[ad_1]

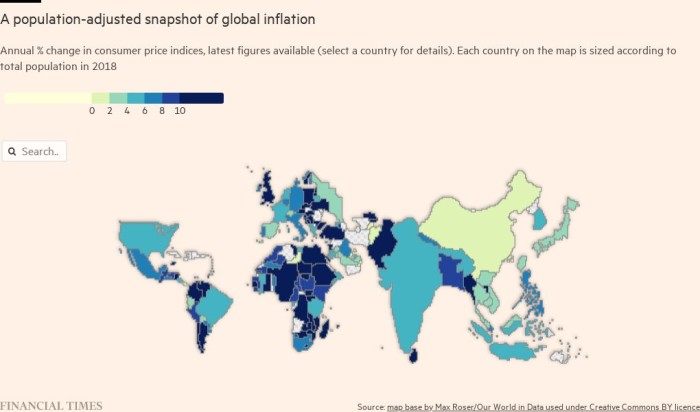

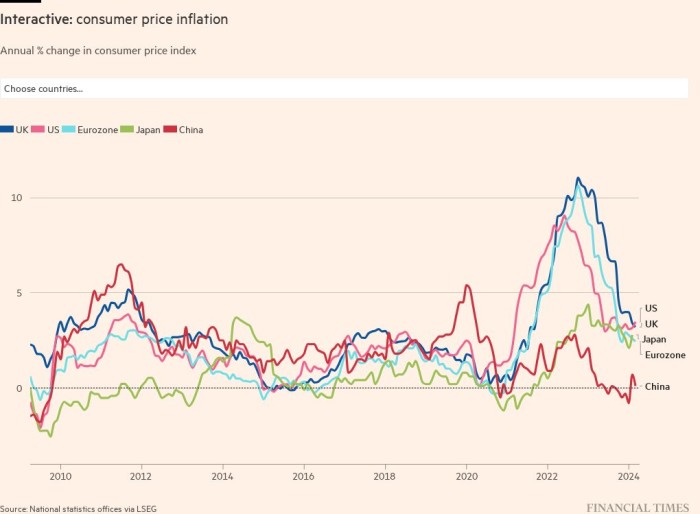

Much of the world is experiencing a dramatic bout of inflation. Yet many central banks are keeping interest rates at or close to record lows, despite the rise in prices caused by higher energy costs, strong consumer demand and the disruption to global supply chains wrought by coronavirus and its latest variants. House prices have also soared.

Some fear a general return to the chronic inflation of the 1970s. The one exception to the worldwide pattern of rising consumer prices are East Asian countries such as China and Japan. But even here, there are signs that inflation is starting to rise.

This page provides a regularly updated visual narrative of consumer price inflation around the world, both now and for next year. It separates inflation into its main components: what higher food prices mean for consumers; and where investors think inflation is heading over the medium term. It also tracks house prices.

One of the points of debate among policymakers and economists is whether the rise in consumer prices is transitory and will fade soon, or whether it may prove more permanent.

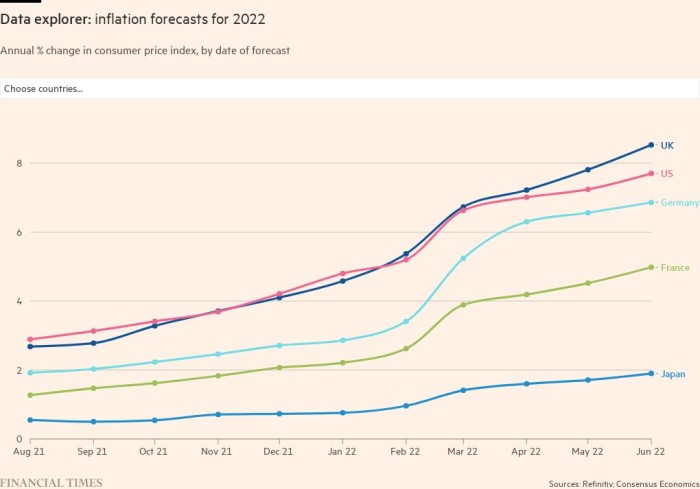

Yet even among those who believe that inflation will fall next year, there is an acceptance that the inflationary shock will last longer than first estimated. Economists polled by Consensus Economics, a company that collates the predictions of leading forecasters, have steadily revised up their expected inflation figures for 2022.

Another point of concern is asset prices, especially houses. These have soared in many countries during the pandemic, boosted by ultra loose monetary policy, homeworkers’ desire for more space, and government income support schemes.

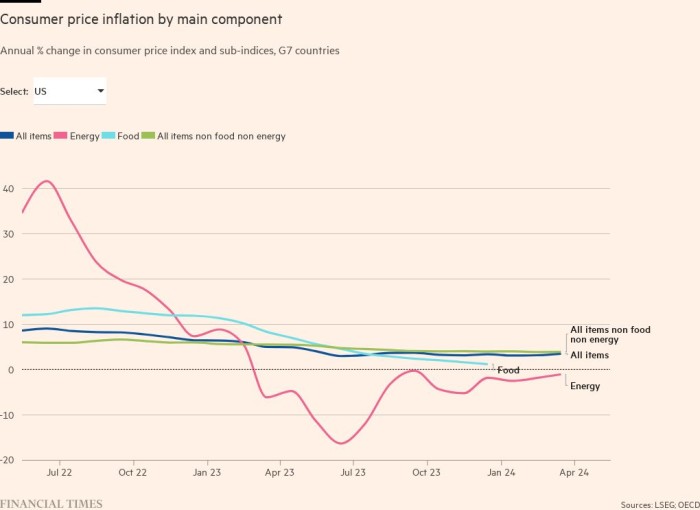

Rising consumer price inflation is a challenge for central banks, not least those G7 countries that have a price stability target of 2 per cent. To reach that goal, central banks can adjust monetary policy to curb demand. But such tools are less effective in tackling inflation created by lack of supply. As the governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, has said, monetary policy “doesn’t get more gas, more computer chips, more lorry drivers”.

The rise in energy prices, which has driven inflation in many countries, is a case in point. In one sign that inflation may be spreading beyond energy, the price of many other items is also increasing — especially in countries where consumer demand is strong enough for businesses to pass on higher costs.

Rising prices limit what households can spend on goods and services. For the less well-off, that could lead to their being unable to afford basic needs, such as food and shelter.

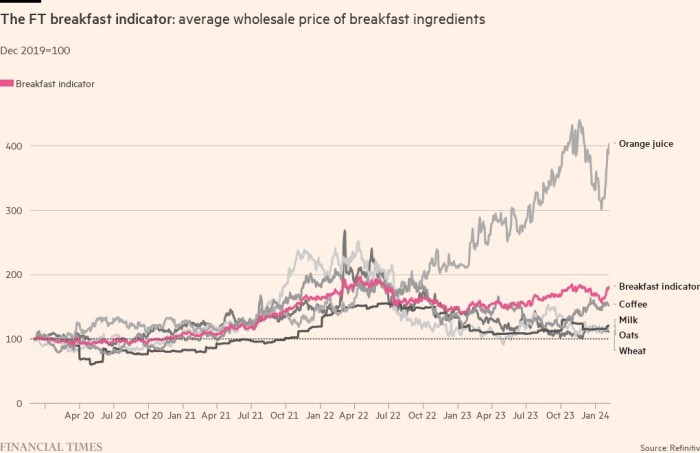

Daily data on staple goods, such as the wholesale price of breakfast ingredients, provide an up-to-date indicator of the pressures faced by consumers. In developing countries, the wholesale cost of these ingredients has a larger impact on final food prices; food also accounts for a larger share of household spending.

The debate over whether the surge in inflation is temporary or more permanent continues. Supporters of “team transitory” believe the price spikes are due to a one-off surge in consumer demand bumping against a one-off rise in supply chain disruptions. Supporters of “team permanent” point to a broadening pattern of price rises, especially in countries where a shortage of workers is pushing up wages.

Markets generally seem to have sided with “team permanent” and, in many countries, have steadily priced in a rise in inflation over the next five years.

[ad_2]

Source link