[ad_1]

Large funding deficits are driving pension plans to plough money into private assets in pursuit of returns, heightening the risk of crowded trades and subdued gains, according to new research.

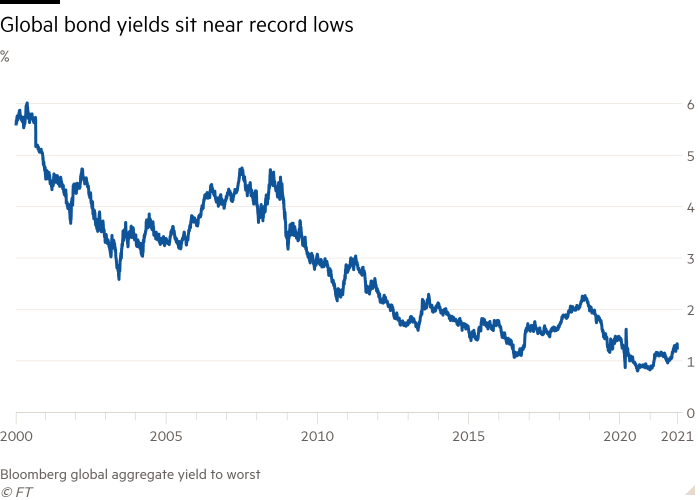

The report by Amundi, Europe’s largest asset manager, and Create Research surveyed 152 defined benefit pension plans managing €2.1tn in assets. Its findings illustrate the scale of the challenges facing the global pensions industry as it seeks to escape the punishing effect of historically low bond yields along with elevated valuations across equities markets.

Funds have been buoyed since the 2008-09 financial crisis by a powerful rally in equities markets that has helped to counteract the lacklustre streams of interest payments that are provided by holding government or corporate debt. But many managers now worry about growing headwinds: just over seven out 10 respondents in the poll say they are expecting returns to be significantly lower in the years to come.

“This was not how the endgame of defined benefit plans was meant to play out,” said Amin Rajan, chief executive of Create Research. “Three things conspired against them: low interest rates, ageing demographics and an immediate need for cash flow at a time of low interest rates.”

Defined benefit pension plans, which promise a guaranteed retirement income that rises along with inflation, have traditionally been steered by regulators to hold assets that match their liability flows, such as bonds.

The problem has been compounded in recent months by a surge in price growth across the world that has made it difficult to find highly rated bonds that provide positive returns after accounting for inflation.

The low-rate environment is forcing pension managers to hunt for returns in other markets, particularly in unlisted assets.

Rajan estimates that defined benefit schemes have increased their allocation to private assets from five per cent 15 years ago to around 20 per cent today. They are continuing to increase their private allocations, lured by the prospect of capital growth, income and protection against inflation, he said.

Holdings of private assets — which includes private debt, private equity, real estate and infrastructure — are expected to rise 60 per cent between 2020 and 2025, to surpass $17tn in assets under management, according to data provider Preqin.

However, Rajan cautioned that as managers rush into private assets they faced greater competition, including from the world’s biggest pension funds, and risked overpaying for assets.

“Private assets are a high dispersion space, meaning that there is a big difference between the best and worst managers. This means that manager selection is vital,” he said. “Although money is pouring into the private market there is no guarantee it is going to deliver big returns. At the moment the opportunity set is limited.”

It is also often more difficult and expensive for investors to buy, sell and evaluate private investments since they do not trade on public markets.

About 75 per cent of pension funds who responded to the survey said they were pursuing low-risk strategies before the pandemic. Of that cohort, around a third were now redeploying capital in the search of higher returns.

“Going into risky assets is not the best option for some plans but it is, unfortunately, their only option,” said Pascal Blanqué, group chief investment officer at Amundi.

Earlier this month the board of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the largest pension fund in the US, voted to use borrowed money and alternative assets to help it to meet its target for investment returns. In July, the C$221bn Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan unveiled plans for a fresh C$70bn push into private markets, spanning assets from infrastructure to real estate.

[ad_2]

Source link