[ad_1]

Record high house prices in the UK, Germany, the US, New Zealand, Australia and Canada have one thing in common: historically low interest rates that pushed down the cost of mortgages, supporting demand. Yet rates are expected to rise by the end of next year in most countries, and when they do they could shake what has underpinned the fastest annual real house price growth in the OECD countries in many decades in the first quarter of 2021.

In the UK, the Bank of England unexpectedly kept interest rates at the current historical record low of 0.1 per cent in November, but markets expect a hike at the December Monetary Policy Committee meeting with further rises likely next year.

Will house prices tank as a result? The answer depends on the size and timing of rate increases, experts say, as well as on how much a shortage of properties and a strong labour market continue to apply upward pressure. Forecasts vary from a slowdown in growth to an outright contraction.

The UK official house price index grew at an annual rate of 10.6 per cent in August, a near-record pace since 2007, despite fears of a sharp correction after the reduction of the stamp duty discount in July. In October, the Nationwide house price index showed that the trend continued even after the return to pre-pandemic stamp duty rates.

Lucy Pendleton, property expert at estate agent James Pendleton, says this was the result of buyers rushing ahead of “a near-certain string of interest rate rises” expected over the next 18 months that is proving to be “a far more powerful motivation to transact than the stamp duty holiday ever was”.

Boris Glass, senior economist at S&P Global Ratings, says “any hike would translate into higher costs for would-be buyers and thus lower demand, while putting downward pressure on house prices.”

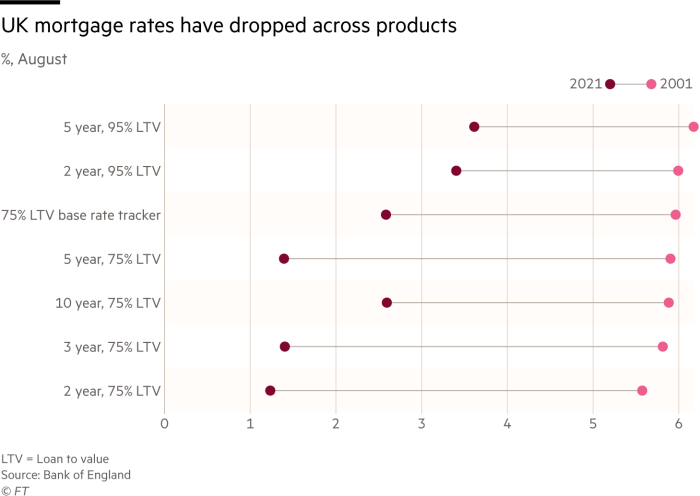

In anticipation of the hike, many mortgage lenders have already increased their mortgage rates over the past few weeks.

Jeremy Leaf, a north London estate agent, says that although a rise in interest rates would directly impact only a small proportion of borrowers on variable-rate deals, a rise would compromise confidence in the wider market, particularly among first-time buyers on tight budgets.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, the UK fiscal watchdog, in its outlook published with last month’s Budget, forecast that mortgage interest payments would rise by 20 per cent in the two years to Q3 2023, the fastest increase in more than a decade.

Martijn van der Heijden, chief finance officer at the mortgage broker Habito, says that even if the rate increases by as little as 0.25 per cent, many could see their repayments shoot up by hundreds of pounds a year.

More than 3.5m first-time buyer mortgages have been issued since the Bank of England dropped its policy rate to 0.5 per cent in 2009, following sharp successive cuts from 5.75 per cent in 2007. “That is a large group of homeowners who don’t know what it’s like when interest payments rise meaningfully,” says Tom Bill, head of UK residential research at Knight Frank.

However, interest rates have a long way to go even to reach historical averages following last year’s rate cut to 0.1 per cent, the lowest since the Bank of England was created in 1694. Similarly, mortgage rates are hovering at near-record lows. In September the average “effective” interest rate — the actual interest rate paid — on newly drawn mortgages was 1.78 per cent, down from a 15-year peak of 6.2 per cent in 2008. Over the same period it fell from nearly 6 per cent to 2 per cent on outstanding mortgages, the lowest on record, according to Bank of England data.

Banks could absorb some of the increase in financing costs in their margins, reducing the increase in mortgage rates, experts say. Other factors could mitigate softening demand as a result of rising rates: the labour market is solid, with businesses often increasing wages to attract and retain staff; and UK households have accumulated savings equivalent to nearly 9 per cent of GDP since the first Covid-19 restrictions, according to Bank of England data. “These savings are concentrated mainly in middle and higher-income households, which are exactly those who were able to buy [houses],” says Glass.

At the same time, there are few houses for sale, according to the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, with surveyors reporting near record-low available houses available for sales per branch across all regions in England and Wales.

However, other factors point to weakening house price growth.

Property prices relative to income for first-time buyers are now at a historical high, according to Nationwide. In London, it can take 16 years for someone on an average wage to set aside a 20 per cent deposit for a typical first-time property, according to calculations by Nationwide.

“We anticipate rate rises will slow house price growth, particularly in areas where affordability is already very stretched such as London,” says Lawrence Bowles, senior research analyst at Savills.

Overall, this means a large variety in forecasts. Nitesh Patel, strategic economist at Yorkshire Building Society, says YBS expects house prices to continue to increase “but at a slightly slower rate next year”.

Glass thinks that the UK house price growth is already experiencing a soft landing and “if hikes come too soon or are too big, it might hit the housing market in the middle of that adjustment phase and exacerbate it”.

“We think the rise in mortgage rates looks set to be abrupt enough to mean that house prices stagnate in the first half of 2022,” is Tomb’s verdict.

A bank rate increase to 0.75 per cent could result in house price growth slowing to 4 per cent by the end of 2023, according to Andrew Wishart, property economist at Capital Economics. But “if the MPC undertakes a significant tightening cycle, perhaps raising bank rate to 1.5 per cent, house prices could drop by 4 per cent.”

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first

[ad_2]

Source link