stage companies, and 28 have gone bust,” he says. “I’ll probably get my money back over an eight-year period, but that’s due mainly to the tax breaks.”

More experienced investors may prefer to play fund manager themselves, targeting EIS investments into a single company of their choice, instead of a fund.

If you can stomach this concentration of risk, you will typically need £15,000 to £25,000, and introducer fees could be 5 per cent or more. But as Yearsley says, “a huge part of the appeal is getting involved. You can pick and choose the projects you invest in and will usually have access to management.”

He’s chosen to invest in his local brewery — he obviously likes the beer, but also feels good about jobs that are being created as the company grows — plus he hopes to double his money over eight to 10 years.

Importantly, he’s prepared to swallow the losses if things don’t go to plan. But I wonder how many investors piling into VCTs this spring have conducted such a sober assessment of the risks they’re running in return for a tax break.

Claer Barrett is the FT’s consumer editor: claer.barrett@ft.com; Twitter @Claerb; Instagram @Claerb

[ad_2]

Source link