[ad_1]

Will 2022 be a year of risk or reward? There will be good investment opportunities in the markets next year but they will be balanced against the danger of shocks, as policymakers grapple with the pandemic, inflation, and climate change — as well as the Ukraine crisis and profound upheaval in China.

That’s the view of a panel of investment experts brought together by FT Money this week to debate the possible twists and turns of the financial markets over the next 12 months.

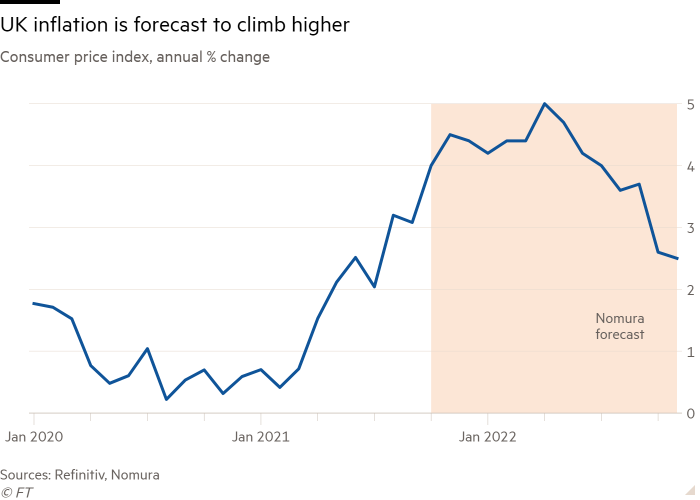

With the global recovery from the 2020 recession now well in train, they expect further economic growth next year. But they worry a lot about inflation. If policymakers clamp down too hard, they could threaten the recovery. If they go too gently, price increases could escape out of control and require more drastic action later.

“It’s a catch-22,” says Salman Ahmed, global head of strategic asset allocation at Fidelity International. He expects central banks will focus more on keeping borrowing costs low, so that servicing the world’s huge debts remains sustainable. He says: “The road to that can create a lot of downside risk if the market starts questioning the inflation credibility of the key central banks.” Meaning there could be a sharp sell-off in stocks and bonds.

But, says Ahmed, there is an “upside risk” that investors will avoid this fate because a continuing flow of easy money from the central banks will keep liquidity pouring into the markets. “That will then push everybody to buy equities . . . because you have nothing else to buy.”

Ahmed is cautiously optimistic that next year these forces will play out in a fairly benign way, with inflation perhaps settling at about 3 per cent.

For Merryn Somerset Webb, the FT Money columnist, this is altogether too rosy. It’s “very complacent” to assume that policymakers can somehow manage to keep inflation at about 3 per cent and the economy growing, she says. “Wouldn’t it be wonderful? We’ll gradually erode the debt and everything will be absolutely fine. But it seems incredibly unlikely to me.”

Somerset Webb says that with labour shortages and supply bottlenecks it’s “not that outrageous” to predict double-digit inflation “for a short period, maybe even for a lengthy period. And I’m pretty sure that central banks aren’t prepared for that.”

She adds, somewhat provocatively, that perhaps the low inflation of recent years has “absolutely nothing to do with central banks” but was driven by economic changes — globalisation and the rise of China — which reduced labour costs. “We may now be entering a different period of higher inflation which, again, central banks will have absolutely no control over.”

Somerset Webb and Ahmed joined a panel that included two other fund managers — Anna Macdonald of Amati Global Investors and Simon Edelsten of Artemis Fund Managers — plus Gavin Jackson, the FT’s economics editorial writer.

We met over sandwiches and mince pies at the FT’s London headquarters in Bracken House, unlike last year when our panel convened over a video link. This year, we got in just before the pandemic cast a new cloud over the outlook, with the UK government’s latest appeal to work from home.

Of course, all predictions are uncertain. But our panellists agreed that the pandemic makes forecasting even more difficult than usual, especially as it coincides with a sharp increase in political tensions. We talked about China and the threat it poses to Taiwan, Russia’s belligerent approach to its neighbours, and the Middle East.

The return of geopolitical risk?

Macdonald says that from an investment point of view the biggest geopolitical issue is China-Taiwan, with so much of the global semiconductor industry based in Taiwan. “That would be a significant issue and I’m not clear about how we would all respond to it.”

But, reflecting widely held views in markets, she adds: “I don’t actually think that is as likely as [conflict between] Russia and Ukraine. Given what lies ahead for China this year [including containing Covid], I don’t think invading Taiwan is top of their list. I do think that Russia is possibly more unpredictable.”

Ahmed says: “I would agree with that assessment. China is the most important one for a long-term perspective. It’s a big market. It’s a huge economy, a complex economy, a different economic model.” But “given the recent history” including the occupation of Crimea in 2014, Russia “is a more volatile” country.

Ahmed adds that Russia’s “economic importance has reduced because of ongoing sanctions”. But because Russia is a big energy exporter, “we’ll have to watch oil obviously very, very closely. That’s the transmission channel to the rest of the world” — not least for Europe, which is dependent on Russian gas.

Jackson throws the Middle East into the mix, arguing that it was puzzling that Iran was no longer in the headlines when only two years ago it topped the geopolitical risk agenda. He says: “I guess I’m always surprised by how confident people are in the authorities’ ability to handle things.”

Inflation in Covid conditions

As befits financial specialists our panel mostly focus on money and the markets. They agree that the pandemic has created unprecedented conditions. Or as Edelsten puts it: “This is undoubtedly the weirdest equity market I’ve ever seen.”

Economics textbooks predict that when inflation rises so do bond yields. However, bond yields have barely moved, even though inflation has now increased in the US and Europe. As long as bond yields stay low, equities seem to be stable. But Edelsten says: “But equity markets can’t cope if that bond yield starts to move very quickly to the inflation level [which is currently around 3 percentage points higher]. Western equities will go down, though Asia has less inflation and may cope . . . The universal bullishness doesn’t necessarily fit very comfortably with some of these issues.”

Jackson adds that economic growth will slow since most of the pandemic recovery has already taken place, especially in the US and UK. “In the UK it will feel like a slowdown because we will also have tax rises coming in, we might have an interest rate rise and we will have higher prices.”

On top of that comes the fast-spreading Omicron variant of Covid-19. Jackson says: “I think it will be very hard for investors over the next year because with things like Omicron, we don’t really know what the impact will be yet on inflation. It could make it worse. So if you’ve got slower growth and potentially higher inflation, that puts everybody in a tough spot.”

Macdonald warns that supply shortages in China may persist, contributing to global inflationary pressures. The authorities are determined to fight Covid, including with lockdowns, especially with the Winter Olympics due early next year and the Communist Party Congress later. She says: “So they want a steady year. That can mean they will still try to be very draconian in shutting down any kind of outbreaks that they see, which will jam up supply chains.”

She adds: “In the past, I think if you had a single supply chain issue, you could perhaps model that it might take six months to resolve. But the problem now is that these [issues] are coming in lots and lots of different ways.”

Growth, value and energy stocks

So how to take account of inflation in choosing stocks? Edelsten counsels savers to focus on Asia, where there is “very, very little inflation”. He also recommends sectors which manage inflation well. Railways, for instance, where companies have proved adept at passing on price increases to consumers. He says: “They’ve been doing it for 100 years. In fact, they’re so good at it that generally they have to be regulated and told not to do so.”

Another winner could be robots, for their value in replacing workers during times of labour shortage. “Japanese robot manufacturers have got loads of orders,” he says.

For Somerset Webb a good option in inflationary times is value stocks, which she argues have long been neglected in favour of growth stocks such as tech companies. “It does come to a point when a cycle has to turn around.”

She particularly likes energy and mining stocks, arguing that these sectors have seen capital investment drop in recent years amid concerns about climate change. She says: “And that’s going to continue going forward as we have this kind of huge political drive towards net zero, et cetera. You know, politics is way ahead of practicalities, and that’s going to make a big difference to energy prices and to commodity prices.”

Even the green revolution requires metals and energy to produce the necessary new infrastructure. “You need a lot of stuff that we haven’t been investing in enough to make to get us to where we want to go.”

Macdonald agrees on the appeal of commodities, saying: “We do see a huge amount of opportunity in some of those [companies]”.

Edelsten argues it’s time to be more focused on value and valuation. He says: “For me when the macro fundamentals are getting worse, I just think one should be much, much more cautious about valuation and much more thorough about it. I have moved my fund from being very growth oriented to being more of a balance.”

Panellists still see opportunities in tech, but with a much greater focus on larger groups with reliable earnings. Ahmed says: “There is a big difference between profitable and unprofitable tech stocks.”

The next phase in tech investing

Edelsten argues that established tech giants are seeing such large and increasing profits that they can reasonably be valued in the traditional way, in terms of a price/earnings ratio. He gives Alphabet, the owner of Google, as an example. “I think it’s on 26 times earnings next year . . . it’s got a normal valuation. It’s a very stable, incredibly profitable business. Be nice to have a yield at some point.”

But at the other end of the spectrum are “the very young tech companies correlated” with electric carmaker Tesla, which has seen stratospheric stock market performance. “So there are bits of the American equity market which look very, very dangerously valued indeed. That bit of tech will have a difficult time, a very difficult year,” Edelsten says.

Could a Tesla stock market plunge trigger a wider sell-off? The question divided panellists. Edelsten says not. He argues that the investors backing Tesla, and the investment banks behind some of them, are a “subset” of the market. “It’s one particular group of people who talk to each other. It’s not a mainstream game . . . There could be some very nasty losses. I’m sure that it would cause some headlines, but I don’t think it’s going to be a crisis.”

Jackson is not convinced, pointing out that as Tesla has entered important indices including the S&P 500, many index tracker funds are obliged to hold the shares. And there is little way of knowing, until it is too late, how much investment in Tesla is on credit. He says: “There is hidden leverage, you only see it when markets are going down. If the fifth biggest company [by market capitalisation] in the world takes a tumble, there will be knock-on effects.”

Ahmed warns more generally about the level of US debt, with debt held by the public soaring as a share of GDP from about 40 per cent in 2007 to 100 per cent this year. A sharp rise in interest rates of 200 or 300 basis points would be “a shock . . . the system would collapse”.

He adds that some of the strength of the US economy is due to people spending money poured out in the huge fiscal stimulus launched to counter the pandemic’s effects. “Frankly speaking, equity markets have a lot to thank the government [for] because a lot of those earnings are actually fiscal stimulus being recycled. The stimulus will be shut down ultimately and growth will need a new engine.”

Edelsten is more optimistic about the US, pointing to strong growth and the solid finances of large American companies. “I am really quite positive about large companies, even in the grim moments of discussing the collapse of the system, because all the big companies have got massive amounts of cash on the balance sheet.”

What are the prospects for the UK?

And how about the UK market? Edelsten, who generally looks for growth-orientated companies around the world, says: “Trying to find growth stocks in the UK is really hard.”

Somerset Webb takes a quite different view. She delights in saying that retail savers can profit from global fund managers’ neglect of the UK. “I still think that the UK market is something of a gift from the international institutional investor to the retail investor.”

She says institutions tend to think the British market has “got the wrong sector mix, that Brexit still isn’t quite dealt with, that it’s got all these nasty, dirty companies [in oil and gas, for example] that people don’t really want to be involved in”.

The net result is that “it’s still extremely cheap relative to most global markets”, says Somerset Webb.

Macdonald, a UK specialist investor, is less sweeping, but argues that “there’s lots of small and mid-cap stocks that offer tremendous amounts of growth”.

She likes businesses which can profit from the transition from traditional commerce to online. A favourite in her portfolio is Accesso Technologies, a company that offers virtual ticketing services to theme parks and theatres. Another is Auction Technology Group, publisher of the Antiques Trade Gazette newspaper, which has successfully developed online auctions such as saleroom.com.

Macdonald says some companies she has bought in initial public offerings have grown to “pretty substantial companies” with market capitalisations of £1bn or more.

But investors should be selective in sifting through shares and searching for their dream stocks. As Macdonald says: “You do have to kiss an awful lot of frogs.”

[ad_2]

Source link