[ad_1]

Just a few months ago, financial markets were in the midst of one of the wildest anything-goes phases in history. Today, the mood is very different.

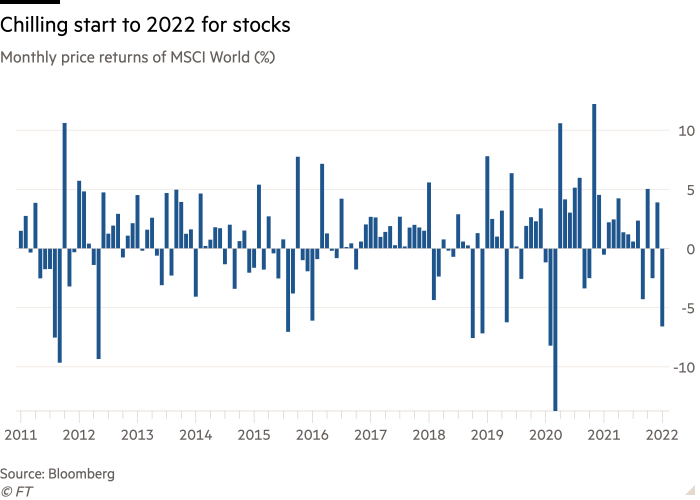

Despite a powerful rebound in the last days of January, the MSCI World benchmark of global stocks fell by more than 6 per cent last month, making this the worst start to a year since 2008. That is a loss of value of roughly $6tn.

US technology shares that dominated the post-financial crisis rally this week extended their fall in 2022 to almost 10 per cent, after Facebook shocked investors with poor results.

The pain has been even more profound in many of the more speculative corners of markets, and supposed safer havens have failed to provide much succour. Cryptocurrencies shed almost half their value. Even bonds — which are supposed to buttress investors against such spurts of turbulence — have lost money this year. Only nine of the 38 major asset classes tracked by Deutsche Bank ended January in positive territory.

“The intraday swings have been breathtaking and some key segments are now in a bear market,” says Jim Paulsen, chief investment strategist at The Leuthold Group, an independent investment research firm. “Who knows how long the carnage associated with this rollercoaster ride will continue and where the stock market will ultimately bottom?”

The primary cause of the market angst is obvious: After nearly two years of aggressive stimulus to soften the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, many central banks have felt compelled by accelerating inflation to abruptly tighten their policies. Multi-trillion dollar bond-buying programmes are being wound down, and interest rate increases are coming. The Bank of England became the first major central bank to lift rates in December, and followed with a second increase this week. It is expected to be joined by a host of others in the coming months: even the European Central Bank on Thursday hinted it may raise rates in 2022.

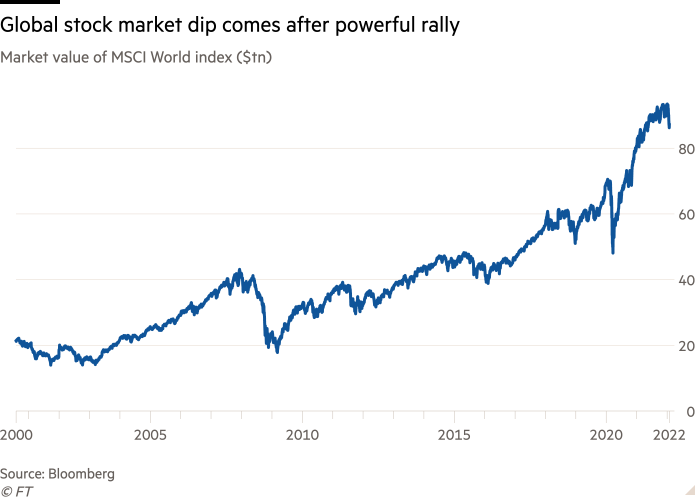

The fear is that this could mark an inflection point for markets. For over a decade, investors have learned that every wobble was merely an opportunity to buy, as central banks would always act swiftly to loosen monetary policy to forestall a serious crash. “Buy the dip” became a mantra, and ultimately even a meme. But now the hands of central banks have been tied by a spurt of inflation.

The Federal Reserve last month underscored how a very different market regime may now be beckoning On January 26, chair Jay Powell, undaunted by the recent bout of volatility, indicated that the US central bank was willing to raise interest rates more aggressively than previously hinted.

“This has been a significant correction,” says Kristina Hooper, chief global market strategist at the investment group Invesco. “Markets have been forced to realise that the Fed means to curtail inflation and has pivoted completely.”

At the same time, markets have to confront myriad other unsettling dangers, such as rising fears that Russia could invade Ukraine, slowing global growth, messy supply chains, China’s wilting property sector and the continuing battle with the coronavirus pandemic and its economic aftermath.

Is this just an overdue bout of turbulence — perhaps even an opportunity to buy some unfairly banged-up assets — or the end of a market era and the dawn of a new, less generous one? And how should retail investors tackle twists and turns that are discombobulating even experienced, professional money managers?

The ‘Spec Tec’ wreck

Star US fund manager Cathie Wood was unbowed at her investment firm’s annual “Big Ideas” summit last month, after her flagship fund — the Ark Disruptive Innovation ETF — suffered a brutal sell-off in recent weeks.

“Volatility is not always a bad thing,” she insisted to the thousands of Ark investors who watched the livestream. “I have never seen innovation on sale the way it is today.”

Wood became emblematic of the bull run that started in late March 2020, when central banks started spraying money at markets to prevent the economic disaster caused by Covid-induced lockdowns from escalating into a financial crisis. Through a series of actively-managed exchange traded funds, Wood’s Florida-based Ark Invest made huge bets on disruptive technologies ranging from electric cars to cryptocurrencies.

Wood became a phenomenon, attracting hordes of ordinary investors who were convinced by her vision. At its peak in early 2021, Ark Invest’s line-up of ETFs managed $61bn and boasted records that would be the envy of any hedge fund titan. To many, the transparency of her trades and research was a breath of fresh air. Then it all unravelled.

The Ark Disruptive Innovation ETF has now lost about 55 per cent since the February 2021 peak. It is a stunning reversal for Ark and, more broadly, the speculative technology trades that she made her hallmark. Goldman Sachs’s index of unprofitable, often early-stage tech stocks quintupled between the beginning of 2020 and a February 2021 peak, but has halved in value since.

In some cases, analysts say Ark’s investor inflows were clearly the main driver of the performance of its stocks and, as the tide turned, Ark being forced to sell was the primary cause of their subsequent pummeling. For the rest, it comes down to how investors value so-called “growth stocks” whose most profitable days are likely in the future.

In a world where growth in many traditional industries is scarce, investors are usually willing to pay more for shares of companies that are still growing quickly. Bond yields are also an important input into popular financial valuation models; if they are low it increases the value of future profits.

But now that the economy is booming, inflation accelerating and bond yields rising, growth stocks tend to be hit.

This made it easy for many investors initially to shrug off last year’s quivers as an overdue and healthy clean-out of the excessive boom in “speculative technology” that struck markets in 2020-21. In addition to “spec tech” stocks, so-called “special purpose acquisition vehicles” (SPACs) — blank-cheque companies that boomed in the mania — and “meme stocks” such as AMC and GameStop also slid late last year and in early 2022.

Despite chunks of the stock market falling into bear markets last year, the headline indices mostly climbed higher, thanks to benchmark heavyweights such as Microsoft or Google largely shrugging off the Federal Reserve’s hawkish shift in December. Apple even became the first $3tn company on the planet at the start of January.

However, their resilience then began to fade, as investors increasingly started to fret over how serious central banks now appear to be about raising interest rates. Of the 10 most valuable companies in the world, only Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, Saudi Aramco, the oil company, Alphabet and Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway have managed to eke out gains this year.

Most notably, Facebook’s parent Meta lost a stunning $200bn in market capitalisation after reporting disappointing results on Wednesday — the single biggest one-day bout of value destruction in corporate history. Coupled with negative surprises from PayPal and Spotify, two other tech darlings, it caused a new shiver of investor fear which reversed the Nasdaq’s recent recovery.

“We are now in an interest rate hiking cycle and that means headwinds for markets, especially equity markets,” warns Michael Strobaek, global chief investment officer at Credit Suisse. “The market environment now is no longer the ‘buy the dip’ environment that was in place when the Fed was all in.”

Jeremy Grantham, the famed investor who has long rung the alarm about what he calls the fourth “superbubble” of the past 100 years, recently warned that the downturn in more speculative stocks may only have been a harbinger of a far broader, more painful crash that could now come at any moment.

“At the end of the great bubbles it seems as if the confidence termites attack the most speculative and vulnerable first and work their way up, sometimes quite slowly, to the blue-chips,” he wrote in a report late last month. “This checklist for a superbubble running through its phases is now complete and the wild rumpus can begin at any time.”

However, Grantham has a well-earned reputation for often extreme bearishness, and has warned of imminent stock market calamities for much of the past decade. He might be right this time, but many investors remain fairly relaxed. They see the recent spurt of volatility as a natural reaction to central banks changing direction. With markets now reflecting this, the sell-off has faded and prices have even begun to edge higher again.

“The more we look at equity market internals and positioning, the more convinced we are that market participants have substantially adjusted to the reality of higher inflation and a higher yield environment,” Kevin Russell, the chief investment officer of UBS O’Connor, the Swiss bank’s hedge fund, said in a letter to investors last month.

Nor is it just Ark Invest’s Wood who now reckons that many good investments are available. Hedge fund manager Bill Ackman revealed that he had cashed in a $1.25bn profit from betting on interest rate rises and ploughed the proceeds into Netflix after the streaming company reported poor quarterly results last month.

“Many of our best investments have emerged when other investors, whose time horizons are short term, discard great companies at prices that look extraordinarily attractive when one has a long-term horizon,” Ackman said in his letter to investors announcing his wager.

It may be hard to remember in the midst of a sell-off — and especially after the long bull run that started after the 2009 financial crisis — but stock market corrections are fairly normal. As long as the economy doesn’t enter a recession, they tend to be opportunities, analysts say.

Goldman Sachs has crunched the numbers for US bourses, and estimates that there have been 21 non-recession corrections since 1950, where stocks fell by an average of 15 per cent peak-to-trough without the national economy contracting. Buying US stocks whenever they fell 10 per cent from their peak, regardless of whether that was the trough or not, has generated median returns of 15 per cent over the next 12 months.

“As markets continue to digest the outlook for the Fed, rates and growth, we believe that the recent equity drawdown will prove to be a correction in a longer bull market cycle, rather than the start of a new bear market, and see remaining downside risk as limited so long as economies continue to grow,” Allison Nathan, a senior Goldman Sachs strategist, said in a report.

Time in the market

For now, this remains the prevalent view among analysts and investors. Invesco’s Hooper compares the recent bout of investor angst over central banks to when her children were young and worried over monsters lurking under the bed. In the morning they’d realise that the fangs and horns they saw in the dark were nothing more than a few dirty socks. She suspects this will also prove the case with central banks, with the reality of a few interest rate increases proving less scary than the prospect.

“This volatility is likely to be temporary and it’s natural that it happens at the start of the monetary tightening cycle,” she argues. “If you have a long enough time horizon these things are buying opportunities.”

Ed Yardeni, a veteran financial analyst, points out that real bear markets — typically defined as a 20 per cent drop from the peak — are almost only caused by economic recessions. He struggles to see how one could happen just because the Federal Reserve might raise interest rates to 2 per cent by 2023. Other central banks — even hawkish ones like the Bank of England and Bank of Canada — are unlikely to be able to move much further than the Fed, and the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan are unlikely to go nearly as far.

Notably, some areas of the global stock market have been fine this year. The recent sell-off has mostly been concentrated in more expensive stocks — those trading at high multiples of their profits or revenues. Meanwhile, many so-called “value” stocks, or markets largely shunned in the great 2020-21 boom, have either been resilient or enjoyed extended rallies.

For example, anything expected to benefit from a more inflationary environment and higher interest rates has still done well. Global bank stocks have mostly shrugged off the recent turbulence and risen almost 5 per cent this year, while energy stocks have climbed 15 per cent after 35 per cent returns in 2021. Bloomberg’s natural resources index has risen 10 per cent already this year. Brazilian equities, some of the world’s worst performers over the past decade, have started 2022 with an 13 per cent jump.

The long-suffering UK equity market has held on to last year’s gains, thanks to its mix of beaten-up value stocks finally regaining some investor favour, and some expect a renaissance in the coming year. JPMorgan analysts have been gloomy about UK stocks for six years, but now expect a “better showing” in 2022 thanks to the market’s “very attractive” valuations.

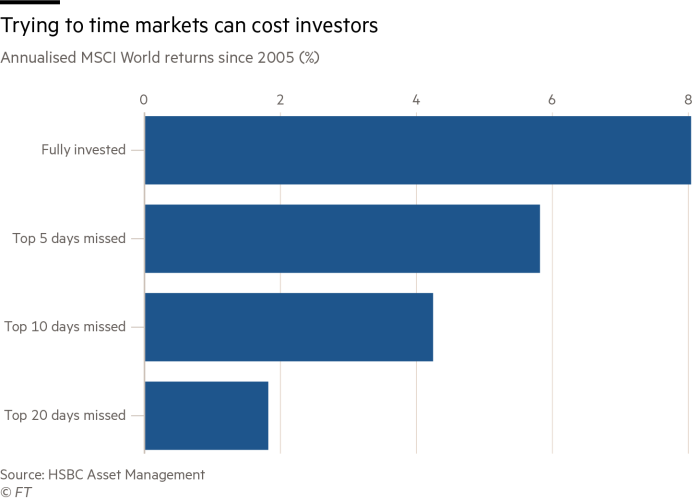

Fortunately, how to respond to the recent turbulence is not a problem that should trouble most retail investors. The expensive lesson that markets keep teaching us but most keep forgetting is that flitting in and out in response to rallies and routs is usually foolish.

Stuart Kirk, head of research at HSBC Asset Management, points out that investors often dump stocks after big sell-offs, but then miss out on the big rebounds that often follow. Simply missing out on the top 10 days of equity bounces would on average halve an investor’s annual returns, he estimates.

As Vanguard’s erstwhile founder Jack Bogle pithily put it, it’s about time in the market, rather than timing the market. It is always better to take a dull but prudent approach by investing steadily in a diversified range of cheap, broadly-invested funds and block out the market noise. And if an investor is tempted to dip in, they should stay the course.

“When you buy something on sale in retail you usually feel good about it. If you buy something on sale in markets, then you often feel queasy,” Hooper notes. “But there are a lot of positives. Investors need to look at the big picture.”

[ad_2]

Source link