[ad_1]

All serious investors should pause at least once a year to admit their mistakes. Normally, we learn more from our failures than our successes. So, though painful, this reflection should help us refine our approach and identify whether we need to change it.

This year I am struggling to get my head around what has happened, simply because things have been so weird. Global equities have risen 21 per cent in sterling to date. This is after 13 per cent growth last year (with a big wobble in the spring). This adds up to 84 per cent gains over five years and 238 per cent since the low in February 2009. Anyone would think we had enjoyed an economic boom!

At university I read the classic text by US economist Paul Samuelson, Foundations of Economic Analysis. He taught that a rise in inflation sees bond yields follow in tandem. In the US, CPI inflation rose from 1.2 per cent in October last year to 6.2 per cent this October. US 10-year conventional bond yields were 0.8 per cent a year ago. They are now 1.4 per cent. They should have risen 5 percentage points, not 0.6, according to Samuelson. This is not normal and I hesitate to call it a new normal.

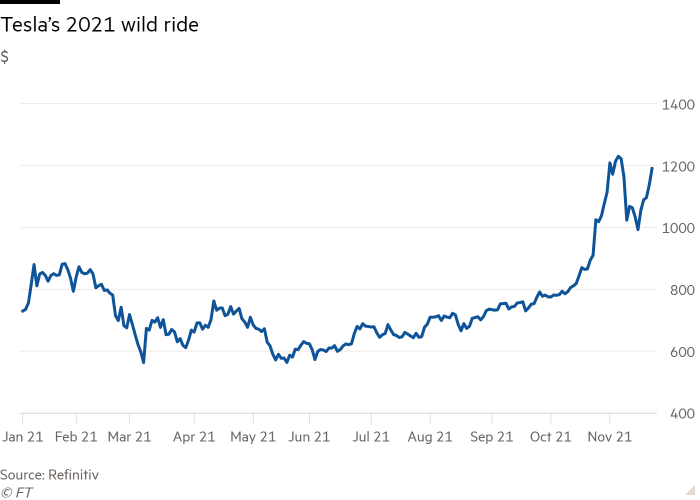

Equity markets have behaved weirdly too. My biggest failing this year has been not buying weird stocks. Some have risen a lot. Take Tesla, which is up 44 per cent this year. It is on course to generate just under $10bn in income in 2022, yet it is valued at more than 100 times that, at $1.09tn. That is a weird valuation.

We applaud Tesla’s development, but suspect its competition is about to get tougher. Not everyone can afford the £43,000 entry price. Long-established rivals are rapidly expanding their electric car ranges and competition from unusual directions is imminent. For instance, China’s Great Wall Motors will start selling its Ora Cat five-door hatchback next year, for about £25,000.

In our view, Tesla is a perfectly sensible company to invest in — just not at this valuation. However, it cannot compare in the weird stakes with Rivian Automotive, whose IPO was recently backed by Amazon and Ford. It is currently valued at close to $100bn — more than Ford or General Motors. It only began delivering its first trucks in October. It has zero revenues.

In the old days, such companies would be privately held and come to the stock market only when they could demonstrate success.

Hunter S Thompson, the US journalist and author, once said: “When the going turns weird, the weird turn pro.” Some investors who have backed such odd stocks have decided to offer their services as long-term savings managers, on the basis that they “get it” and others don’t. What could possibly go wrong?

Time to change tactics?

My funds, which in most years have beaten the MSCI global index, have struggled in 2021, lagging behind by about 1 per cent. So am I getting too old for this game? Are the youngsters who claim to get it the ones to follow?

Perhaps, but experience screams that starting to buy weird stocks now would be a mistake. Better to carry on trying to reduce the number of old-fashioned investments we get wrong. This year’s disappointments in this regard include some surprises.

Our worst investments have been in automation stocks, which dominate the Japanese portion of our portfolio. They performed well in 2020 and order books were generally strong coming into 2021.

Unfortunately, supply chain issues and the slowing Chinese economy prevented those orders coming through to sales and profits. However, if 2022 sees more progress towards normal trading conditions, we would expect greater demand for automation. We have taken the opportunity to add some investments, such as US sensor specialist Cognex, alongside our core Keyence holding.

Ørsted, the Danish energy group, is perhaps the most ironic disappointment. While world leaders gathered in Glasgow for the COP26 summit, we found ourselves selling the last of our shares in the wind farm specialist. As often happens, when governments prioritise an area such as renewable energy, the cheap loans they offer allow all comers to compete. Some did not need the incentive. The sight of big oil companies piling into the offshore wind industry to reposition themselves as climate change cherubs left me caught between laughing and crying.

Renewable energy capacity will be increased, which is great, but all these new players will drive down shareholder returns. Samuelson devotes several pages to the phenomenon, known as “crowding out”.

2022 rate rises will challenge equity valuations

Investors have done well over the past 10 years simply by buying companies whose products are selling well. There has been very little inflation, so cost issues have seldom arisen to challenge profitability. Valuation discipline has often got in the way of a good story.

This may not continue. Scarcities in many supply chains and areas of the labour market are leading to rising prices. Many companies will see their profits squeezed — something they and market analysts are out of the habit of predicting.

Higher environmental standards will also cause inflation — for many years to come. Wind electricity is still more expensive than burning coal in many parts of the world, especially where fossil fuel infrastructure is already in place and you have to factor in the costs of new plant for green energy.

China’s massive share of global coal-burning shows that its exports are effectively subsidised by pollution. This will not be acceptable, and higher tariffs on steel and the like are inevitable. Joe Biden, the US president, may end up with a similar China policy to Trump’s, though for different reasons. This will affect the price of traded goods. Meanwhile Chinese ports are raising tariffs by 10 per cent and more. It is difficult to see where or when inflation will peak.

Interest rates have been kept low, perhaps on the assumption that current inflation trends are transitory. But central banks are in a difficult position. German retirees, who mainly save in bonds — today yielding pretty much nichts — won’t tolerate 6 per cent inflation for long.

So 2022 will see a much greater likelihood of rate rises than recently anticipated — and that will be against a background of a rather anaemic economic recovery, not helped by the new Covid variant. I think it may well be enough to bring a recession in Europe in 2022, though probably not in the US.

A more positive scenario is that central banks allow yields to rise gradually towards inflation levels. If this happens, growth companies should be able to outpace that downward pressure on equity valuations, as long as they are not trading on questionable valuations to start with.

So what lessons have we learnt? Putting to one side the biggest losers and winners in my portfolio, I cannot help noticing how much of the gains have come from a long list of reliable, very profitable companies that seem to make steady progress year after year: Microsoft, Google, Thermo Fisher, Louis Vuitton and Mastercard. Good companies make good returns and invest for the future. However good you think they are, they often turn out to be better than you expect.

Simon Edelsten is co-manager of the Artemis Global Select Fund and the Mid Wynd International Investment Trust

[ad_2]

Source link