[ad_1]

For investors, Britain is not just the sick man of Europe but of the world. Since voting to leave the EU in 2016, UK stock market returns have lagged behind international peers and a historically wide valuation discount has become ingrained. So much so that the UK has become a hunting ground for foreign buyers searching for cheap deals such as the US buyers of supermarket chain Morrisons and of defence manufacturer Meggitt.

This diminished position is not helped by comparisons to booming tech fuelled US markets. Internet giants such as Google, Microsoft and Apple have all achieved trillion dollar valuations at record high multiples. Yet Britain barely musters a mid-cap tech group. Software group Aveva valued at £7.5bn is currently the largest tech group in the FTSE 100.

And while the US market is packed with such racy growth stocks — companies that are often unprofitable but richly valued due to rapid revenue growth — the UK market is populated with profitable cash generating businesses or value stocks that have reached maturity.

Paul Marshall, chair of hedge fund Marshall Wace, believes the situation is now so dire that the UK risks becoming a “Jurassic Park” market — only fit for dinosaurs.

An imminent test of that will come when SoftBank-owned chipmaker Arm decides on whether to list in London or elsewhere after a $66bn deal to sell it to Nvidia was blocked by UK regulators. Broad estimates for the tech sector imply a 30 per cent valuation lift for Arm in New York.

If Arm were to surprise the markets and pick the UK it would offer some vindication of efforts to attract faster growing companies to London. Separate reviews last year by Jonathan Hill, the former European Commissioner for financial services, and Ron Kalifa, the former Worldpay chief executive, have led to more relaxed rules on dual class share structures and public share counts.

The tweaks, however, are unlikely to get to the heart of the problem: the UK stock market is cheap on almost every measure. Unless that changes, the implications for investment and innovation in the country could further diminish Britain’s international competitiveness.

Valuation gap

For an economy strongly tied to the financial services industry, which accounts for about 10 per cent of gross domestic product, it is embarrassing that the value of UK equities has fallen so far behind that of international peers. And it is not just investor returns that have lagged behind. The market as a whole and individual sectors continue to trade at valuation discounts.

Whether using the largest 100 companies in the FTSE or broader measures, the UK market has a substantial discount with the rest of the developed world. At the end of 2021, the valuation gap between the UK and other developed markets — almost 40 per cent on a forward earnings basis — was at its greatest in three decades, although it has since narrowed.

The reasons are varied but the decision to leave the EU in 2016 spooked investors who worried that trade with the UK’s biggest partner would collapse. The period after the vote is when valuations began to sharply diverge. The FTSE 100, valued at 16 times forward earnings in May 2016, was in line with other developed world markets. A year later a 14 per cent discount had emerged. It widened to 25 per cent by the end of 2019.

The vote’s impact is undeniable. But there is more to the story than just heightened political and economic risks. The structure of the UK market has been out of favour with investors for far longer.

“The perception is that the UK is a place of old economy businesses,” says Andrew Millington, head of UK equities at asset manager Abrdn. Heavy on banks, insurers, oil and miners, this view is “reinforced by the FTSE 100 and is something that predates Brexit,” he adds.

A benchmark weighted in favour of value or dividend paying businesses has constrained returns. These stocks tend to be steady state enterprises that generate reliable cash returns for shareholders but offer little growth. Even so, investors have limited interest. Shares in Barclays bank and energy group BP, for instance, remain stuck at 2016 levels.

Instead, investors want businesses they think will produce high revenue growth and the potential to dominate the markets of tomorrow. Most of these are technology businesses where profits can be non-existent. In fact many, such as electric carmaker Tesla, have required constant funding by shareholders to progress. Bets on the distant future are often easier to justify when interest rates are low and money is cheap.

Technology fail

Part of the UK’s underperformance is the underlying skeleton of the market. Technology groups dominate global growth as businesses compete to be the next Google, Apple or Alibaba.

The UK is barely in that race. The technology sector accounts for less than 5 per cent of the UK’s total market capitalisation. In Germany, it is 11 per cent. In the US, it is almost one-third. Investors fascination with growth has been fuelled by a record period of low interest rates. But as these start to rise the value of future cash flows fall as they are discounted to present value.

The UK began to trail other global markets, on a total return basis, at least two years before the Brexit vote due to this value bias in terms of the composition of stocks. And even if you adjust for that bias, the valuation discount shrinks but is still about 10 per cent, calculates Simon French, economist at Panmure Gordon.

UK listed companies have to therefore work harder and increase earnings faster to achieve the same stock ratings as peers elsewhere. “Failure to embrace a growth-oriented mindset is unnecessarily raising the cost of equity capital [in the UK],” says French.

Using price-to-earnings to growth (PEG) ratios, a metric that combines a stock’s valuation and its expected growth, French found the UK at 1.3 times was substantially below the EU at 1.7 times and the US at 1.9 times. “Eight out of 11 industrial groups [surveyed] across both Europe and the US have higher PEG ratios than their UK equivalents,” says French.

Software group Blue Prism typifies some of these failings. The maker of robotic process automation tools will leave the UK’s junior AIM market in a £1.24bn deal with SS&C of the US. That takeover price is well below where its shares were trading as recently as the beginning of 2021.

Blue Prism is not the only UK listed business that went to foreign owners at a perceived knockdown price. Takeover attempts were at a 14-year high last year and bids from private equity were at a record. Markets are telling investors that UK assets are a bargain but many buyers are simply not listening. If they were, valuations would be higher.

Looking for someone to blame

The findings from the Panmure Gordon analysis lend weight to Marshall’s criticism that UK money managers have become part of the problem. Income funds invest in the lower-risk, steady return, cash-generative businesses that make up much of the FTSE 100.

Such income funds only make up 5 per cent of the £1tn UK managed equity assets, according to the Investment Association. But, says Marshall, this income focus is more widespread than just these officially designated funds. He argues that the whole UK fund management industry has deep seated income bias that has become ingrained in investment mandates from pensions to insurance and other funds.

That creates a cycle of negative feedback that is cutting off the lifeline of new growth and keeping the UK market down. This thesis is only partially true. While the UK market is underweight in technology it has still created some strong performing businesses over the past decade.

“It has been possible to build good outperforming portfolios of growth stocks in the UK using an active strategy,” adds Millington. “The FTSE 250 index has some very exciting mid-cap growth businesses.” Share prices for retailer JD Sports and equipment hire group Ashtead have both risen more than 15 times over that period. Information group Relx has risen fourfold and is now valued at £43bn.

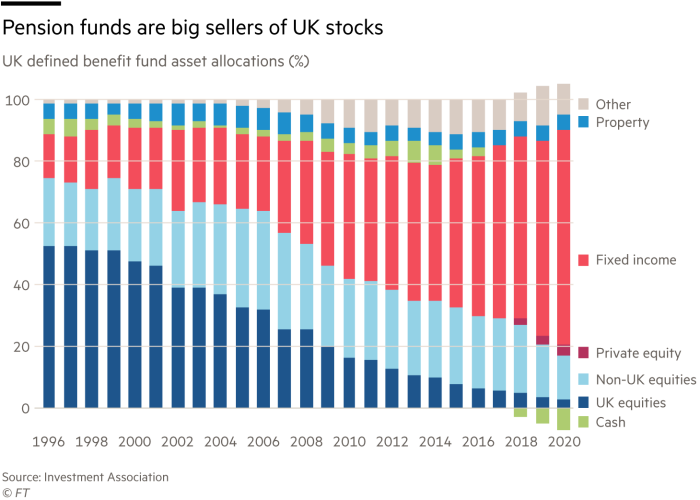

The shift from defined benefit, or final salary, to defined contribution pensions has been another key factor in lower valuations. “Systematic selling by DB funds has driven valuations for UK stocks lower,” says Professor David Blake, director of the Pensions Institute at Bayes Business School.

DB pension schemes in the UK have been big net sellers of equities globally in the past two decades. This is largely due to demographics as members age and savings are converted into more stable cash bearing assets such as bonds.

And although 80 per cent of the UK’s pension assets remain tied up in DB schemes, the bulk of these investments are now in bonds and other cash-generating alternatives such as property and infrastructure. The level of UK equities held within DB schemes has fallen from about half of total assets in the early 2000s to less than 5 per cent today.

“As schemes have closed to new members, allocations have shifted away from growth investments like equities towards income investments, like bonds,” says Matthew Graham, head of UK and multinational DB pensions at Aviva Investors, the asset management company.

Just a quarter of total UK pension assets — both DB and DC — are now in equities compared to about half in the US, according to advisory group Towers Watson. Not only are there fewer younger savers to step in for those whose pensions are moving into maturity. But allocations to UK equities for these new savers is far below historical levels. Any home bias that once favoured equity markets in saver’s own countries has mostly been eradicated as a result of cheaper costs such as currency hedging.

Changing demographics mean that not only is the total volume of new savers’ pensions lower but the share allocated towards the UK market is also smaller. Newer UK pension schemes are choosing instead to invest across equities globally. “Unlike DB schemes, our members carry the entirety of the risk. That gives us a greater incentive to maximise returns,” says Liz Fernando, deputy chief investment officer at the National Employment Savings Trust, which manages £23bn of workplace pensions.

Despite almost 60 per cent of NEST’s allocations being held in equities, roughly only 4.5 per cent is in the UK stock market. A choice that is difficult to argue with given the UK market’s underperformance in recent years.

While many developed countries face the same demographic and pension pressures, the UK appears to be suffering worse. “Weak productivity growth should not be overlooked as a factor that is holding the UK back,” says Blake.

Solving the problems

Awareness of the problems is growing. The UK’s lack of exposure to technology stocks was prominent in the Hill and Khalifa reviews. Changes to rules around dual class shares might encourage more listings. Yet, they are unlikely to be a factor for large businesses seeking the best valuation such as SoftBank’s Arm, for which the US offers a clear advantage.

That does not mean the situation is hopeless. In fact, the UK market has done better than most others so far in 2022. The FTSE All-Share index is still down but losses are less severe, especially compared with the steepest in the tech heavy US market.

The same factors that have depressed UK stocks for a decade are now working in its favour as a global rotation into value accelerates alongside the prospect of higher interest rates. These should be particularly beneficial to the banks and other financial businesses that are over-represented in UK indices.

Rising interest rates will boost banking revenues as interest margins expand. Higher rates also typically mean future cash flows are more heavily discounted by investors lowering the worth of growth stocks, which are valued on longer term horizons.

It is too soon to celebrate. There have been several periods of recent outperformance for value stocks: at the end of 2016 and 2018, and most recently at the beginning of 2021. All of which fizzled as growth reasserted its dominance. Is it different this time?

What has changed is inflation. This is now at a 40-year high in the US and the fastest for three decades in the UK. Predictions for the number of Federal Reserve rate rises in 2022, which set the tone for global markets, have risen from one or two at the end of last year to two or three in January, to five or seven now. But any rate rises could be slowed by the impact on the global economy of the war in Ukraine.

“Inflation will be materially higher in the next 12 months and central banks will be forced to act. At some point the switch from growth [stocks] into value [ones] will be real,” says Millington.

The ability of the UK market to take advantage of that depends not only on a favourable composition of value stocks. But is also evidence that these stocks are able to do what income investors are looking for, pay out cash dividends.

UK public companies paid out £100bn to shareholders in 2019. Growth in dividends had outstripped earnings pushing coverage ratios, which measure how well earnings support dividends, to record low levels. The pandemic forced many to reset. Shell, for example, cut its dividend at the end of 2020 for the first time since the second world war. That helped boost dividend coverage, which this year will be closer to two times earnings for the FTSE 100 than it has been since 2014, says AJ Bell.

The past decade has tested the resilience of the UK economy and its investors. A lack of large globally competitive tech businesses is a symptom of deeper problems that cannot be solved simply by quick fixes to listing rules. Problems that have been further exposed by the extraordinary performance of tech businesses in the US, China and elsewhere. But as that tech cycle subsides, so should criticism regarding the UK deficiencies.

[ad_2]

Source link