[ad_1]

This article is an on-site version of our Britain after Brexit newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every week

Good afternoon. The Britain after Brexit briefing is back for 2022, the year that Brexit may finally really “get done” — or at least the first phase of Brexit.

If all goes to plan, this will come in two parts: firstly an agreement in the next two or three months to put the post-Brexit trade rules for Northern Ireland on a politically and economically sustainable footing; secondly the phasing in of full border controls on imported goods from the EU into the UK, of which more in subsequent editions.

On the Northern Ireland trade question, after a Christmas and New Year break where I understand officials really did take time off, talks to try and cut a deal with Brussels will begin in earnest in the UK next week. The Irish foreign minister Simon Coveney is also in London tonight in order to lay some of the groundwork.

In pondering the challenges of the coming negotiation, it’s worth recalling at the outset that the EU and the UK do already have an agreement which was negotiated in 2019 — the benighted Northern Ireland Protocol. It’s just that the UK government, in retrospect, has declared it to be unsustainable.

The original agreement remains the baseline from which the EU measures its concessions and that is likely to be a fundamental source of tension between the two sides as they try to thrash out a compromise.

Following the resignation of Lord David Frost, it is now Liz Truss, the foreign secretary, who will negotiate with the EU Brexit commissioner Maros Sefcovic. But while Truss might lighten the tone with her trademark goofy optimism, it doesn’t change the fundamental problems.

This remains the fact that Boris Johnson’s decision to leave Northern Ireland in the EU’s single market for goods — necessitating EU-style border checks on goods going from Great Britain to the region — has been honoured in the breach since it came into force in 2020.

The deal has never been fully implemented, initially because the EU and the UK agreed ‘grace periods’ to give business time to adapt, but subsequently because the UK has extended those grace periods, first unilaterally and latterly with the grudging connivance of Brussels.

The difficulty is that the UK baseline for success is to further reduce that already partially-implemented Irish Sea border, while the EU side still seeks to defend the basic concept of the protocol, which requires goods to conform to EU rules.

So while some momentum was built up towards a deal before Christmas by Frost’s decision to soften his demands to remove the European Court of Justice and an acknowledgment that certain controls at the Irish Sea border would be required, the two sides remain some way apart.

In October the EU put forward ideas to smooth the border, which Sefcovic claimed will reduce customs checks by 50 per cent and so-called “SPS” checks on plant and animal products by 80 per cent. However, those are not figures that the UK or Northern Ireland industry recognise on the ground.

One reason is that the EU might argue that it is reducing SPS checks by “80 per cent” from the original deal — which required the full implementation of export health certificates (for goods going from Dover to Calais) that have never been required.

Some EU officials talk about reducing the “intensity” of checks, rather than the “quantum”. So the number of lines in a customs form might shrink by 50 per cent, but you still need the form.

That’s fine, but it is the practical impacts, rather than semantic niceties, that will preoccupy Truss as she tries to reach a deal she can sell to restless backbenchers and even, with luck, more moderate Unionists in Northern Ireland.

One key bone of contention cited by officials and trade groups is the EU’s offer to create an “express lane” for goods that can be proven to be destined only for consumption in Northern Ireland — but limited only to “primary products originating in the UK”.

In practice, say trade groups, that means a GB-based food manufacturer that uses, say, Brazilian beef in a ready meal, must ‘export’ the product into Northern Ireland either via the continental EU or through Dublin. This, they say, is impractical.

The EU — recalling the original deal — argues that such a restriction is fundamental to the protocol, and necessary to prevent Northern Ireland becoming a backdoor for non-UK products into the EU single market. It also argues that there is plenty of meat in the single market that can be made into pies for Northern Ireland.

Ultimately, this was the deal that Johnson signed, but expect a full-court press from Northern Irish trade groups and the UK this month to try to make the EU side understand the challenges this approach throws up for NI supply chains and the impact it will have on consumer choices and politics in the region.

Gaps also remain for goods going in the other direction — from Northern Ireland into Great Britain — where the UK government has promised “unfettered access” for NI businesses to the UK internal market.

The difficulty is that under EU rules, goods leaving the EU single market should submit exit declarations. Mindful of the political symbolism of this, the EU agreed in the 2019 deal that this procedure was not necessary for Northern Ireland goods being sent into Great Britain, accepting instead that data from shipping manifests could act as a substitute.

But, in its demands to reform the protocol last July, the UK government said the system was “not operable without putting in place burdensome new requirements to collect further information” and requested a new settlement “to definitively eliminate these requirements”.

The EU did not address the issue in its suggested package of changes last October, so as things stand, Brussels continues to cling to the original deal. Fixing this will be another key part of negotiations.

Resolving gaps on these kinds of issues are core to a workable deal. The UK has accepted that shipping goods from Birmingham to Belfast cannot be exactly the same as sending them from Birmingham to Brighton. The question is how different does it really need to be?

With Northern Ireland elections looming in May, the pressure is on to do a deal, not least because the UK government is facing a series of other headwinds — inflation, labour shortages, supply chain issue, rising energy prices — that mean a sizeable chunk of the Cabinet want the Northern Ireland issue put to bed.

And Truss, as foreign secretary with one eye on the top job, arguably has a broader appreciation of the UK’s strategic priorities than Frost, while the EU side also points towards the logic of doing a deal.

But all politics is ultimately local. Any deal Truss strikes will crystallise a trade border in the Irish Sea that Johnson has always been in denial over. And to sell that back home, Truss will need wins that measure up against the UK’s benchmarks, not the EU’s.

Do you work in an industry that has been affected by the UK’s departure from the EU single market and customs union? If so, how is the change hurting — or even benefiting — you and your business? Please keep your feedback coming to brexitbrief@ft.com.

Brexit in numbers

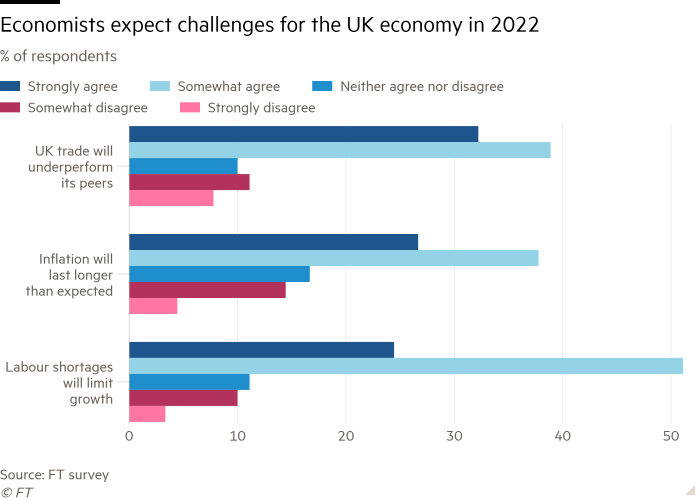

Looming over the negotiation is, of course, a deteriorating economic climate which the FT’s annual survey of economists reckons will be exacerbated by Brexit.

This is not as simple as pure trade friction, but a combination of added bureaucracy that reduces imports and exports; a less flexible labour market caused by ending free movement; and a less optimistic climate for investment, impeded in part by the fact that the UK is no longer an easy gateway into the EU single market.

In the opinion of Paul de Grauwe, professor at the London School of Economics: “Recoveries are driven by optimism about the future . . . Brexit will impose chronic pessimism about the future of the UK economy.”

Already business sentiment seems grim. According to December PMI survey data the UK was the only western economy to see falling exports — and a quarter of UK manufacturers cited Brexit as the reason for the fall.

And, finally, three unmissable Brexit stories

One year on, as far as Northern Ireland is concerned, Brexit is nowhere near done, writes Jude Webber from Belfast. As she points out in this excellent piece, the UK region is in a significant election year, with polls showing unionist parties on course to lose their majority for the first time — and among the most pivotal issues in the May 5 elections is Northern Ireland’s post-Brexit trading arrangements.

The Tories are wondering what happened to the Brexit they promised, says Robert Shrimsley in his latest column. As he writes: “With personal and corporate tax rises just introduced, ministers pledging not to scale back employment rights and an increasing role for the state, the buccaneering post-Brexit vision of a low-tax, low-regulation UK seems more remote than ever. So long Singapore-on-Thames, hello Sweden.”

The government is overhauling England’s agricultural subsidies after Brexit and, over the next two decades, planning to restore land almost twice the area of London to nature. Initial projects will aim to restore 10,000 hectares of wildlife habitat and save carbon emissions equivalent to that of 25,000 cars, while improving the habitat of about half of England’s most threatened species. Find out what they are, and more about the new plans.

[ad_2]

Source link