[ad_1]

US index-tracking funds are throwing away $3.9bn a year by using predictable, mechanical trading strategies that are exploited by nimbler market participants, according to academic research.

The losses would cost an investor who built up a $2m retirement portfolio over 30 years via passive mutual or exchange traded funds $29,000, the analysis found.

“The trading cost of mechanical rebalancing is large in many senses. It is comparable to total management fees charged by ETF managers,” said Sida Li, a PhD student at the University of Illinois and author of the paper.

The research centred on the regular rebalancing, typically quarterly, performed by passive ETFs to ensure they remain aligned to the changing composition of their underlying index.

Due to the strict methodology of indices, traders know what the index changes are going to be before they are implemented. This gives them the opportunity to front-run the trades that they know rules-based ETFs must make, moving prices against these funds.

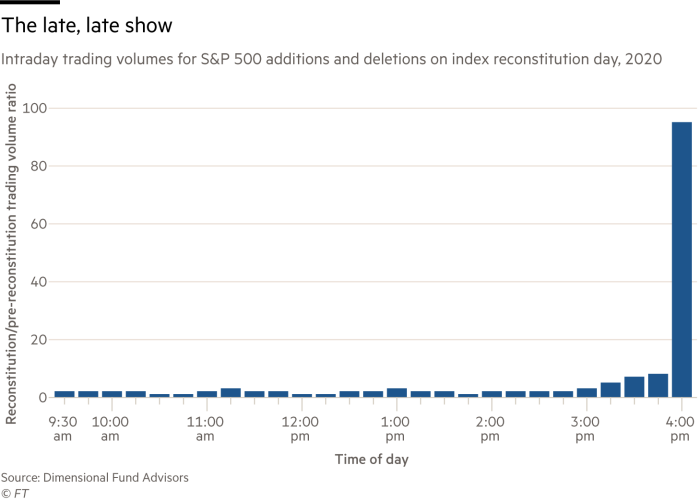

Li found that the majority of US-listed equity ETFs not only pre-announce their rebalances, but also transact at the 4pm closing prices on the stipulated index rebalancing days, in order to minimise tracking error.

The research also found that the price of the stocks ETFs buy on average rises by 67 basis points in the five trading days prior to the rebalance, only to fall 20bp over the subsequent 20 days.

Given that the median portfolio turnover rate for US equity ETFs was 16 per cent in 2020, this translates into an average annual 14.6bp performance hit.

Li, who described these transparent ETFs’ rebalancing strategies as “sunshine trading”, compared them to what he called “opaque ETFs”. These funds only reported their portfolios at the end of the month, rather than daily, as sunshine ETFs do.

However all ETFs report their net asset value on a daily basis, which allowed Li to compare 16 opaque ETFs that track identical indices to 16 sunshine ones.

The NAVs of these ETF pairs exhibited a correlation of 0.9999 outside index rebalancing windows, but only 0.97 during quarterly rebalancings, demonstrating that they were trading in a different manner.

Li found that the opaque ETFs conducted some trades before the designated rebalancing date and some afterwards. On average, by camouflaging when they traded they cut 34bp a trade off the execution shortfall suffered by sunshine ETFs, equivalent to an annual saving of 7.3bp a year across the portfolio as a whole.

The paper also looked at ETFs that are “self-indexed” against an in-house benchmark, such as the Schwab 1000 ETF (SCHK) that tracks the Schwab 1000 index, which has been permitted in the US since 2013.

These internal indices do not make it clear in advance which stocks will enter or leave an index at a rebalancing, reducing the ability for others to front-run them.

By camouflaging what they are trading, these self-indexing ETFs have rebalancing costs that are 30bp a trade below that of sunshine ETFs, Li found, equivalent to 9.6bp a year across the whole portfolio.

Ben Johnson, director of global ETF research at Morningstar, said there was “no arguing that index rebalancing and reconstitution trades impact share prices”.

However he believed the exact magnitude of the effect was “impossible to measure”.

“You cannot control for all the other myriad factors that may impact share prices at any moment in time to isolate the market impact of index trading,” Johnson said. “I’d say that these estimates are likely multiples higher than the actual impact.”

Wes Crill, head of investment strategists at Dimensional Fund Advisors, said: “We have done similar studies in the past. All of these points to there being a potential value added from having flexibility in when you make your trades.”

Long-running indices, such as the S&P 500, were not designed to be tracked by funds, and were originally merely market gauges. Nevertheless, Li argued that investors should have an understanding of probable transaction costs and the industry should try to optimise the impact of trading.

One way to do that is to track an index with a lower turnover rate, Li said. Last year these rates ranged from 5 per cent for the S&P 500 to 20 per cent for the Russell 2000 and 52 per cent for the S&P SmallCap 600 Growth index, according to the prospectuses of ETFs tracking them. For total market indices they can be as low as 3 to 4 per cent.

Another is to trade in a smarter way. Li pointed to CRSP, an index provider, whose indices rebalance in 20 per cent increments over five days, rather than in one go.

Eric Frait, a managing director at CRSP, said it had employed “transitional reconstitution” since 2017. “It’s never the case that everything turns over on the same day with the CRSP indexes,” he added.

His colleague Alexander Poukchanski, director of index analytics, said the idea was based on how active managers trade. “The goal for these indexes should reflect what active managers actually do. It’s a philosophical change,” he said.

CRSP has also introduced a concept called “packeting” to reduce turnover. This allows a stock close to the cut-off between, say, mid- and small-caps to be partly included in each index, reducing the trading that would previously have ensued when the stock switched index.

Johnson said a range of benchmarks were adapting their methodology to either minimise the impact of trading or, “to borrow the author’s term, ‘camouflage’ their trades”.

Li believed it was worthwhile for investors to search for ETFs that minimised the drag from trading. “I believe that investors who put money in low-turnover ETFs can achieve lower index rebalance costs [and] the cost savings could be as large as the management fees,” which average 15.1bp for US equity ETFs, he said.

[ad_2]

Source link