[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday

Hello.

It’s a year into President Joe Biden’s administration. How’s he doing? Well, it probably doesn’t matter much for the voters, for whom inflation, growth and the pandemic are more important, but from the trade point of view he’s definitely towards the interventionist side, slightly moderated by expediency.

Biden has kept those parts of the Trump inheritance he feels are politically vital (China tariffs), jury-rigged some makeshift solutions to those he doesn’t (Airbus-Boeing, Section 232 tariffs) and, most worryingly, set in motion a bunch of processes (Buy American, electric vehicle domestic-content tax reliefs, supply chain resilience) which could — repeat could — end up in some serious protectionism. And he has stayed out of the CPTPP and done little except grandstand in the World Trade Organization. Well, he did say trade wasn’t going to be a priority.

Today’s main piece is on an issue where Biden has continued Trump’s wrong-headed policy and it still isn’t working, the “phase 1” deal with China. Charted waters assesses how 3D printing and “reshoring” have offered only limited protection to supply chains.

We want to hear from you. Send any thoughts to trade.secrets@ft.com or email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

Biden’s futile persistence with Trump’s China deal

Time was when China recording a record trade surplus would have thrown all of Washington into a tizzy: stern words of disapproval from the Treasury, cries of woe from rustbelt congressmen, rousing calls for currency market counter-intervention from the more hotheaded think-tankers, that kind of thing.

Well, China did precisely that 10 days ago and while no one was exactly delighted, it’s not the biggest thing to have happened in US politics so far this year. I’m not going to speculate on exactly why Washington reacts to events any more than I can predict what our toddler is going to do when told it’s bedtime. But it’s worth noting that, while the US analysis of its deficit continues to be wrong-headed, at least it’s not using trade and current account deficits as the main reason to further ramp up its trade war.

Current account balances are one of those things where it’s best to call in the macroeconomists, who correctly look at the savings-investment relationship inside a country rather than at external trade policy. You can argue that China ran surpluses for years because the government subsidised and promoted exports while discouraging imports with dense thickets of regulation, but so did India, which has had structural deficits for decades.

Sure, Chinese sales abroad received a boost in 2020 and 2021 from being a big manufacturing exporter — all that PPE and all those consumer durables. It turns out that, despite all the stories about Chinese factories being closed and ports ceasing to function, China’s harsh lockdowns affected its domestic services consumption more than they did goods exports.

If the pandemic eases, the IMF reckons that global imbalances, which widened in 2020 and probably in 2021, are going to shrink over the next few years. And as the great Michael Pettis points out (in the FT, of course), the current account deficit reflects a much more longstanding and more worrying trend of China failing to shift growth to households in the form of higher wages and thus to domestic consumption. The trade surplus is the symptom of something wrong at home — the wider thesis is explored in the excellent Trade Wars Are Class Wars by Pettis and Matthew Klein. If we’re interested in global imbalances we need to keep watching Chinese domestic policy and outcomes more than anything else.

Obviously, that’s not going to stop US trade policy having a go at closing deficits, futile though its efforts might be. One good thing is that the US is no longer possessed of the notion that currencies are the big issue. There was a perfectly reasonable thesis that Chinese intervention to hold down the renminbi had at least contributed somewhat to its surpluses in the 2000s. But Trump continued to have an intermittent obsession with Chinese currency manipulation despite the fact that by the time he came on the scene Beijing was propping up the renminbi more than holding it down. The IMF thinks the Chinese real exchange rate is just about fairly valued, as far as it can tell.

However, Trump simply switched from an outdated currency solution to a wrong-headed trade one. He slammed tariffs on imports from China and signed the phase 1 deal that was supposed to reduce the bilateral deficit via direct purchases of US exports, famously including soyabeans. In lieu of any other good ideas, the Biden administration has continued to try to hold Beijing to its obligations. As we’ve noted several times, they remain well short of target.

Either way, even ignoring the issue of domestic imbalances, phase 1 clearly isn’t a solution for China’s overall current account situation. It will just shift the surplus elsewhere, and as such is far more pointless than the currency flexibility campaigns of the 2000s. True, the bilateral US-China imbalance shrank during 2020 and 2021, but misreporting almost certainly heavily overstated that move.

In theory, the other bits of the phase 1 deal, which involve access for US companies to the Chinese economy in a variety of sectors, might help the process of transitioning a little bit if they loosen up services markets for domestic consumers. But even assuming that gets implemented, the main levers of change remain with the Chinese authorities. There isn’t a whole lot that trade or even international macro policy can do about this. And despite some clamping down on excesses of corporate overinvestment such as Evergrande, China is some way away from correcting the internal imbalances that feed the external ones.

Trade policy can’t really fix current account deficits. It’s annoying to trade policymakers, but there it is. And pretending it can, as the phase 1 deal does, only creates unrealistic expectations and draws attention away from the real problems.

Charted waters

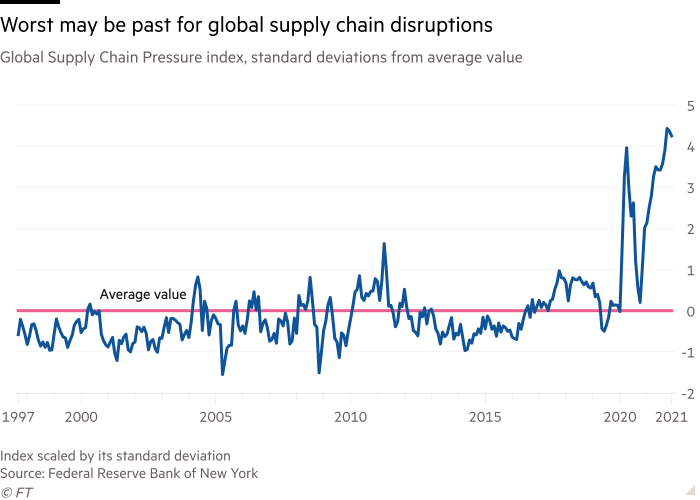

High-profile disruptions to global supply chains — including the temporary blockage of the Suez Canal, floods and fires in Texas and Japan, as well as ongoing semiconductor production bottlenecks — sparked predictions of mass retrenching of production closer to home markets and use of technologies such as 3D printing to make hard-to-source components.

Last year, a study by Lux Research estimated that the market for 3D printed parts, which was worth $12bn in 2020, would grow to more than $50bn by the end of the decade.

However, the recovery in the global supply chain market has provided evidence that such activity is likely to be at best a niche activity as the efficiencies of international trade trump efforts to manufacture at home.

A survey of European companies conducted by EY in the early spring lockdowns of 2020 found that more than four-fifths were considering bringing their supply chains closer to home. When the same survey was conducted in April last year, however, that view was shared by just 20 per cent of respondents.

Trade links

The US is in talks with Qatar and other countries to supply gas to Europe in case of a Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The EU continues to move slowly towards creating a legal “due diligence” requirement for companies to stamp out human rights and environmental standards violations in their supply chains — we’ve written about this several times.

China has appointed its first special political envoy to the Horn of Africa, signalling a more active diplomatic effort to protect its investments from conflict in the region.

France wants to make agricultural imports adhere to the same production standards that EU farmers have to follow. This promises a raft of WTO litigation if it gets through — we wrote about the idea here.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen wants Europe to double its share of semiconductor production to 20 per cent by 2030.

[ad_2]

Source link