[ad_1]

Facebook’s hopes of connecting everyone alive may have been frustrated after the social network recently shed daily users for the first time, but companies that specialise in tracing the dead are just getting started in their attempts to build vast global databases of lineages.

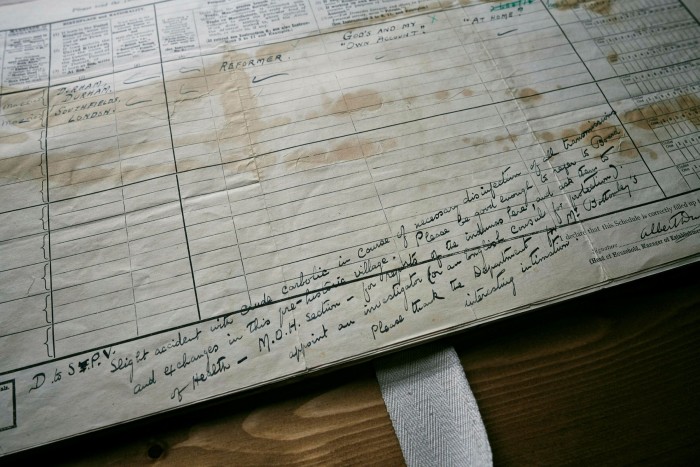

Genealogy websites, which surged in popularity during the pandemic when people stuck at home turned to researching their family trees, are about to digest terabytes worth of documents that will give them new insights into the past. The US government is due next month to publish seven decades-old records that until now have been locked away under confidentiality rules.

The 1950 census is a snapshot into an era when Harry Truman was in the White House, Walt Disney’s Cinderella was in movie theatres and America was at the onset of its postwar economic boom.

For the privately owned operators in the expanding ancestry industry, a lot is at stake.

The global trend for people to want to find out more about where they come from has become big business — illustrated by investment group Blackstone’s $4.7bn deal, completed just over a year ago, to buy Ancestry, the largest company in the sector.

The Utah-based company, chaired by former BBC director-general and New York Times chief executive Mark Thompson, is seeking to expand its base of almost 4mn paying subscribers and build a social network of genealogy enthusiasts.

Competitors include MyHeritage, based in Israel, which was acquired last year by private equity group Francisco Partners for about $650mn. Gilad Japhet, founder, said the forthcoming US census release — the first in a decade — would be a “momentous occasion” for the sector.

The publication by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) will allow descendants of the 152mn participants in the household questionnaire of 1950 to learn more about their roots.

For those who already have a good knowledge of all four of their grandparents the disclosures could be incremental, but some will discover previously unknown relatives and uncover old family secrets.

“Hardly anyone” in the country at the time of the survey would have slipped through the net, Japhet said, adding that enumerators even visited hospitals and prisons.

Although the release in three weeks is an opportunity for genealogy sites to woo new users, it will also bring scrutiny. Some family history specialists criticised transcription errors in the recent digital publication of the 1921 census in England and Wales, which Findmypast, another of the world’s largest family history websites and a division of Scottish publisher DC Thomson, had an exclusive contract to process. Findmypast said in a statement it was “continuously reviewing, cleaning, standardising and enhancing” the records.

The first postwar US census was conducted at the start of the baby boom and not long after hundreds of thousands of immigrants had arrived from war ravaged Europe, making its publication of interest to many families outside the country.

“We really want to make sure we get it right,” said Todd Godfrey, vice-president of global content at Ancestry, adding that the company had spent about two years preparing.

US 1950 census release by the numbers

152mn

Number of people included in census

72

Years detailed census information is kept confidential

6,373

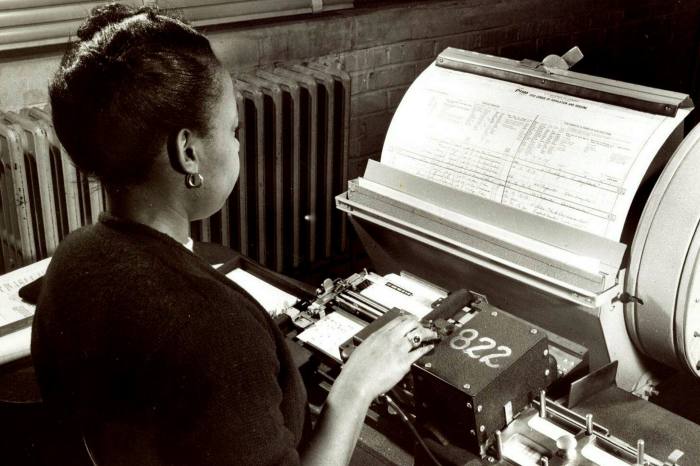

Number of microfilm reels scanned by NARA staff

The census will also be the first to be published since DNA tests to determine ethnicity became widely popular, despite some privacy concerns. While the results of the tests can “satisfy initial curiosity” in those who take them, they also tend to “open more questions”, said Scott Fisher, host of the Extreme Genes radio show and podcast.

Television programmes such as Who Do You Think You Are?, a series that documents celebrities exploring their lineage and has been adapted for several countries, have further encouraged the phenomenon.

Genealogy has become part of a trend for consumers to pay for online services on a recurring basis, even if it is a more niche pursuit than streaming TV shows or music.

Subscriptions are based on the premise that the story of an individual’s ancestry is not fixed and users will make ongoing discoveries as new records are made available.

Predictable cash flows were one reason why Blackstone had been eager to acquire Ancestry, said David Kestnbaum, a senior managing director at the investment group.

Users are prepared to fork out about $250 per year for access to Ancestry, whose revenues rose a tenth last year to about $1.3bn. “It’s really a giant data asset that monetises itself through these subscriptions,” Kestnbaum said.

Enthusiasts include Kathryn Doyle. Her interest was sparked in the late 1990s when her grandmother was talking about her great-great-grandfather, who served in the American civil war.

The conversation began what became a more than 20-year hobby. In pursuit of it, she has sometimes risen in the small hours to view newly disclosed records online, and visited the National Archives in Washington to inspect documents in person.

Doyle, now president of the National Genealogical Society, said she recognised that not everyone shares her passion. “Some people think it’s a total bore,” she said.

To access the records from 1950, users will not need to subscribe to sites such as Ancestry. NARA is planning to make them available for free online and searchable by name, thanks to Amazon optical character recognition technology.

However, the public might encounter errors, at least at first. The agency said the initial electronic transcriptions were unlikely to be perfect, describing it as a “first draft”.

The pitch from the genealogy sites is that their offerings will be more compelling than the government version.

For instance, people with common names could be particularly difficult to track down if that is the only way they can be searched for. Ancestry aims to allow users to also search by birth place, age and occupation, among other criteria. To do so, it is planning to index the census microfilm images using artificial intelligence independently of NARA, an exercise that is likely to take weeks.

The company is partnering with another Utah-based genealogy service, FamilySearch, run by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to conduct human checks and improve accuracy.

Crista Cowan, corporate genealogist at Ancestry, said the census could reveal only so much on its own and that if people wanted to understand more they would have to combine it with earlier publications.

“A census is really just a snapshot in time,” she said, adding that other sources were needed “to tell the full story”.

Whether that story is accessible to an individual depends on their ethnic background. Ancestry has a bias to users with western European heritage since records were more available in those countries, Kestnbaum said.

The company, like some of its peers, is seeking to acquire more records in other jurisdictions and in different languages to make its offering more relevant to a wider audience — not least given that the population in the US, its largest market, has a diverse background.

The 1950 documents will be the latest addition to what is already one of the more comprehensive archives for genealogists of any country, said Japhet of MyHeritage, partly as a result of a lack of wars on its territory, which have destroyed those elsewhere.

France, the UK, the Netherlands and Scandinavian countries also had good records, he added, but some of those elsewhere are more patchy.

Even if the creation of all-encompassing global databases of family trees remains some way off, Japhet said genealogy’s popularity as a pastime would endure.

“This is not a passing frenzy,” he said, adding that the subject has “been important to people for thousands of years”.

[ad_2]

Source link