[ad_1]

Just how much of an error was the government’s Help to Buy equity loan scheme? To its supporters, it has been a vital tool to get young homebuyers on the ladder. But to its detractors, and there are many, it has driven up property prices and boosted the profits of the nation’s biggest housebuilders — all while littering the country with unattractive, often shoddily built, new homes.

Today, nearly a year after the original equity loan scheme was withdrawn, and a year before the latest version is due to end, it seems like an opportune moment to pick over the bones of the policy, which some fear the market has grown dependent on.

Introduced in 2013, the equity loan scheme — one of a number of government initiatives badged under “Help to Buy” — provided buyers with a loan of 20 per cent of the purchase price of a new-build home. It has regularly been blamed for boosting house price inflation, most recently in a report from the House of Lords published in January. Some £29bn of taxpayers’ money will be spent on the scheme before it ends next year — the report said the money could be better spent on building more homes instead of tied up in equity loans

In fact, the report’s underlying research only found that Help to Buy had an effect on prices around the edge of London, not across the country. This isn’t surprising given two considerations: firstly, housebuilders are price takers — the price they sell their homes at is driven by the price of existing homes in the local area. And secondly, the scheme originally corrected a market failure: it bridged the affordability gap between buyers, the cost of new-build homes, and mortgage lenders who, since the financial crisis, had been reluctant to lend at loan-to-value ratios higher than 75 per cent on new-build properties. Rather than boosting the market, it simply put mortgage lending for new-builds on an equal footing with existing properties.

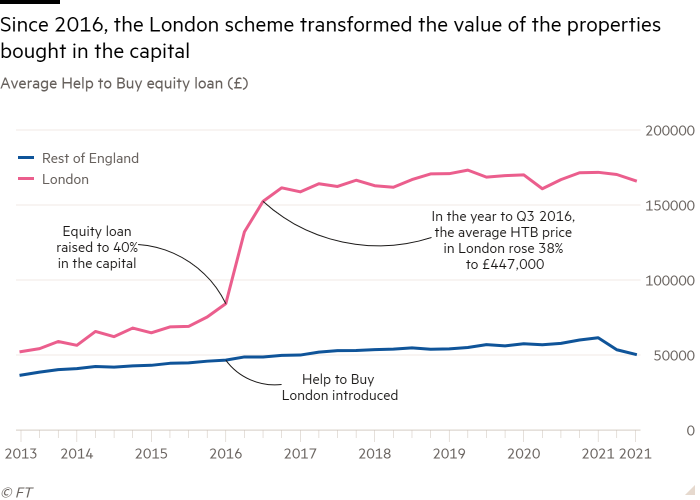

But in London, it’s a different story. Introduced in 2016, the London specific scheme increased the equity loan to 40 per cent of the property value. And prices raced: the average equity loan taken out in the capital jumped from £69,000 in Q3 2015 to £152,000 in Q3 2016. Any prospective first-time buyers considering a new-build home suddenly found themselves in a far better buying position if the home was just inside London than outside — creating the geographic divergence picked up in the research. As a result, the median house price paid under Help to Buy in London rose from £323,000 in Q3 2015 to £447,000 in Q3 2016.

While it’s unclear whether the equity loan scheme inflated prices nationally, it certainly coincided with the return of higher price growth after the credit crunch. If anything can be said to have turned the housing market around in 2013, though, it was another Help to Buy initiative, the mortgage guarantee policy. This persuaded lenders to return to higher volume, riskier lending in the wider housing market, until it was withdrawn in 2016. The equity loan scheme simply enabled new-build developers to piggyback on the wider recovery — and their piggy banks benefited.

Since 2013, developers have managed to capture most of the uplift in house prices in profit. Back then, for every new home the company built, Persimmon, one of the UK’s biggest builders, spent £144,400 on land and build costs and made a gross profit of £36,500, financial records show. By 2019, the land and build cost was unchanged, but the gross profit had nearly doubled to £71,300.

Last year, the equity loan scheme was changed so that it only applied to first-time buyers and it was subject to regional price caps. The latter has already led to some significant changes in the type, price, and location of Help to Buy homes.

The caps are most binding in the Midlands and the north, where they are below the average Help to Buy price recorded at the end of the old scheme. By Q3 2021, the first quarter completely under the new rules, average prices were already falling sharply. In the north-east, the average dropped 31 per cent, double the fall in the south-east. These price drops reflect the fact that the mix of homes being sold is changing. In Q1 2021, more than a third of homes sold through Help to Buy were detached homes, by Q3 that had fallen to just 14 per cent.

The changes also appear to be affecting supply. Research carried out by me and some colleagues found that, in Q3 2021, the number of new homes being built in areas where the cap was higher than the average price was 15 per cent down on the same quarter in 2019; in areas where the cap was lower, it dropped 46 per cent.

But what happens when the new scheme ends next year? Our analysis comparing private new-build completions and wider market transactions suggests that the majority of Help to Buy properties have been built in excess of what the market might have otherwise delivered.

Estate agency Savills estimates that the end of the equity loan could lead to a shortfall of 17,000 new homes per year compared with recent levels. Even that figure may be too low as it relies on the expansion of the housebuilders’ Deposit Unlock scheme — an insurance-based replacement for Help to Buy from the private sector.

The future of Help to Buy may also be affected by the government’s levelling up agenda. Spending on the scheme is disproportionately concentrated in London and the south. The latest annual cost of the equity loans — up to Q3 last year — was higher in London than the total spent in Yorkshire and Humber since the scheme began. Higher house prices in the south-east — which require larger equity loans — mean the scheme has been most active in areas with the most stretched affordability. But these are not the areas most in need of levelling up. Whether the equity loan survives past its current end date next March will depend on the government’s policy priorities.

As for the hundreds of thousands of buyers who have used Help to Buy, the situation is far from clear. Data from Homes England, which manages the scheme, shows a profit on the equity loans that have been repaid. This suggests the majority of those repaying have seen the value of their home rise. But this doesn’t account for those who haven’t sold or can’t sell. The longer-term success or failure of the equity loan cannot be determined in insolation. It will also depend on resolving the cladding crisis, the leasehold crisis, and the building quality crisis, all while the resale value of newbuilds — particularly flats — looks uncertain following the pandemic and in the face of the growing living costs.

Neal Hudson is a housing market analyst and founder of the consultancy BuiltPlace

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first

[ad_2]

Source link