[ad_1]

Europe’s fragmented single market is like an obstacle course, relegating the region’s companies to also-rans in the global race for growth.

The failure to harmonise the rules inside the trading bloc has allowed US companies to take the lead in the growth stakes, say some of the continent’s leading industrialists. A patchwork of regulations is stifling innovation and expansion, they believe.

“There are so many obstacles and barriers that are making it hard to grow,” said Carl-Henric Svanberg, chair of the influential Brussels-based European Round Table for Industry, which brings together leaders of 60 of the continent’s biggest industrial and technology companies.

He said the US economy grew far more strongly than Europe in the decade between 2008 and 2018. US cumulative real growth was close to 19 per cent, against 11.4 per cent for the EU, including the UK. “The price we pay for not realising that growth is huge,” added Svanberg, who is also chair of Sweden’s AB Volvo and has led European giants such as Ericsson and BP.

Svanberg’s comments in an interview with the Financial Times come as Europe shares out a €750bn post-Covid-19 recovery fund aimed at driving the EU’s digital and green transition. But business leaders fret that failure to fully harmonise rules in areas such as digital services, capital markets and energy is holding back European companies.

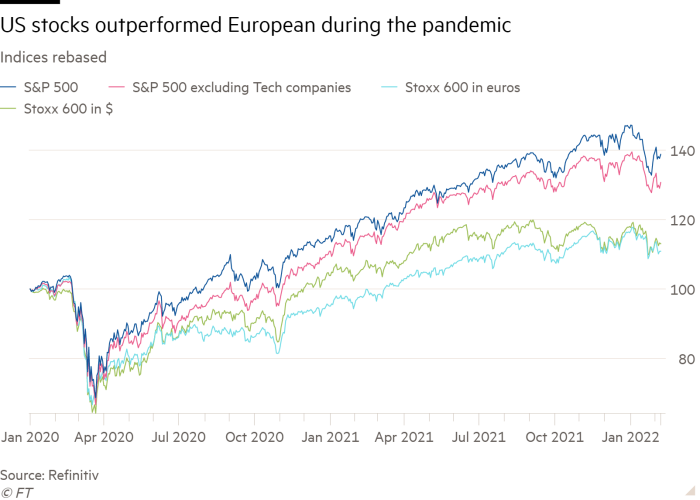

The region’s problems appear to have been exacerbated during the pandemic, when just 16 European companies, including four from the UK and Switzerland, edged into the global top 100 in terms of market capitalisation growth over the two years to the end of 2021.

In contrast, the US delivered 58. During the same period, the S&P 500 rose by 46 per cent, against just a 16 per cent rise for Europe’s Stoxx 600. The gap remains, even though in 2022 investors are retreating from the tech stocks that drove US valuations.

“We are very slow, very complicated,” said Martin Brudermüller, chief executive of European chemicals group BASF. “Low-carbon solutions and digitally advanced technologies can be scaled up much quicker by companies if they are not facing national barriers, lengthy permitting procedures and fragmented policies in various member states.”

European companies have long lagged behind rivals in the US, where companies are able to scale up more quickly because of a single market of 330m people sharing the same language, harmonised regulations and deeper capital markets.

Analysis by capital markets think-tank, New Financial, found that, on average, capital markets across the EU27 are half as large relative to gross domestic product as in the UK, which in turn is roughly half as developed as the US.

But Andre Köttner, global co-head of equities at Germany’s DWS, said Europe suffered a double blow from the pandemic. First, it lacks fast-growing global tech giants. Companies such as Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google were able to exploit the shift to online consumption that came with the global lockdown.

Second, “Europe treated the Covid pandemic more severely than other countries, so companies were hit harder,” Köttner said. “In the US, there were fewer restrictions.”

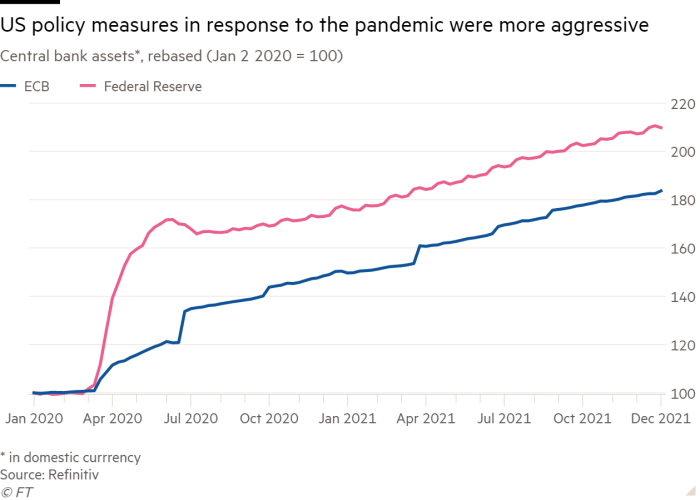

There was also a difference in the speed and scale of government support, according to Jorma Ollila, the former chair of both Royal Dutch Shell and Nokia, and now a board member at investment bank Perella Weinberg Partners. “Expansionary fiscal and monetary policies had an impact in Europe, but the impact in the US was bigger,” he said. US measures were “more aggressive than in Europe. And the US started earlier.”

The difference is highlighted by the substantially greater expansion of the US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet compared with the European central bank in the early months of the pandemic. By the end of March 2020, Donald Trump, then US president, had signed into law a bill outlining $2.3tn in emergency measures to aid individuals, businesses and the wider economy, equal to roughly 11 per cent of GDP.

European support was also structured in a way that did not favour competitiveness, said Simon Freakley, chief executive of consultancy AlixPartners in New York. “In the US, federal programmes supported the employee directly while in Europe they supported the employer, to protect employment in Europe,” he said.

“There was no incentive for employers to slim down workforces. So US companies have come out of the blocks quicker than in Europe.”

Data from Refinitiv confirms that view, with aggregated earnings in the S&P 500 surpassing early 2019 levels by the third quarter of 2020, while Europe’s Stoxx 600 companies took until the first quarter of last year to recover.

But the pandemic experience does not mean that European companies are worse than their American rivals, insisted Drew Dickson, chief investment officer of London-based fund, Albert Bridge Capital.

Nor does Europe’s lack of big global tech companies signal something rotten in the state of European business. Instead, that is simply “the outcome of history and chance” — the migration decades ago of tech geeks to Silicon Valley. “It wasn’t Chicago, New York, Nashville or Austin,” he said.

“It isn’t an American thing. You have four of the biggest companies in the world within 40 miles of each other. There was a clustering that happened.”

European companies are highly competitive in other sectors, Dickson argued. “If there is a Boeing, there is an Airbus,” he said. “Where there is a GM, there is Volkswagen. A Southwest, a Ryanair. Once you are in other sectors there is no clear winner. This argument that somehow there is something better in the US is wrong, except in tech.”

Daniel Grosvenor, director of equity strategy at Oxford Economics, agreed that there is a danger of being too pessimistic about European companies. “They haven’t done badly in absolute terms. European profit margins are back at an all-time high. It is not that they had a bad pandemic, just that they underperformed their US counterparts.”

Dickson argued that the underperformance has been driven in part by global investors’ obsession with the high-growth tech stocks that dominate US indices. Europe, meanwhile, is weighted towards value stocks, or companies where profits or book values suggest that a higher share price is merited.

But Europe’s lack of global tech giants is still a weakness in an increasingly connected world, said James Watson, director of economics at the lobby group BusinessEurope. “The concern is we are not in the areas where we expect profits to be in the future,” he said.

There are signs that this may be changing. Last year, Europe’s tech sector drew investment of $100bn, close to three times the level recorded in 2020. According to Atomico’s State of European Tech 2021 report, the sector added $1tn in value over just eight months for a total of $3tn last year, and returns on venture capital investment in Europe are outpacing the US. But there is still a big gap.

So the question is whether the pace can be accelerated as European governments prepare to spend roughly a third of the €750bn recovery fund on digital transformation.

For Svanberg that can only happen if barriers to the single market are addressed. For example, “we don’t have a single market for 5G in Europe,” he said. “That makes it harder for digital companies to scale. And we have to have digital success, otherwise we won’t be able to deliver on the green transformation.”

It is not just big companies that worry about the scope for growth if Europe fails to create a comprehensive single market. “A lot of small and medium-sized businesses still don’t consider Europe as a domestic market,” said Ben Butters, chief executive of Eurochambres, which represents more than 20m businesses, most of which are SMEs.

“There are many barriers that preclude business from capitalising on the single market. When that happens, hopefully we will have a lot more names on that list of leaders.”

[ad_2]

Source link